On this date 75 years ago, the world's first atomic weapon was detonated in a test in New Mexico. The intent was to prove that the bomb — the product of an $1.89 trillion project —would work. Three weeks later, two atomic bombs would be dropped on Japan, at great cost of civilian lives but ending World War II without a potentially even more costly invasion of that country.

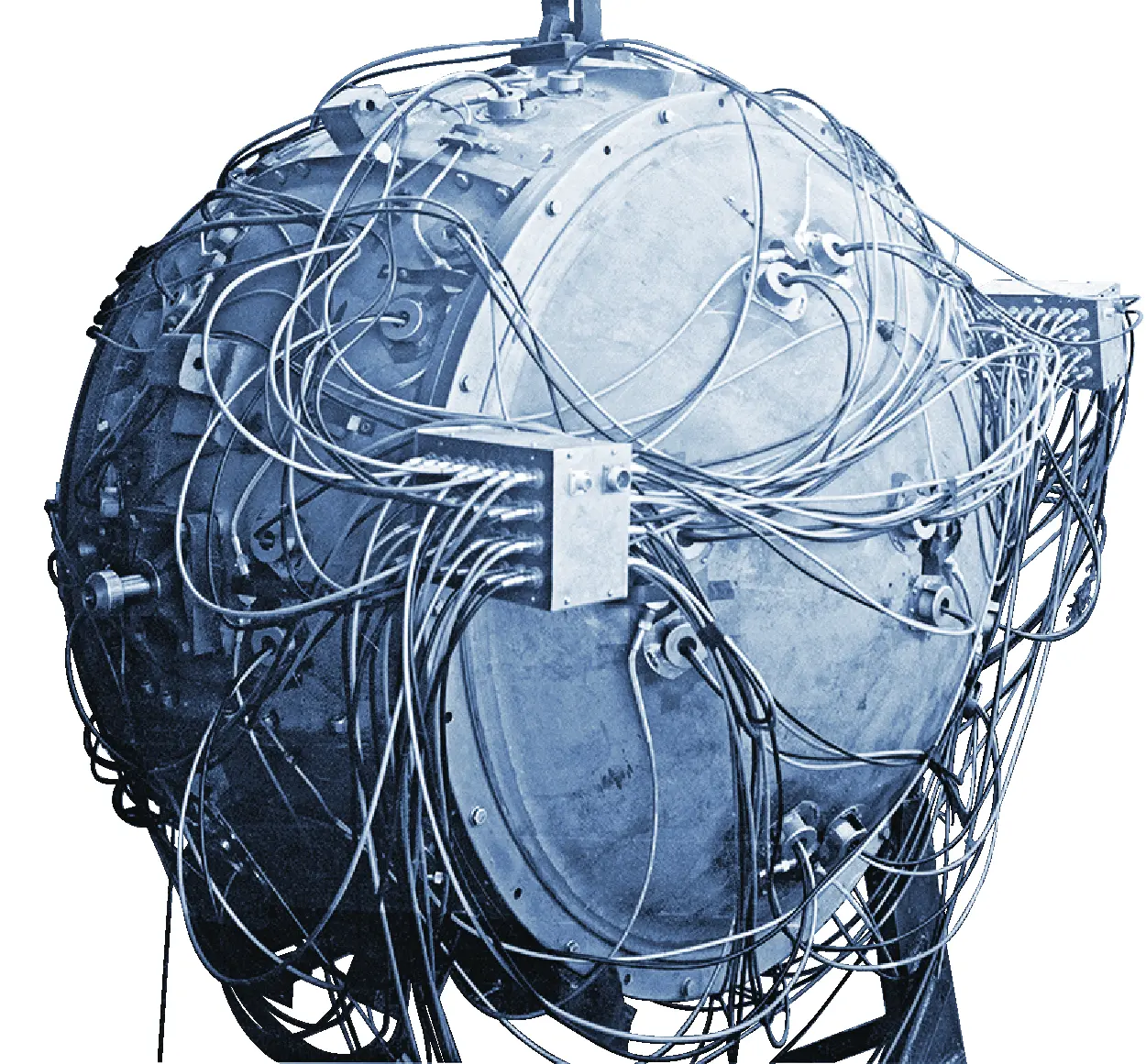

'The Gadget'

