Tony Bamonte, sheriff and Spokane historian who exposed corruption in law enforcement, dies at 77

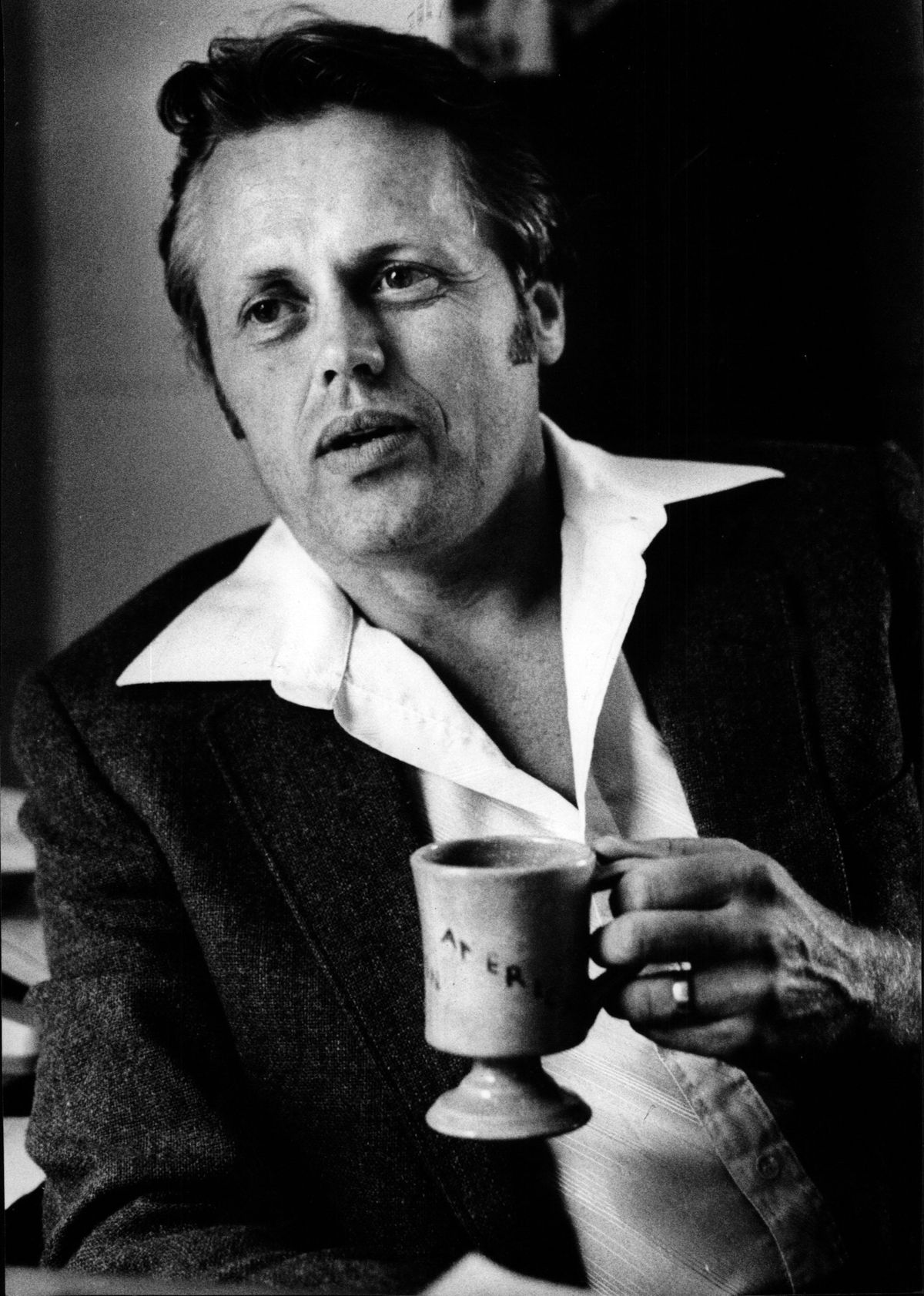

Tony Bamonte, a three-term Pend Oreille County sheriff and prolific local historian who unearthed evidence of a police cover-up in the murder of the Newport town marshal 54 years after the crime, died Thursday morning. He was 77.

The cause was pancreatic cancer.

Born in Wallace, Idaho, Bamonte grew up the son of a miner in Metaline Falls, Washington. He served as a military policeman for the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War before joining the Spokane Police Department in 1966 as a motorcycle patrolman and served as one of the members of the department’s first SWAT team.

That was the start of a long law enforcement career that was, at times, confrontational. Timothy Egan, the New York Times writer who chronicled Bamonte’s dogged pursuit of the truth about Depression-era corruption in the Spokane police force in the book “Breaking Blue,” said that was because Bamonte had a strong sense of morality that was tied to his military service and upbringing.

