Idaho Sen. Crapo quietly builds record, moves past DUI

Here's my full story from spokesman.com:

By Betsy Z. Russell

In nearly a quarter-century in Washington, D.C., Idaho Sen. Mike Crapo has quietly built a reputation as a diligent, hardworking conservative who plays by the rules, quickly rises to leadership positions and is willing to reach across the aisle to get big things done.

So his 2012 arrest for drunken drivingwas especially jarring – it didn’t fit the image of the teetotaling, Mormon senator, a Harvard-educated attorney known for his quiet advocacy on health, tax and budget issues.

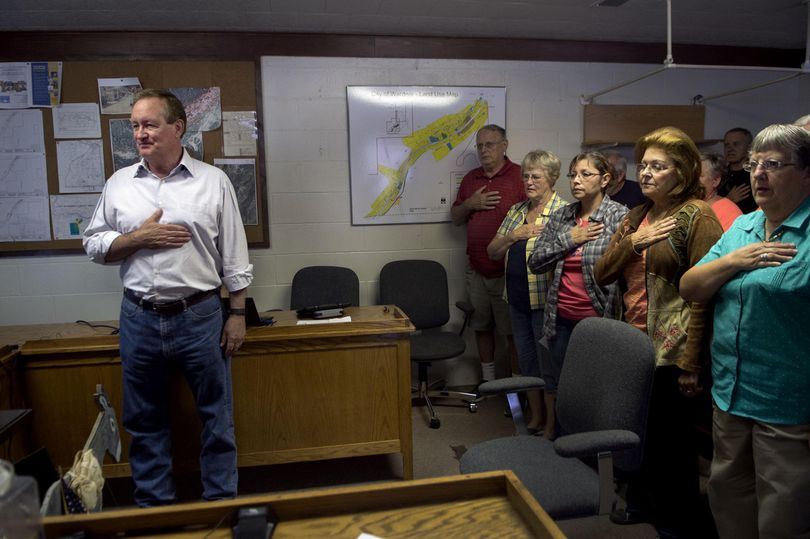

Crapo has labored in the shadow of a beloved older brother and successful Idaho politician who died young of cancer; fought a tough fight following his own cancer diagnosis while serving in the Senate; and weathered the DUI scandal with low-key apologies, a pledge to swear off alcohol and dogged work. When he held a record 200 town hall meetings across Idaho over the past two years, no one asked him about it.

Crapo’s biggest splash in Washington, D.C., came when he served on the Simpson-Bowles Commission and the bipartisan “Gang of Six” senators pushing a big, tough plan to cut the national debt by both cutting spending and raising revenues – a plan that included reforming the tax code, lowering tax rates while eliminating loopholes and reforming entitlements like Medicare and Social Security. He’s not often been in the national news since, aside from the DUI.

But in his most recent six-year term in the Senate – his third – Crapo sponsored seven major bipartisan bills that became law. They included the Indian Trust Asset Reform Act, which passed this year, and a significant change in how fine and penalty funds are distributed to crime victims, which resulted in an increase in funds to victims from $500 million in 2015 to $3 billion in 2016. He has more bipartisan initiatives in the works on nuclear licensing, which could benefit the Idaho National Laboratory, and funding for fighting wildfires.

“My style, my approach is to build bipartisan solutions and support,” Crapo said. It’s the only way, he said, to get anything passed in the Senate, where a 60-vote majority is required in the 100-member body.

“So you have to get past the partisanship,” he said. “But you have to do so in a way that does not yield your principles.”

Crapo has long been known as the opposite of a back-bench bomb-thrower. His landmark Owhyee Initiative legislation in 2009 brought together ranchers, recreationists, conservationists, county commissioners and others to resolve land-management issues and designate a new wilderness in southern Idaho. After eight years of work on the project, he became an outspoken advocate for collaboration.

But his rhetoric seemed to take a sharp turn to the right in 2015 as he approached re-election. His campaign thumped repeatedly on his conservative bona fides – his long-standing support for gun rights and anti-abortion voting record.

Perhaps most notably, Crapo went on “Tea Party Bob” Neugebauer’s radio show in spring 2015 and praised nine Republican Idaho legislators for “doing their jobs” in maneuvering to defeat a must-pass child support enforcement bill on state sovereignty grounds. The Legislature was forced to hold a special session later that spring to pass an amended version of the bill.

Crapo said in a statement afterward that he supports child support enforcement and wasn’t taking a position on the legislative fight. And he maintains now that his comments on the radio show were misconstrued. But he defends his rhetoric through the year, which apparently succeeded in heading off any challenge from the right in the GOP primary, in which he was unopposed.