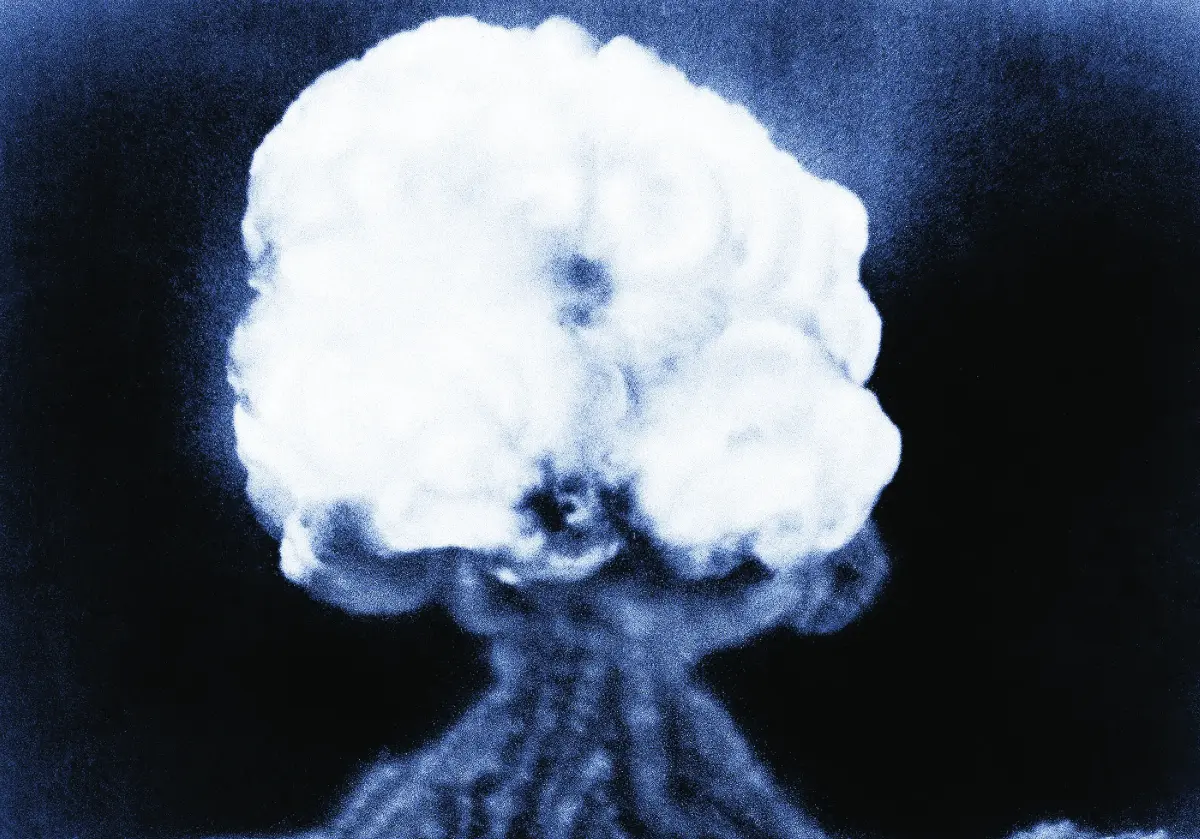

The first test atomic explosion in New Mexico on July 16, 1945, created a mushroom cloud 7½ miles high and a crater a half-mile wide and 10 feet deep. The sand within the crater had been boiled into a highly radioactive jade green glassy crust.

The Manhattan Project

With war on the horizon in Europe in early 1939, German refugee and physicist Leo Szilárd and two Hungarian-born colleagues, Eugene Wigner and Edward Teller, realized if Germany annexed Belgium, this would give Germany access to the world's largest supply of uranium in the Belgian colony of Congo.

Worried that the Nazis could pursue building an atomic bomb — such a bomb was purely theory at that point — Szilárd, Wigner and Teller enlisted the help of yet another colleague: the most famous scientist in the world, Albert Einstein of Princeton University. Grasping the significance of a bomb powered by a nuclear chain reaction, Einstein gasped: “I never thought of that!”

Einstein dictated a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt to be delivered via a mutual friend, economist Alexander Sachs.

Roosevelt, too, grasped the importance of what the Germans were potentially up to. He formed an advisory committee which led to the creation of the top-secret Manhattan Project in October 1941.

Major General Leslie Groves — who had just finished overseeing the building of the Pentagon — was put in charge of the project. Theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer of the University of Chicago was given the task of leading the scientists who would work out the details of the new weapon.