“The amazing thing about him, he had a stubborn streak of right and wrong,” said Egan, who met Bamonte as a reporter for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “He had this old-fashioned sense of right and wrong.”

Former Spokesman-Review reporter Bill Morlin met Bamonte while he was working at the Associated Press. That included covering Bamonte’s encounter with an armed robber inside the Bon Marche department store in October 1971.

“He had a knack for being in the middle of everything,” Morlin said.

Bamonte, responding to a radio report of an armed robbery, shot 35-year-old Jerry Lewis, who had shot and killed a cashier’s assistant on the fifth floor. Prosecutors later ruled the shooting justified, finding that Lewis had raised his weapon at the patrolman’s head before Bamonte fired. Bamonte’s shot struck sunglasses on Lewis’ face – or, as Morlin remembered it, “right between the eyes” of the suspected robber – likely preventing the bullet from killing Lewis.

In 1974, working as a motorcycle officer, he was selected to escort President Richard Nixon to the World’s Fair Expo ’74 in Spokane. At that time, he also spent his nights at Whitworth University, earning a bachelor’s degree in sociology in 1974.

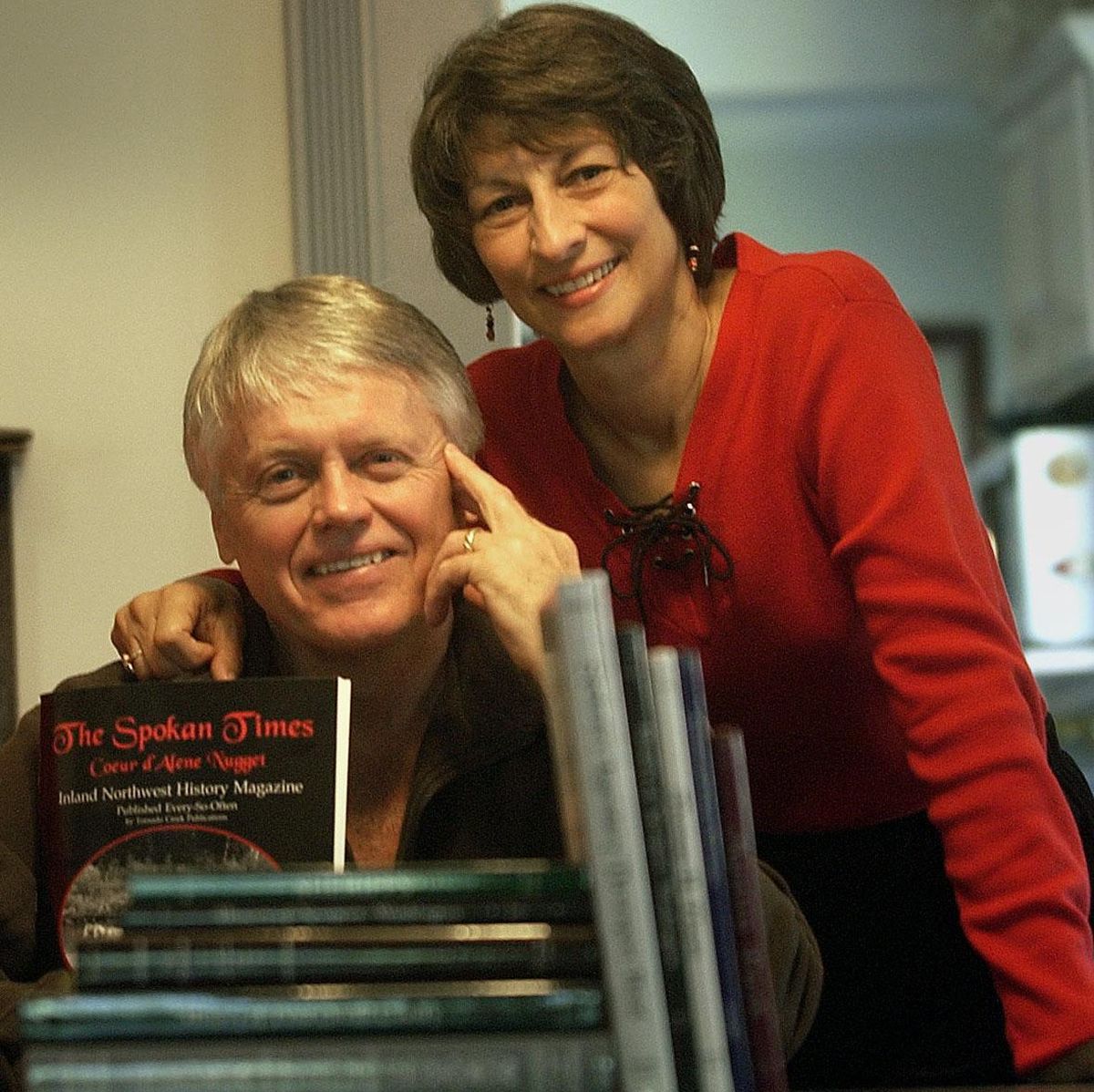

Bamonte left the Spokane Police Department in 1974, according to a biography published on the website of the book publishing firm Tornado Creek Publications, which he ran with his wife, Suzanne. He left for a job as a sheriff’s deputy in Pend Oreille County near his hometown of Metaline Falls, near the Canadian border.

Voters there made him sheriff in 1978, a position he’d hold for the next 12 years. One of his first actions in office was to bring a small claims court complaint against a Spokane tire company, alleging they’d provided him radial tires for his patrol cruisers that leaked air.

“I see this type of thing all the time,” Bamonte told the newspaper in November 1979. “Some businesses think they can just get away with anything when they’re dealing with counties.”

While serving in Pend Oreille County, and seeking a master’s degree from Gonzaga University, Bamonte would launch the investigative probe into Newport Town Marshal George Conniff’s death that landed him on the front page of the New York Times.

Conniff was gunned down in September 1935 in an apparent butter burglary gone wrong at the Newport Creamery. The crime originally was blamed on “fugitives,” according to a Spokane Daily Chronicle report at the time. But Bamonte’s investigation implicated a Spokane police detective in the murder and located a rusty gun in the Spokane River where a witness, and former Spokane police detective, said the murder weapon had been tossed decades earlier.

Bamonte’s examination of the case was featured on “Unsolved Mysteries,” prompting some to claim the gun had been planted by Bamonte. Morlin said Thursday the gun showed signs of rust and corrosion that indicated it had been there a long time.