“I have always been very, very conservative,” Crapo said. His ratings from the American Conservative Union, which has been rating members of Congress for the past 45 years, bear that out: In 1996, the group gave him a 95 percent rating. In 2015, it was 96 percent.

Following in brother’s footsteps

Crapo was just 15 when his older brother, Terry, was elected to the Idaho Legislature. Within two years, Terry Crapo would rise to become House majority leader.

“That’s what got me first exposed and first interested,” Crapo said. “I worked on his campaign, and I visited him in Boise.”

After graduating with honors from Brigham Young University, Crapo served as an intern for then-Idaho GOP congressman Orval Hansen. It was the summer of the Watergate break-in.

“I can remember the next year, just being fascinated with the whole process of the investigation and the hearings and the ultimate outcome of the Watergate situation,” he said. “I know all of that increased my interest in politics.”

When Crapo was admitted to Harvard Law School, he was following in his brother Terry’s footsteps.

“I wanted to be like my brother,” he said.

As a young lawyer, Crapo clerked for a 9th Circuit Court of Appeals judge in San Diego for a year, then accepted a position with a big Los Angeles-based law firm that was opening an office in San Diego. After a year, he moved back to Idaho and went into practice with his brother.

Terry Crapo died of leukemia in 1982 at age 43. Two years later, Mike Crapo was elected to the Idaho Senate.

He ran for office despite his brother’s warning that practicing law full time and also serving part time as a state lawmaker is a big, difficult-to-manage time commitment.

Like his brother, Crapo was elected to a leadership position, assistant majority leader, in just his second term. He ran for president pro tem, the Senate’s highest leadership post, in his third term and won. The Senate leader he succeeded, Jim Risch, had been unexpectedly defeated for re-election that year; Risch is now Idaho’s junior senator, serving with Crapo.

“I got pulled further into the statewide politics because of that leadership position, and it just got very, very busy,” Crapo said. “I was still practicing law full time and trying to be the pro tem of the Senate, and there wasn’t enough time to do it. So I had to either quit the Legislature and practice law full time or run for Congress,” turning his legislative work into his full-time job.

Elected to the U.S. House, Crapo again rose swiftly into leadership, starting with election as leader of his freshman class.

“I think you can have a greater impact by being in leadership,” he said. “I was actually in the leadership room for the six years I served in the House.”

Crapo briefly considered running for governor in the 1990s, acknowledging that family considerations made it desirable to return to Idaho. His wife, Susan, and five children still lived in Idaho Falls, often seeing him only on weekends. But he ended up sticking with his path in D.C.

When he moved from the House to the Senate in 1998, he ran for an open seat as then-Sen. Dirk Kempthorne ran for governor. Crapo quickly adjusted to the Senate’s slower pace and need for a bipartisan majority to move any legislation.

Crapo is now the chief deputy whip in the Senate’s Republican leadership team – the No. 2 position under Majority Whip John Cornyn – and also has chaired the “Committee on Committees” each session of Congress since 2004. That’s a key position, appointed by the majority leader, that requires him to work with every member of the caucus and handle negotiations on which senators get on which committees. Though it’s called a committee, he’s the only member.

Cancer diagnosis ‘an entire shock’

Crapo was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1999, his first year in the Senate. “It’s just an entire shock when one gets that kind of a diagnosis,” he said.

He underwent surgery in 2000 and was pronounced cancer-free, but it recurred in 2005, and he began radiation treatment. “That was basically every day except weekends for six weeks,” he recalled. “It weakens you.”

He still tried to keep up with his Senate schedule.

“I made it to almost if not every vote,” he said.

He remembers returning from a radiation treatment while an important vote was pending in the Senate, and hitting a traffic delay. “I was on the phone with one of the floor leaders, saying, ‘I am coming, hold the vote open.’ ”

Crapo already had made health and funding for biomedical research a big priority in his Senate career, partly as a result of having two brothers, an uncle, a brother-in-law and two sons who are doctors.

But he said his experience with cancer strengthened his understanding and commitment to health issues. He became an advocate for men’s health, and for years he sponsored booths at county fairs around Idaho encouraging men to get tested for prostate cancer.

‘Building block after building block’

Crapo’s legislative record is more substantive than flashy. But if he succeeds in winning a fourth term – and the polls have him heavily favored – he’ll be the first Idaho senator since Frank Church to do so. Church was a famed national figure, a Democrat who ran for president, opposed the Vietnam War, crusaded against abuses by the CIA and FBI and had major influence on the nation’s foreign and domestic policies in the 1970s.

Steve Shaw, political science professor at Northwest Nazarene University, said of Crapo, “For being on the verge of entering his fourth term, he still doesn’t strike me as being a national figure – in part because of his style.”