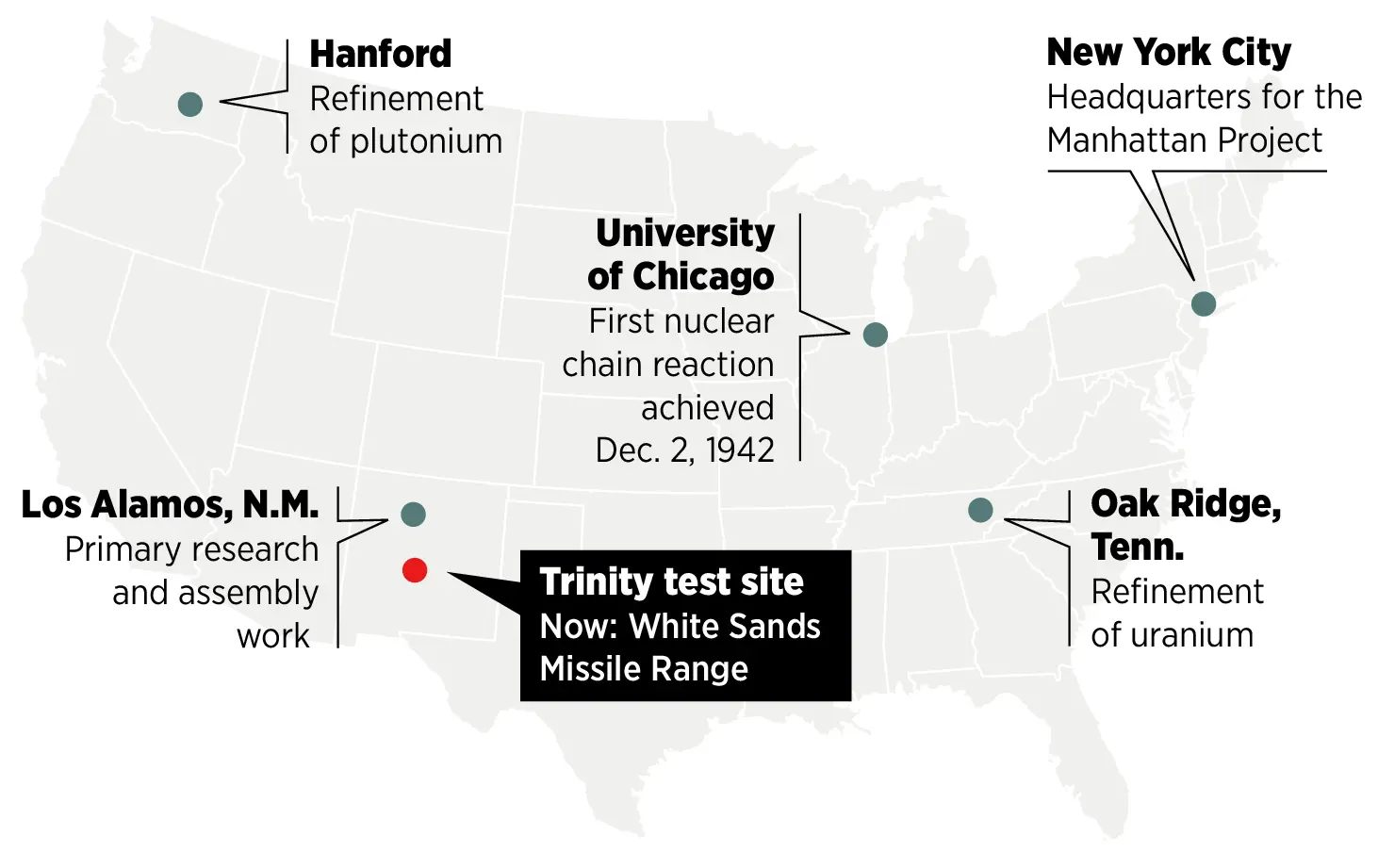

Work for the Manhattan Project would occupy several sites across the U.S. as well as a few in Canada. Here were some of the most notable:

The Manhattan Project was so secret that Vice President Harry Truman had to be pulled aside when President Franklin Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, and briefed on the atomic bomb project and what it could potentially do. Truman wrote in his diary that night that the U.S. was building an explosive great enough to destroy the whole world.

