How did we go from the trustworthiness of “Uncle Walter” and “Chet and David” of the 1960s to today, when so many Americans say they neither trust nor like the news media? It has less to do with news reporting and editing and more to do with rapidly changing technology, nefarious manipulators and a public that often doesn’t take the time to stop and engage in critical thinking.

What is fake news?

Once upon a time — a long, long time ago — fake news was fun. Fake news was satire: a way of making fun of the events of the day and, at times, of the folks who brought us news of those events.

Annual Harvard Lampoon editions poking fun at such outlets as the New York Times and Time magazine were hilarious. As was an HBO TV series called “Not Necessarily the News” that ran from 1983 to 1990. As is the “Weekend Update” segment of the long-running NBC late-night sketch-comedy series “Saturday Night Live.”

“Weekend Update” and other similar satire are often presented as humor, though. With a live studio audience laughing at the jokes, it would be difficult to mistake theses shows as real news.

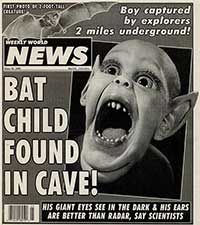

There was also another type of fake news: Fictional stories dressed up to look like real news. The best example of this, perhaps: Supermarket tabloids, in which many of the stories are obviously fake, but some are not quite so obvious.

The danger in this kind of fake news: There are some people who believe these stories are real.

In 1987, the Federal Communications Commission eliminated its long-standing “fairness doctrine,” which required users of public airwaves to provide airtime for opposing viewpoints.

This led to an entire genre of radio and TV shows — Alex Jones, for example — that feature wild conspiracy theories, one-sided political views and downright falsehoods.

There is a sizable segment of the U.S. population that listens to and believes this fake news.

All this has been heightened by the rise in internet usage over the past 25 years. Fake news sites — some aimed at humor and satire, others aimed at deliberately misleading readers — have proliferated. Some of these sites sell advertising, which makes them seem even more like real news sites.

Many social media users tend to pass along links to stories without actually reading them, which just adds to the problem. This has helped create an environment in which it can be difficult to tell the real news from the fake news.

Into this explosive environment came a huge increase in talk TV shows: Sean Hannity. Rachel Maddow. Tucker Carlson. Bill Maher. “Fox and Friends.” “The View.”

Some of these shows feature news segments, knowledgeable guest experts and carefully vetted reporting.

But some do not.

This type of programming has helped condition American TV audiences to the type of “news” that consists of people sitting around and expressing their opinions. Once that happened, the stage was set for ...

The weaponization of fake news and ‘alternative facts’

Political manipulation of the public is as old as politics itself. One might remember from Woodward and Bernstein’s “All the President’s Men” how Nixon campaign operative Daniel Segretti engaged in “dirty tricks” to sabotage opposing campaign efforts. So perhaps it was just a matter of time before modern-day operatives — both within the U.S. and outside the country — used the unstable media situation here to find new ways of messing with the collective American mindset.

ALEX BRANDON/THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Foreign propaganda operations — most notably, Russia and China — have seized upon social media outlets to spread fake news stories and rumors that, all too often, U.S. users regard as real information.

Twitter has recently begun removing accounts caught spreading false news narratives — and has taken a bit of heat from certain political circles for that. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has promised changes on his platform but those have seemed slow in coming.

Some of this fake news propaganda hit a high point during the 2016 election. Media experts have warned that without major changes, it could happen again this year.

The Donald Trump administration has capitalized on this situation by repeatedly changing its story and then denying earlier statements. White House counselor Kellyanne Conway in January 2017 famously referred to what NBC’s Chuck Todd called “a provable falsehood” as “alternative facts.”

This has increased over time. As reporters fact-check the administration or Trump’s statements, they are yelled at, bullied, called names and told they are “fake news” — basically, any journalist who questions whatever the President is saying at the time is guilty of engaging in “fake news.”

In the beginning, it was simple name-calling. But as Trump’s media-bashing continued and intensified, it has led to harassment of and threats against journalists — especially those covering Trump’s occasional campaign rallies.

This language has escalated since the start of the coronavirus crisis. The president has bashed reporters — in person via Twitter — who attempt to call attention to false statements and shifting narratives during press conferences or on news programs.

Basic truths

-

Questioning the president — or any other government official — on his actions, his statements or apparent changes in policy based on his statements is not wrong. This is, in fact, the role of the media in a democracy.

-

Calling a journalist “fake news” doesn’t make him or her guilty of producing fake news. Claiming a news organization is “failing” doesn’t make it so.

-

Journalists are not the “enemy of the American people.”

-

At best, the term “alternative facts” seems like a fancy word for propaganda. At worst, it means outright lies.

-

This isn’t just a Republican thing. Democrats engage in fake news — and false claims of fake news — as well.

How can I deal with fake news?

-

Be skeptical as you use social media. If a news story is so weird or so strange that it’s too good to be true, then that might very well be the case.

-

Consider the source. Is it one you can trust? Trustworthy sites might include The Spokesman-Review, the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal. You might want to avoid passing around anything from InfoWars or WorldNewsDailyReport.

-

If a source is one that’s led you wrong in the past — say, MSNBC or Fox News — check to see if the story is from their news divisions or if it’s commentary from their various talk shows. Generally speaking, NBC News and Fox News run pretty solid news divisions. Opinions may vary about their commentary programming.

-

How is the language in the news story you want to pass along? Many fake news stories are posted overseas by people who may not use proper English grammar or spelling. While any U.S. journalist can make mistakes and typos, those are often caught and fixed by editors. With fake news, not so much.

-

Check the date. Sometimes, old stories rise from the dead to circulate again on social media.

-

There are sites that are intentionally designed to look like real sites. Breaking-CNN.com, for example, is a hoax site disguised as CNN. In particular, be on the lookout for sites that end in something.com- something. A dot-com with a dash after the “com” is a sign that someone may be trying to hide who they are.

-

If you do pass along something from a comic/satirical site — say, the Onion — you might add to the top of your post something like: “Funny stuff; I sure am glad this isn’t real.”

Where can I fact-check something?

-

AP Fact Check

The Associated Press chases down rumors and false stories and then tells you the real story.

apnews.com/APFactCheck -

Politifact

Operated by the nonprofit Poynter Institute, a journalism think tank in St. Petersburg, Florida.

politifact.com -

FactCheck

Operated by the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center.

factcheck.org -

Snopes

One of the more prolific sites that covers social media posts and memes.

snopes.com -

Various news outlets

Many have their own fact-checking operations. Two in particular to know:

washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker nytimes.com/spotlight/fact-checks