Seattle’s newest NBA superstar and his dad’s 90-year-old butcher shop

TUKWILA – In 1932, Mario Banchero’s great-uncle, Ed, who everyone knew as Catfish, opened a small butcher shop in Seattle’s Rainier Valley. Hamburger was 3 pounds for 25 cents. They did a little under $8 on their first day in business.

On Sunday, Mario Banchero’s son, Paolo, will play in the NBA All-Star Game. At just 21, he will be the youngest player in the game.

Paolo Banchero, 2021 graduate of O’Dea High School, pride of South Seattle, in just his second year with the Orlando Magic, has become a franchise cornerstone, one of the league’s brightest young stars, an impossible combination of size, skill and grace, capable of dominating a basketball game from practically any position on the court.

“I really like Paolo, beautiful kid, beautiful player,” Shaquille O’Neal said Tuesday, when asked about his former team, the Magic. “They can compete and they can go pretty far. They just have to believe it. But it all starts with Paolo.”

He is making $11.6 million this year. A year and a half from now, barring calamity, he will very likely sign a contract worth around $200 million.

He is the youngest member of Seattle’s NBA family tree – from Brandon Roy and Jason Terry, through Jamal Crawford and Isaiah Thomas, to Zach LaVine and Dejounte Murray – carrying the weight of the city’s pro men’s basketball culture, bloodied but unbowed, until the Sonics return.

Mario, meanwhile, keeps doing what his family has been doing for more than 90 years – cutting steaks, grinding beef and stuffing sausages.

Mario, and his brother Angelo, run Mondo & Sons, the third generation of their Italian American family to run the butcher and meat distributor.

Paolo’s success, even at such a young age, means his family is financially set for life. But Mario still goes to work. So does Paolo’s mom, Rhonda Banchero, a former basketball star herself, who is now the director for equity and inclusion at Downtown Emergency Service Center, one of Seattle’s largest supportive housing and shelter providers.

They think about it in a couple of ways. There is, first of all, the practical aspect: You need something to do every day.

“My dad has always been a proponent that you’ve got to keep doing stuff, like the minute you just stop, the clock ticks faster,” Mario said.

“We’re workers, we work,” Rhonda said, adding that her own mother, at 74, still works in human resources for the Red Cross.

And there is the weight, the birthright, of a family-owned business, one of the rare remaining throwbacks to a time when the north Rainier Valley was so dominated by Italian immigrants that it was known as Garlic Gulch.

The neighborhood was largely destroyed by the construction and expansion of Interstate 90 in the middle of the 20th century. But businesses that grew out of Garlic Gulch – Oberto’s, Isernio’s sausages, Merlino Foods, Borrachini’s Bakery – became household names in Seattle, even as some closed in recent years. And Mondo & Sons, although it moved from Rainier Avenue to Tukwila and shifted from retail butcher shop to a mostly wholesale distributor, endures.

Mondo, who was born in Italy, was Mario’s grandfather; the “& sons” were his father and uncles.

“Legacy is a big, big thing,” Mario said. “Just kind of knowing where you came from and sort of understanding what that is and being connected to that and then, you know, trying to live up to that and then build on it. I just think it’s a great sort of curriculum for life.”