How The Bombs Worked

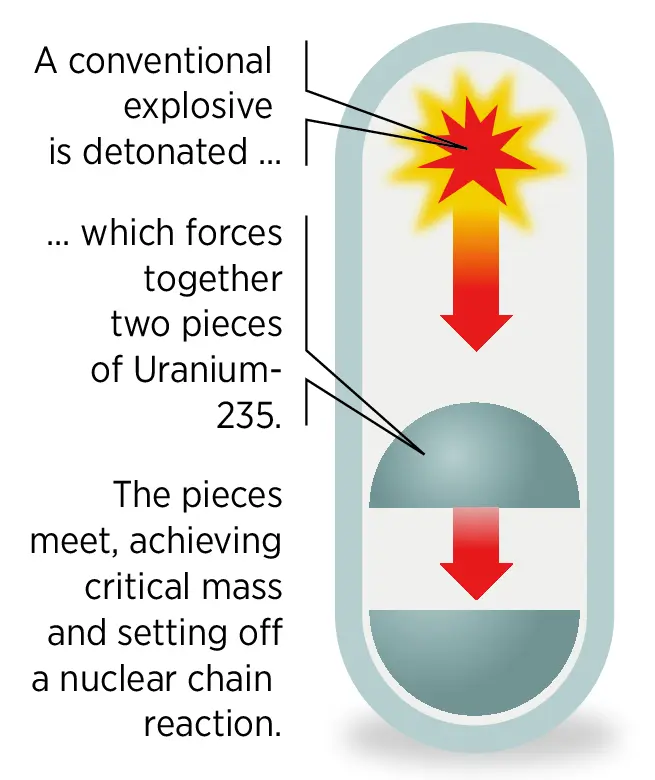

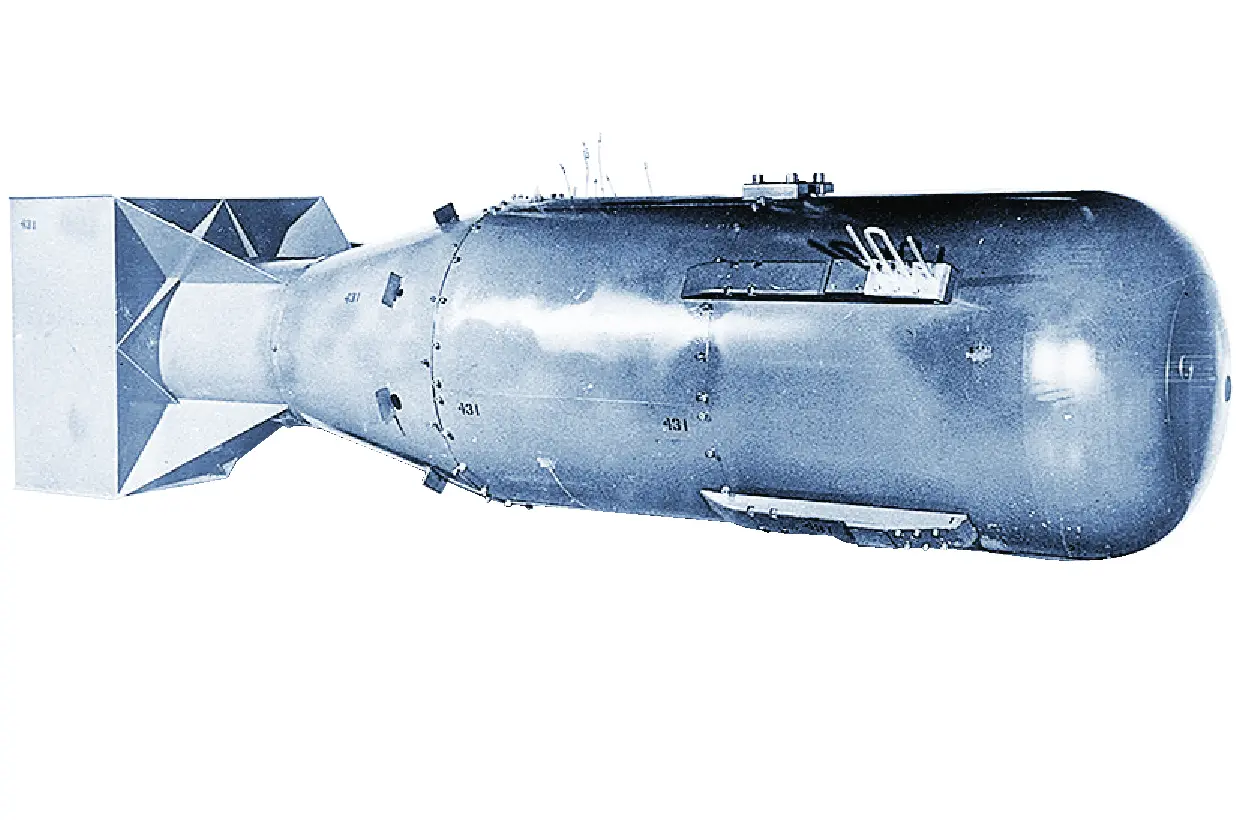

The scientists at Los Alamos built two types of bombs. The first was a more simple gun-like device:

