There was no president on this date 175 years ago. Or was there?

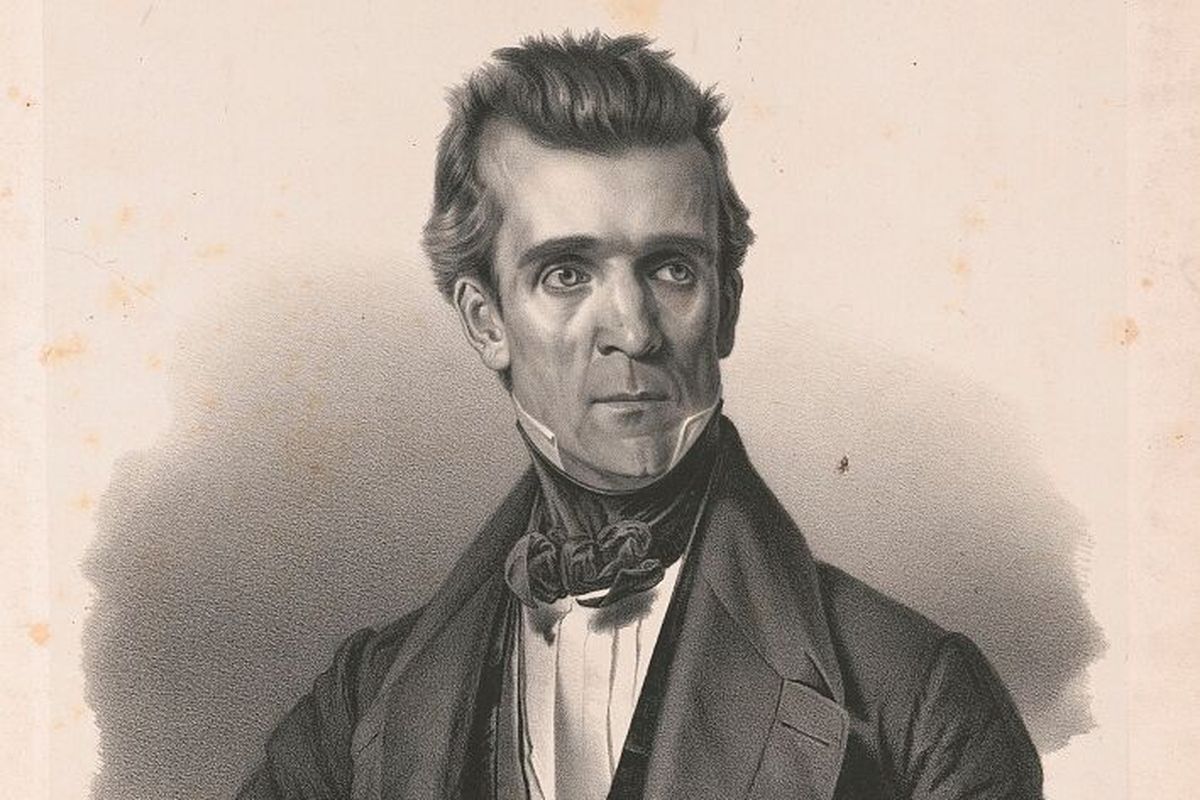

James K. Polk’s final night as president of the United States was an all-nighter.

“The 11th President had spent the previous evening with Congress trying to pass some final appropriation bills before turning the Oval Office over to the incoming Zachary Taylor,” Polk wrote in his diary in the early hours of Sunday, March 4, 1849, “thus closed my official term as President.”

But did it? Back then, presidential terms expired at noon on March 4. But because the day fell on a Sunday, Taylor didn’t want to take the oath of office in violation of the Sabbath. The situation created one of history’s strangest footnotes - a controversy over who, if anyone, was actually president on that date 175 years ago.

It also led some people to believe that the 12th president wasn’t actually Taylor but Sen. David Rice Atchison (D-Mo.), the Senate president pro tempore at the time, whose tombstone reads “President of the United States for One Day.”

Polk himself was unsure whether his term expired at 12 a.m. or 12 p.m. on March 4, which was the constitutionally mandated Inauguration Day from 1793 to 1933, roughly a month and a half later than it is today. In an attempt to follow the Constitution and advance the appropriation bills, he split the difference and stayed up all night, working into the morning of March 4.

“Whether that was out of expediency because he was concerned about that appropriations bill getting passed or he believed that really from a constitutional standpoint is debatable,” said Tom Price, who served as the curator of the Polk home and museum in Columbia, Tenn., for 21 years. “But it’s kind of interesting that nobody seemed to know.”