Butcher coats and bloody aprons

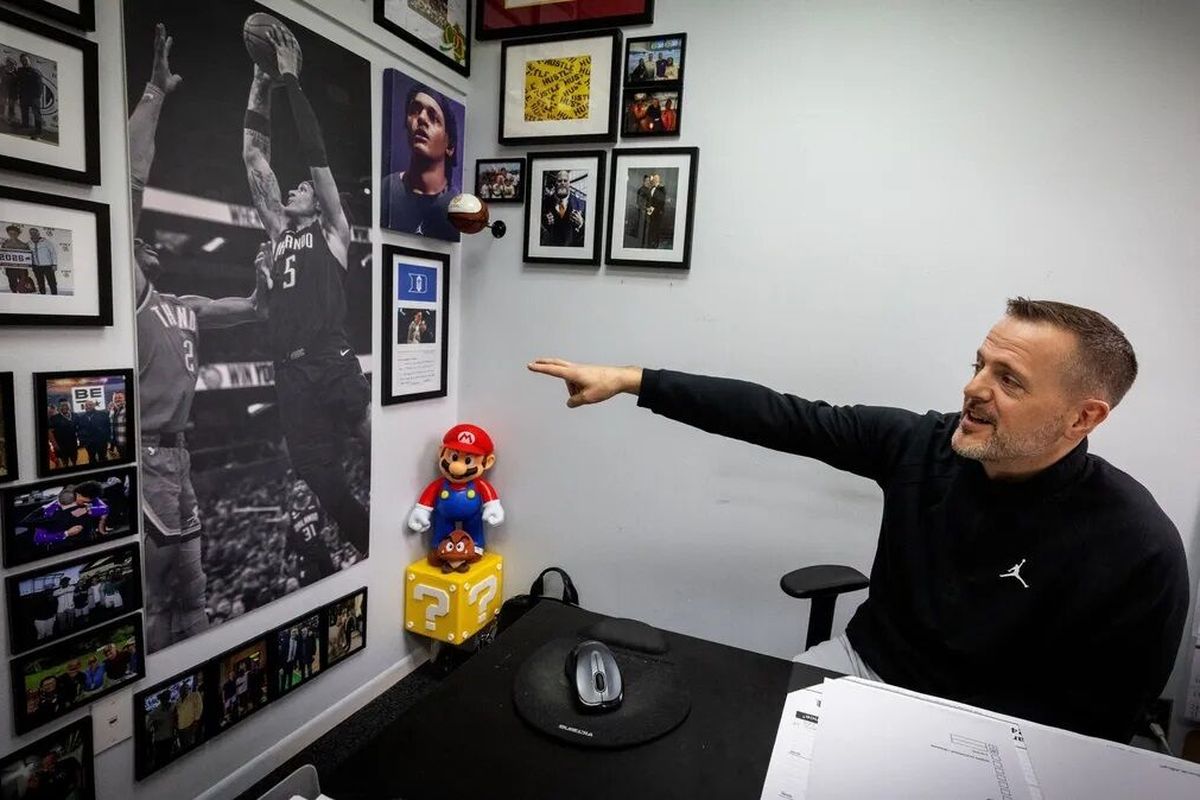

Mario Banchero’s office at Mondo is tiny, maybe 8 feet square. But its walls tell the family’s story, past and future.

On one wall: a giant wooden coat of arms. Instead of crossed swords, a butcher’s knife, a cleaver and a honing steel cross behind a crest with paintings of a wheel of cheese, a lobster, a bottle of wine, a head of cattle. “MONDO’S WORLD,” says the sign, which hung outside the old shop on Rainier Avenue.

On another wall: black and white photos of men in aprons stained with blood, men in butcher coats in front of hanging sides of beef, Catfish raising his arms triumphantly outside his shop, and one photo, which has become the company’s logo, of Mondo dressed in a sharkskin suit, black shirt, collar splayed, gray fedora, holding a steer by the halter.

“The greatest Italian meat guy photo ever, right?” Mario says.

On a third wall: dozens more photos – a family of athletes. The ones of Paolo – seemingly levitating at O’Dea, arms raised in celebration in his one year at Duke, driving to the rim with the Magic, posing with Kevin Durant and Carmelo Anthony – are most prominent, but others show Mario and Rhonda’s two younger kids, Mia, a soccer player at Queens University of Charlotte, North Carolina, and Giulio, who plays football at O’Dea.

There is a handwritten note from University of Kentucky basketball coach John Calipari, thanking Mario for the “generous gift.”

Calipari recruited Paolo to Kentucky, flying in the family, taking them to dinner, showing them around campus. When Paolo chose Duke instead, Mario sent Calipari (and the coaches at three other schools they’d visited) a box of steaks.

“Some wagyu, some dry aged, some bone-in New York, it was good stuff,” Mario said. “I just really appreciated what all the coaches had done.”

