Potato farming in Washington involves high-stakes investment due to competitive market, low profit margins

Sun., April 23, 2017 | By Eli Francovich

Rex Calloway looked west through the large windows of his 1950s-era farmhouse near Quincy and talked about the time, nearly 70 years ago, that his grandfather first arrived on this land.

Back then, the Columbia Basin was dry. A rugged landscape of sagebrush and rolling hills. Rattlesnakes. Scorching summer days. Cold nights. Quincy, the nearest town, was a speck, homesteaders and dry-land farmers eking out an existence on an average of 6 to 8 inches of rain a year.

“A huge leap of faith,” Calloway called his grandfather’s decision to move from Oklahoma.

But things were changing and Calloway’s grandfather, who was 60 years old at the time, knew it.

“Water was coming,” Calloway said.

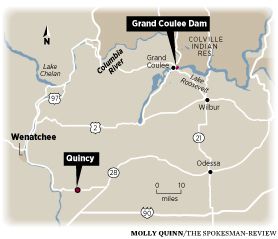

Roughly 100 miles to the northeast, the Grand Coulee Dam was rising. And with it, a massive federal irrigation project that would transform the basin into one of the nation’s richest farming areas.

Now, 70 years later, the Columbia Basin is one of the premier potato-growing regions in the country. While Idaho produces more potatoes, Washington farmers claim efficiency, harvesting about 60,000 pounds of potatoes per acre.

Most of Calloway’s 2,700-acre farm is dedicated to potatoes. When he’s not growing potatoes he plants corn and wheat.

On a recent Friday morning, he is busy. It’s the first day of planting season, and he’s about two weeks behind schedule because of the unusually heavy spring rains.

“It’s thrown a pretty big one (curveball) at us this spring,” he said of the rain.

Calloway is just one piece of a statewide industry with a worldwide reach.

As big as that industry is, it’s not an easy way to make a living. Shrinking profit margins in an increasingly competitive international market make potatoes a high-stakes investment with plenty of risk and little room for error.

And with that competition and specialization comes new demands. Farmers are increasingly expected to be business managers, chemists, mechanics and salesman, in addition to farmers – belying the romantic, pastoral image many nonfarmers may have of agriculture.

“Farming is difficult. This is not easy. This is not easy,” said Calloway, a third-generation farmer. “By God, if your heart is not in this, it will take you down so fast.”

A massive state industry

In an unassuming Moses Lake office, Chris Voigt and Ryan Holterhoff oversee the Washington State Potato Commission. Baskets of sample potatoes sit in the entryway. Washington state potato souvenirs line the walls.

Voigt is the executive director of the potato commission, which helps fund potato-related research, works to develop export markets and advocates for farmers at the state and national levels.

Potatoes are worth $7.4 billion to the state’s economy each year, Voigt said. Although there are only 250 potato growers, the crop creates 36,000 jobs throughout Washington.

Those numbers contribute to the potato’s status as the leading vegetable crop in the United States, representing about 15 percent of all farm vegetables sold, according to the United States Department of Agriculture. Washington accounts for 23 percent of the national industry.

The first domesticated potatoes were grown in present-day Peru and Bolivia between 5000 B.C. and 8000 B.C.

In fact, according to one 1990s economics study by Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian, the cultivation of potatoes accounted for roughly one-quarter of the growth in the Old World between 1700 and 1900.

In 1995, a potato became the first vegetable grown in space. When humans go to Mars, potatoes may very well come along too. In 2015, potatoes played a prominent role in the Matt Damon movie “The Martian.”

Washington potatoes are an integral part of this worldwide industry. Yet the scope of Washington’s potato industry isn’t known by the average consumer, said Holterfhoff, the director of marketing and industry affairs for the potato commission.

“We have this very important and vibrant potato industry going on here in Washington,” he said. “And if you get outside of the Columbia Basin, a lot of people don’t even know that exists.”

That’s largely because about 70 percent of the 10 billion pounds of potatoes grown annually in Washington are exported.

“Right now the country of Japan buys more potatoes from Washington than anywhere else in the world,” Holterhoff said.

Blame the weather. Four typhoons hit Japan’s richest agricultural region in August, decimating the country’s own potato industry and causing a potato chip shortage.

American consumers also rarely see Washington potatoes on the supermarket shelves, because most are sold to processing plants in Washington – like Lamb Weston, Simplot and McCain Foods. These plants process the potatoes, turning them into french fries, potato flour, potato chips, frozen potato products or other goods.

And although nearly all Washington potato farms are family-owned and operated, they aren’t stereotypical mom-and-pop operations. Instead, they’re large, sophisticated multimillion-dollar businesses that rely on cutting-edge science and technology. On average, potato farms cost about about $5,000 per acre to run. That’s on top of the cost of irrigated land, which can be between $12,000 and $15,000 per acre.

And that largely has to do with the increasing competitiveness and difficulty of modern farming.

“If you have a decent year, a good year you might make 4 percent return on your investment,” said Voigt, the executive director of the state commission. “If you have something bad happen, you’re going to lose money.”

The small margins, combined with the high-tech machinery necessary to grow potatoes on a large scale, make consolidation and expansion a necessity.

“The margins have gotten so slim,” Voigt said. “To make a living for your family anymore, you have to grow bigger.”

No cold starts

When Calloway’s grandfather came to Washington, he bought land and started farming. Now, that’s nearly impossible with little available land and the high startup costs of modern agriculture.