After writing in his diary that his term was over, Polk exited the White House and stayed at the Irving Hotel in Washington. Because Taylor wasn’t sworn in until the following day, who ran the country that day remains a debate of constitutional interpretation and presidential succession that has never been fully answered. (Polk died of an illness just three months after leaving office, and Taylor died in office less than a year and a half into his presidency.)

Had an emergency situation arisen after noon on March 4, 1849, it might have been the ultimate test of presidential power and succession.

Years after Polk’s and Taylor’s deaths, Atchison’s legend grew.

Atchison served as president pro tempore of the Senate more than a dozen times while Polk was in office. At the time, the president pro tempore served as a substitute for the vice president when the latter was absent from Congress, and he was third in line to the presidency. (The speaker of the House is third in line today.)

Two days before Polk left office, his vice president, George Dallas, ended his term by taking a leave from the Senate session. Atchison was elected president pro tempore in his place.

Polk’s term technically expired at noon that Sunday, even though indications are he was out of the White House before then. In theory, with Taylor not sworn in until Monday, Atchison would have become president at that point.

But constitutional scholars have argued Atchison’s term expired when Polk’s did. So how did he get the title of “President for a Day?”

On March 12, a week after Taylor was sworn in, the Alexandria Gazette reported that Atchison was president on March 4. The story began to take on a life of its own and changed over the years, making its way into numerous profiles of Atchison and even a congressional directory. It gained a second life in the early 1900s after more newspapers began running the story.

Atchison lived until 1886, almost 40 years after Polk and Taylor, making him the lone protagonist able to weigh in on the matter. In 1880, he wrote that he had never served as president, and he put some humor behind his argument. Given the all-night Senate session that seeped into the day in question, Atchison said the long evening might have caused him to sleep through his term. He also joked that his “administration” was “the most honest” the country had ever seen.

As for why the tall tale took on a second life in the early 1900s, two decades after Atchison died: It might be his own fault.

“I think because he kind of had fun with it in his day, it led some people to give some veracity to it,” said Daniel S. Holt, an associate historian at the U.S. Senate Historical Office.

Holt said Atchison’s situation reminded him of former Supreme Court justice William Cushing, who accepted the role of chief justice from George Washington, only to decline it a few days later. Historians are split on whether he was or was not the chief justice for a few days.

In addition to his grave, a statue of Atchison in the Kansas City suburb of Plattsburg, Mo., bears the inscription “President of the United States One Day.” Roughly 40 miles to the west is the town of Atchison, Kan., in Atchison County - both named after him. The town claims to have “the world’s smallest unofficial Presidential Library” in honor of Atchison.

“Once historical figures die, their legacy is really out of their hands,” said Lindsay Chervinsky, a presidential historian at Southern Methodist University. “It’s a good reminder that legacy and history or legacy and fact are not necessarily the same thing and pose interesting challenges.”

By all indications, March 4, 1849, was a relatively quiet day after the Senate adjourned in the morning, allowing the Polk-Taylor succession question to fly under the radar of historical fun facts. The country wasn’t at war; Taylor was in Washington, ready to start his term; and no pressing matters remained after the appropriations bills were resolved. Had something required presidential attention, scholars say, Taylor would have been the one to act because not having taken the oath of office doesn’t deny a president their powers or responsibilities, and Polk’s term had already ended.

Presidential succession is generally straightforward. When a president dies in office, the vice president takes over. It’s happened eight times, four by natural death, four by assassination. John Tyler, Polk’s predecessor, was the first to take over in this way after William Henry Harrison died in office; Millard Fillmore became the second when Taylor died in 1850. Most transitions have taken place during peacetime, with no immediate rush for the vice president to be sworn in. Harry S. Truman, the only president to take over while the country was at war, was in Washington and sworn in roughly four hours after Franklin D. Roosevelt died.

“The Constitution was such a well-intentioned plan, but there were so many things that were unanticipated,” Chervinsky said, adding, “I think this is such a great example of all of these things … that no one could possibly foresee.”

The Polk-Taylor transition did leave a legacy. The next time the March 4 Inauguration Day fell on a Sunday came in 1877, a few years before Atchison sought to dispel the notion that he’d been president. But he was clearly top of mind, as officials had incoming president Rutherford B. Hayes take the oath of office on Saturday, a day before Ulysses S. Grant’s term ended, giving the country at least the appearance of two presidents under oath at the same time.

“It would make more sense if he did it on a private ceremony on Sunday,” Holt said. “But nobody wanted to do anything on the Sabbath, so he took the oath on Saturday. You can’t be president until the one term ends, so who knows if that even made any difference.”

Today’s transition period is much shorter, with the new president sworn in on Jan. 20 - unless, that is, it’s a Sunday, in which case the end of the old presidential term and the start of the new one both come a day later, without any gaps or overlap.