Maya MacGuineas, head of the Campaign to Fix the Debt and president of the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, has worked with Crapo on the federal debt issue.

“He’s not somebody I see pushing other members aside to get to cameras,” MacGuineas said. “He’s somebody who sits down with spreadsheets and prints out reams of paper on tax policy.”

MacGuineas called the Simpson-Bowles budget-balancing proposal “the biggest accomplishment that I’ve seen in the course of my career.”

“And that’s not to say we’ve gotten the job done; we haven’t,” MacGuineas said. “But this is a very difficult issue that requires building block after building block after building block. We wouldn’t even be building if they hadn’t come up with the Simpson-Bowles proposal.”

Crapo says some pieces of what he worked for in that effort have been passed since then, including caps on discretionary spending and some budget process reforms.

“The big, comprehensive bill has not been done yet – parts of it have,” he said. “Other parts of it have moved down the road significantly.”

He’s built seniority on two major Senate committees, banking and finance, while also serving on the budget committee; that gives him a say in budget debates. The finance committee’s jurisdiction covers taxes, all aspects of generating revenue and entitlement programs including Medicare and Medicaid.

But it’s the banking committee on which Crapo is the ranking GOP member, meaning he’ll likely become chairman if Republicans hold their Senate majority in November. That panel has oversight of financial institutions, economic policy, the insurance industry and securities markets.

It’s also an area rich with interested parties who contribute heavily to political campaigns. That’s partly why Crapo has amassed such a huge campaign war chest – more than $5.1 million in cash on hand as of the close of the last reporting period.

In addition, the same interests have contributed to Crapo’s political action committee, the Freedom Fund, which has raised millions and hands out big donations to other Senate candidates and state and national Republican Party committees.

According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the top five interests that have contributed to Crapo over his career are securities and investment; insurance; leadership PACs; commercial banks; and health professionals.

He said it’s his commitment to “a free market and reducing government regulation” that draws those donors to his campaign.

“I am still advocating for the very same things I said I would in my very first campaign,” he said.

Crapo has been the lead sponsor of 63 bills in the past six years. The most common topics were tax credits and deductions; restricting the Environmental Protection Agency or other federal agencies; health care; and tribal issues.

He also serves on the Indian Affairs Committee and the Environment and Public Works Committee. In the most recent session of Congress, he sponsored 29 bills, twice as many as Risch, his fellow Idaho senator.

But the more remarkable number is seven – the number of Crapo’s bills signed into law in his most recent six-year term. That’s come as Congress has been in one of its least productive periods in modern history.

Shaw, the political science professor, said, “You could sure argue he’s picked some good issues very carefully, that while they may not be real sexy are a way to establish a real record and work with some key groups.”

Just this year, Crapo saw his Indian asset trust reform bill signed into law, which gave Native American tribes more autonomy over the management and use of their assets held in trust by the federal government. Also signed was Trevor’s Law, a measure named after Boise resident and cancer survivor Trevor Schaefer that requires federal agencies to document and track childhood and adult cancer clusters.

Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., was Crapo’s leading Democratic co-sponsor on the Indian trust asset bill. Sen. Barbara Boxer, D-Calif., joined him on Trevor’s Law.

Still, he says he’s willing to say no.

“Often I and some of my colleagues get accused of being obstructionist,” he said, noting that he’s voted against budget bills and measures related to the Affordable Care Act. “There’s a part of the legislative philosophy of holding firm on important things.”

Crapo also has co-sponsored 730 bills and 130 amendments over the past six years.

The single vote that’s drawn the most criticism may have been Crapo’s vote in March 2015 in favor of a budget amendment sponsored by Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, that authorized creation of a “spending-neutral reserve fund relating to the disposal of certain federal lands.” It passed 51-49.

“My opponent and some others are trying to say that that vote represented a desire to sell off the public lands into private ownership,” Crapo said. “It was not anything of the sort, and I have consistently supported the public lands remaining public.”

He said it could have applied to exchanges or other moves that could be part of good land-management decisions. But sportsmen in Idaho decried the symbolism of the amendment and said Crapo could have blocked it. His Democratic challenger, Jerry Sturgill, has seized on the vote as a sign of how Crapo has changed.

Shaw said Crapo’s public statements have grown more conservative as Capitol Hill has become more polarized.

“I wonder if he is trying to convince himself that he hasn’t changed, that his rhetoric hasn’t changed,” he said.

MacGuineas, whose organization is nonpartisan, said, “He is not some sort of centrist. He is a very conservative member who has the temperament of somebody who is not trying to throw bombs, but somebody who is trying to get to yes without compromising his principles, and I admire that a lot.”