Although sometimes an established farmer will hire or train a new farmer, starting from scratch is too expensive, and too risky. Unless, Calloway joked, you’re Jeff Bezos.

“To start farming, just to come into it cold, it doesn’t happen,” Calloway said. “You do not get somebody cold-starting a farm.”

The lack of new farmers underscores another underlying problem for potato farmers and agriculture in general.

As younger generations become increasingly disinterested in farming, family farms often are auctioned when elder farmers retire.

Calloway has two sons, a 15-year-old and a 12-year-old, and although they help around the farm in the summers, it’s not a sure bet that they will take over the farm when he retires.

“Are my boys going to farm? I would love it for them to farm,” Calloway said.

But his boys may choose not to. If that happens, Calloway might be forced to auction his farm.

The average age of the American farmer was 58 years old in 2012, according to the U.S. Agricultural Census. What’s more, the number of new farmers – those operating for 10 years or less – dropped by 20 percent between 2007 and 2012.

“I’ve seen more auctions this year than I’ve ever seen,” said Paul Wollman, the farm manager at the Warden Hutterian Brethren farm, east of Calloway’s farm. “This, here, is getting to the point where it’s a big concern.”

More management, less dirt

“It’s what we’ve been doing for many generations,” said 21-year-old Nick Wollman while perched in the cockpit of a half-million-dollar potato planter.

He added, “These are my spuds. I’m not working for somebody else. It’s not my job. It’s my responsibility to make sure these get planted right.”

Wollman watched four video screens showing recently cut seed potatoes being deposited into the rich earth of one of the Hutterite fields. The tractor is GPS-controlled, driving in nearly perfect half-mile lines. Wollman’s job is that of machine overseer. He makes sure systems are running correctly, that the potatoes are evenly spaced and chemicals evenly applied. And then, when he reaches the end of a row, he turns the machine around, and lets the GPS take over again.

Wollman is one of the 126 people who live at the Warden Hutterite Colony near Warden. The colony was founded in the early 1970s as an offshoot of a Spokane colony. They trace their religious and cultural roots to the 1500s and the Protestant Reformation.

Paul Wollman, Nick’s uncle, insisted that despite the farm’s sophistication, at its core, it’s essentially a big family farm.

“We’re a family farm, and we are uniquely different from the farmer down the road,” Paul Wollman said.

But what really makes the Hutterite situation unique, at least as far as farming goes, is the communal ownership.

“I can’t say this is mine,” said Paul’s older brother, Albert Wollman. “It’s all ours.”

Nick Wollman’s attitude toward his job illustrates the communal buy-in at the Hutterite Colony. Unlike most potato farmers, and farmers in general, the Hutterites don’t rely on seasonal labor. Instead, they work together to plant and harvest the potato crop.

Back at Rex Calloway’s farm, in a dimly lit, steel-reinforced concrete hangar, he’s addressing a crew of six Hispanic workers he’s hired for the planting season.

Calloway, a tall, lean man, hunched slightly to be heard by the shorter men and women gathered around a stopped conveyor belt. Potatoes sat on the belt bed. Small upturned paring knives are attached to the sides of the metal bin.

“Does everyone understand English?” Calloway asked. One woman shook her head.

So one of Calloway’s full-time employees began to translate.

“What I’m trying to stress to you is safety,” Calloway said. “Your hands only stay on the top deck.”

These kinds of administrative concerns occupy most of Calloway’s days, making him in some respects more of a manager and less of a farmer.

“I haven’t sat in a tractor in 15 years. I don’t plant, I don’t till,” Calloway said.

Later, he clarifies that on a regular basis he doesn’t sit on a tractor, instead overseeing the farm’s operations.

Calloway misses that hands-on work. He misses having dirt on his hands. So does Albert Wollman, Paul’s older brother.

“Used to be we spent them (winters) in the shop fixing stuff,” he said. “Now you spend them getting your certifications.”

American nostalgia

Those changes underscore a profound shift in how American farmers ply their trade. Although food packaging and the popular imagination still depict pastoral scenes of quiet country work, the reality is different.

While planting on an April afternoon, Nick Wollman reflected on the changes brought about by technology.

“Farming is a lot easier. It is not easy, but it’s a lot easier nowadays,” he said.

As evidence of the increased ease of farming, Wollman pointed to the tractor he’s driving, or, to be more precise, monitoring. The GPS-guided machine travels up and down the rows in perfectly straight lines, with little or no human input.

Wollman has never driven a tractor that was not GPS-steered. His father, Albert Wollman, remembers the mental drain of focusing on driving straight lines for 10 or 12 hours a day. To keep the rows straight over a half-mile line, farmers marked out rows with rolls of paper towels half buried in the dirt every 150 feet.

With the GPS guidance, Albert Wollman gets to read, often spending the days buried in the Wall Street Journal or the Atlantic.

“You get an opportunity to sit and think and whatever, read a book,” he said of the planting season.

While planting, Albert and Nick communicate via radio. At one point, Albert’s tractor stopped and he jumped out and started digging into the soil. Then he got back in his tractor and started to back up.

“My computer crashed so I’m going to have to replant this row,” he told Nick over the radio.

The cultural underpinnings of Calloway’s farm, and that of the Hutterites, is one based on an ideal: the resilience and reliance of farmers, perpetuated in American culture through generations.

However, these same operations increasingly depend on mechanized and specialized machinery. Machinery that comes at a cost.

“I don’t get my hands dirty. I have guys who get their hands dirty,” Calloway said. “I miss it. I’d rather sit on a tractor.”