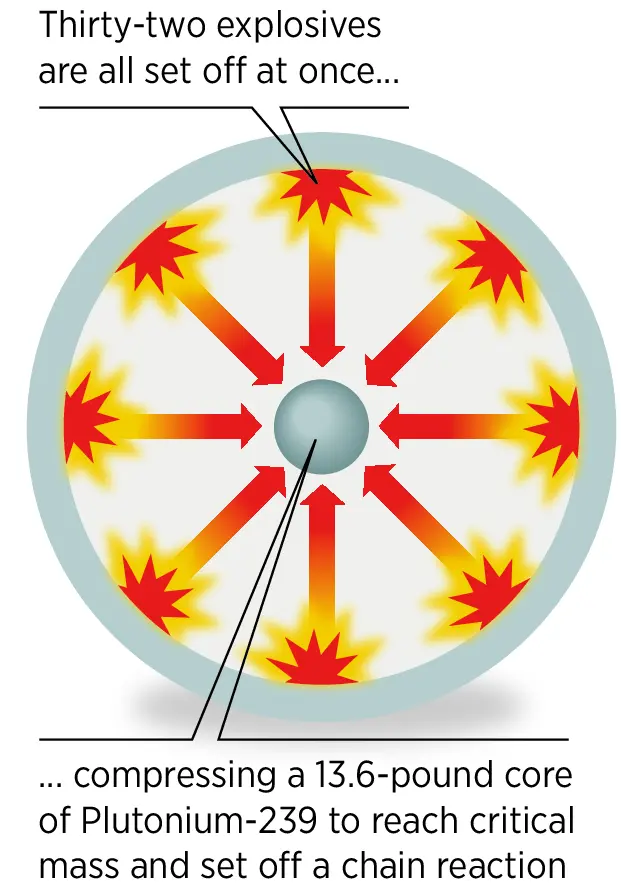

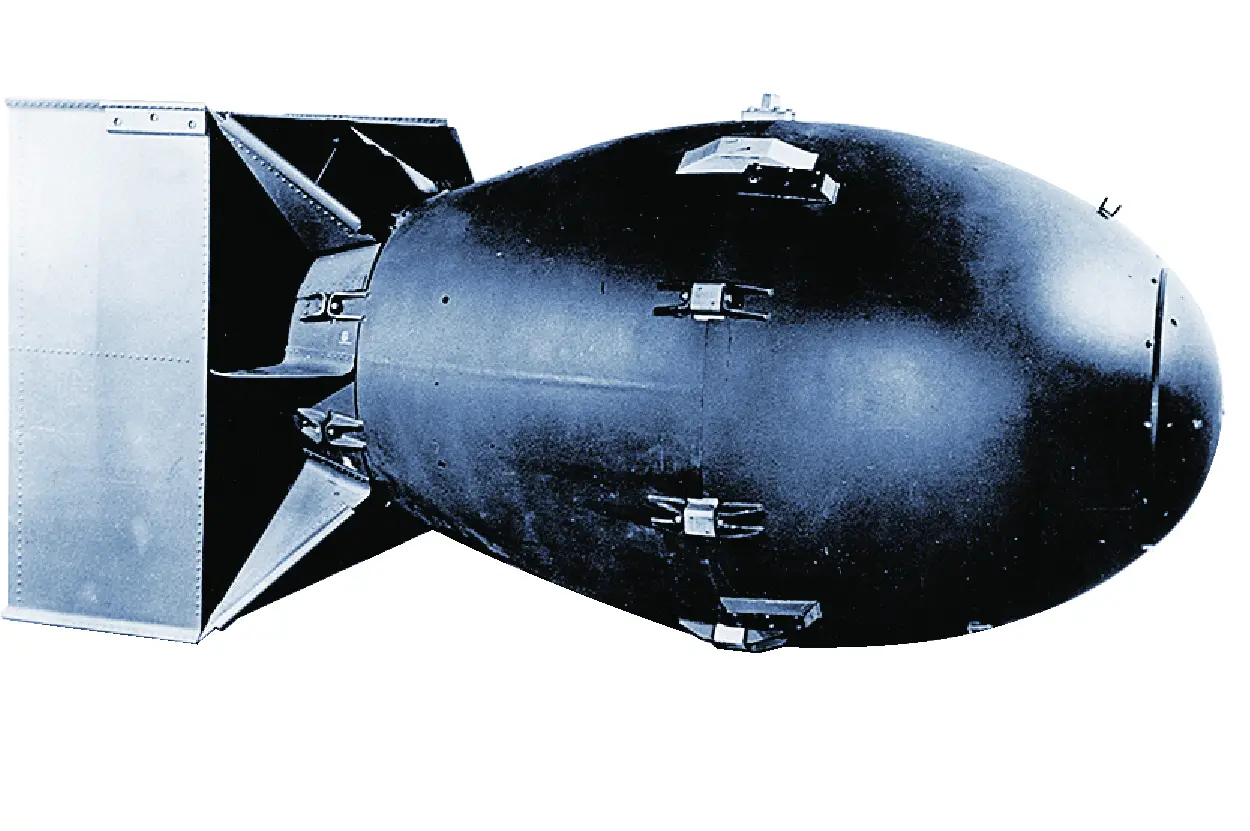

The second type was a more complex implosion method:

Oppenheimer's team knew this second method could yield larger results. But they needed to test it first.

The Cast of Characters

"The Gadget"

- Core

- Plutonium-239

- Weight

- 4 tons

- Detonated

- At the top of a 100-foot-tall steel tower on a U.S. Army Air Force bombing and gunnery range about 35 missiles southeast of Socorro, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945

- Blast

- Equivalent to 20,000 tons of TNT

- Fatalities

- None

“Little Boy” and “Fat Man” would be the only two atomic bombs used in warfare. The team at Los Alamos expected to have another bomb ready in late August and then roughly one every other week after then.

"Little Boy"

- Core

- Uranium-235

- Weight

- 4.5 tons

- Detonated

- 1,890 feet over Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945

- Blast

- Equivalent to 16,000 tons of TNT

- Fatalities

- 68,000 or about 27% of the city's population. 76,000 were injured by the blast.

"Fat Man"

- Core

- Uranium-239

- Weight

- 5.1 tons

- Detonated

- 1,650 feet over Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945

- Blast

- Equivalent to 21,000 tons of TNT

- Fatalities

- 38,100 or about 22% of the city's population, 21,000 were injured by the blast.

The Trinity Test

As work progressed toward a working weapon, Oppenheimer's team insisted on a live test — especially of the complex Plutonium version of the bomb — to make sure it would work. Truman asked for a test to be conducted in time for the Allied summit conference in Potsdam, Germany.

So the day before the Potsdam conference was to begin, the Los Alamos team loaded its first working bomb — “the Gadget” onto a truck and hauled it to an Army Air Force bombing and artillery range near Socorro, New Mexico.

As the physicists made final preparations for the test, they made bets on how powerful the atomic blast would be. The good-natured wagering came to an end when Enrico Fermi — who had overseen the first nuclear reactor in Chicago in 1941 — was overhead taking side bets that the bomb would ignite the atmosphere itself and whether or not it would destroy just New Mexico or the entire world.

Clear weather was a must for the test. But after the bomb was hoisted atop a specially built 100-foot steel tower, a powerful thunderstorm broke loose. Eventually, the weather cleared and the planned 4 a.m. detonation was pushed back slightly. The weather cleared as forecast and “the Gadget” was triggered at 5:30 a.m. local time.

The blast was tremendous. It was heard more than 100 miles away and the pre-dawn flash was seen more than 250 miles away. The resulting mushroom cloud reached 7½ miles high.

Word of the successful test was sent via a coded message to Truman, in Potsdam. On July 24, Truman would issue the order to the Army Air Force to use the bomb against Japan. Which it did on Aug. 6 and again on Aug. 9.

This edition of Further Review was adapted for the web by Zak Curley.