And there are photos of Rhonda, who graduated from the University of Washington as the Huskies’ all-time leading scorer and played professionally in the ABL, the WNBA (the first-ever UW player drafted), in China and in Greece.

Mario and Rhonda grew up about three blocks apart in the Mount Baker neighborhood, where they still live.

“We knew all the same kids growing up,” Mario said. “She was a standout athlete, you know on the news in high school and things like that and then a top recruit.”

He went to O’Dea, she went to Franklin.

They never met until both were at UW, where he was a walk-on tight end on the football team.

When they had their three kids, the family business was just part of the background of growing up.

When graffiti would pop up outside the old Rainier Avenue meat market, “Paolo will tell you that Mario had him out painting fences,” Rhonda said

The kids would sometimes roll their eyes at the stories, she said, “OK, here goes Dad, he’s bringing home the pictures and all these old artifacts from when Mondo’s was in its early years.”

As the kids grew older, she said, the business became a source of pride, and an object lesson in loyalty, endurance.

Mario and Angelo, she said, have both only ever worked for one company. Paolo played for one team his entire AAU career. Mia played for the same soccer club her entire youth career, until COVID-19 threw a wrench in the works.

“Those are things that you just don’t see anymore, you don’t see these immigrant family businesses from 90 years ago that are still going today with the same ownership,” Rhonda said. “They’ve always seen us doing the thing with one team, we stick with our people. If we say we’re coming or we say we’re joining in, you have us lock, stock and barrel.”

‘Everybody’s around a TV’

Working out of a Tukwila warehouse and processing facility, about 10 miles from where Catfish started out, Mondo & Sons has about three dozen employees serving a passel of wholesale customers and a smattering of retail orders.

Angelo’s wife, Misty, has become a bit of a social media meat sensation (@seattlebutcherswife on Instagram, 78,000 followers), so people sometimes walk into the Tukwila business and ask for a few steaks. They don’t have display cases or anything, but they’re happy to comply.

But the bulk of their sales are restaurants, health care facilities and grocery stores.

Taco Time Northwest buys nearly a million pounds of beef a year from Mondo & Sons, that Mondo grinds and delivers fresh to the local chain’s 77 Western Washington restaurants.

Over the past year or so Taco Time has worked with Mondo to produce a home retail version of one of its more well-known items – the crispy beef burrito. Like a large taquito, each one is hand-rolled and fried in house at Taco Time.

It took six months of testing to prepare the same product, at scale, in Mondo’s facilities where they can be par-fried and frozen for home delivery, through Smith Brothers.

“Mario, he’s manning a fryer and cooking burritos for us and we’re taste-testing them,” said Robby Tonkin, co-president and owner of Taco Time Northwest. “It just highlights the cloth they’re made of, Mario and Angelo. With a son who’s a multimillionaire, I would imagine they don’t need to work like they are working now, but there has been no change.”

Mondo & Sons makes 18 or so kinds of sausages that are sold at PCC and Metropolitan Market.

Paolo’s games draw a crowd at Mondo & Sons. East Coast games usually start at 4 or 5 Pacific time, just as the workday is ending. Five or 10 guys will usually crowd into a small conference room to watch the game.

“I stopped watching the NBA once the Sonics left, right? Once Paolo got in …” said Pete Mitalas, a salesman at Mondo for 15 years who is also Paolo’s godfather. “The game comes on and everybody’s around a TV. It’s definitely fun to watch. It’s kind of weird seeing someone that you know, you’ve known your whole life, and now they’re a superstar.”

There was a low-key buzz in the office last week, as the NBA’s trade deadline approached and sales calls were interspersed with checks on Woj and Shams (the guys who break NBA news) to see if the Magic would make a deal.

“It’s like, oh I saw that Chuma Okeke sprained his toe or whatever,” Mario said, citing an Orlando reserve. “Everybody’s got an antenna to what’s going on with the Magic.”

Angelo’s son, Evan, is now working for Mondo, the fourth generation of the family to join the business.

So was there ever talk that Paolo, who’s been playing in All-American games since middle school, would get in the family business?

“The short answer,” Mario said, “is no.”