Few pot convictions thrown out in Spokane, as Washington state considers similar amnesty law

Local evidence suggests some lawmakers’ concern that there will be a rush to erase past misdemeanor marijuana convictions under a proposed Washington law may be overblown.

Just three misdemeanor city cases of marijuana possession have been overturned since a local law went into effect in December 2015 enabling those with minor Spokane cases to ask the court to toss them after the drug was legalized, according to municipal court figures. City lawmakers said at the time of passage that more than 1,800 misdemeanor cases could be eligible.

“I wish more people would take advantage of it,” said City Council President Ben Stuckart, a champion of the city program that made national headlines when it was unanimously passed by the council more than three years ago. The bill became law without Mayor David Condon’s signature.

Now, Washington lawmakers are pitching similar legislation for the whole state. They say it could help tens of thousands of defendants with misdemeanor convictions in state courts. The bill passed the state Senate earlier this week on a 29-19 vote, and enables those with convictions when they were over the age of 21 to appeal to their sentence and have those convictions erased from their records. Up to 68,000 cases could be reviewed under the proposed law, according to a fiscal analysis provided by legislative staff in Olympia.

“It’s the residue that’s left over from the war on drugs,” said Lara Kaminsky, executive director of Cannabis Alliance, the trade group pushing for the bill’s passage. “For those people that are caught up in the system, it’s being able to fully integrate them into society. Getting housing, student loans, or even being able to volunteer at their children’s schools.”

A misdemeanor conviction, whether it’s at the federal, county or municipal level, has the same effect on a defendant, said Jeffry Finer, a civil rights attorney practicing in Spokane and former head of the Center for Justice. The question is often asked on employment paperwork, housing agreements and other official documents.

By requiring defendants to approach the court on their own initiative to erase the charges, lawmakers may be limiting who will actually seek to have their records cleared, Finer said.

“It’s an unknown, and kind of a scary process to go to court at all,” said Finer. “Other than an adoption, or a name change, everyone else is avoiding court.”

The data isn’t just limited to Spokane.

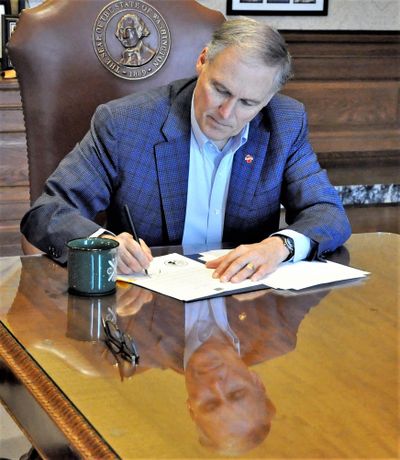

Gov. Jay Inslee, in announcing a process of pardons for those with such crimes on their record earlier this year, suggested that the action could apply to 3,500 cases in Washington state. As of this week, 17 such pardons had been granted, according to reporting by the Associated Press.

Seattle municipal judges acted on instruction from Mayor Jenny Durkan and City Attorney Pete Holmes last fall to automatically vacate city misdemeanors for pot possession, avoiding the issue of requiring defendants to come forward to receive new hearings. Stuckart said he preferred that approach, but the city prosecutor’s office cautioned that such notification would be beyond their capabilities.

Frank Cikutovich, a local criminal defense attorney who has specialized in marijuana defense cases, said after Spokane passed its law he didn’t see many of his clients rushing in to take advantage of the new system.

“We had one person, since it passed, and she worked in the nursing field and she needed it done,” he said.

Others took advantage of the system already in place for vacating misdemeanor charges from their record, Cikutovich said. Under that system, a defendant has to wait for three years after their sentence is completed and pay all legal fines imposed.

Still, much of the debate over the bill has centered on the possibility that the state law would go further than lawmakers intended.

State Sen. Jeff Holy, R-Cheney, offered an amendment in the Senate that would have limited eligibility to just two cases of misdemeanor possession, an effort to weed out frequent lawbreakers who may have pleaded down to misdemeanors from more serious trafficking charges.

“They might say, ‘Gee, you got caught with a joint in your pocket,’ ” said Holy, who spent 22 years in law enforcement with the Spokane Police Department before entering politics. “That’s not the way it works.”

Holy has also argued that vacating convictions won’t eliminate other records of an arrest, a point on which he and Finer, who advocates for blanket pardons, agree.

“This will not fix the piles of public data that exist in private databases all over the country,” Finer said.

Rep. Marcus Riccelli, D-Spokane, said the measure’s time has come, even if it is only used by a select few of the intended audience.

“It just seems like the right thing to do,” Riccelli said. “Maybe we need to look at what we are doing to educate people about what’s available?”