“People had a love-hate relationship with him,” Morlin said Thursday, after being notified of Bamonte’s death. “He broke that code of silence.”

Three months after the gun was located, Egan submitted his story about the case to the New York Times. It was published in the Nov. 16, 1989 edition of the paper under the headline “After 54 Years, River’s Quirk Gives Up a Clue in Killing.”

“I just thought it was a yarn,” Egan said. “It was a cop-on-cop killing, and it took a cop doing his master’s degree to solve it.”

From that article sprung the book “Breaking Blue,” which looks not only into the killing but Bamonte’s own struggle to unearth the truth. By the time it was published in 1992, Bamonte had lost his post as Pend Oreille County’s top law enforcement officer, losing by 34 votes in a 1990 primary that the incumbent said was partially the fault of the Spokane Police Department.

Tony Bamonte of Spokane stood near the tunnel of the Evolution Mine East of Kellogg, Idaho on Tuesday, September 10, 2013. He was researching and writing a book about the Coeur d'Alene Mining District. (Kathy Plonka / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Then-Chief Terry Mangan, along with the state Attorney General’s Office, had publicly criticized Bamonte for questioning the department’s investigation into the death of David Ritchey, a Spokesman-Review newspaper carrier, in 1987. Bamonte said Mangan was being “too defensive” in dismissing his findings at the time.

That critique from Mangan came after Bamonte publicly questioned whether a Spokane police detective had killed Conniff after the discovery of the revolver in the river.

“I knew I was involved in a lot of controversy and I knew it came at the wrong time,” Bamonte told reporter Jess Walter in an interview conducted as the votes were tabulated in the 1990 primary. “I guess I may be looking for a job.”

Morlin said Bamonte refused to remain silent about behavior he believed was wrong. He noted the recent example of deputies refusing to speak up about a Spokane County Sheriff’s deputy’s allegedly racist comments.

“Tony wasn’t that kind of guy,” Morlin said. “If he saw something wrong, he’d talk about it.”

Bamonte had been working on a book about Ritchey’s 1987 murder, Morlin said. He believed the man imprisoned in the killing, Gregory Rowley, was innocent. Rowley died in custody in 2009.

After the 1990 campaign, Bamonte launched a bid to become Spokane County sheriff in 1994. He was defeated in the primary by Democrat John Goldman and Republican Mark Sterk. Goldman eventually won the general election.

Bamonte and his wife wrote numerous history books together. They include works on the Davenport Hotel, Manito Park and Wallace, Idaho. He also was involved in a series of books from the Spokane Regional Law Enforcement Museum documenting the history of the Spokane Police Department.

His wife said he was an accomplished renaissance man.

“He was always pro-law enforcement,” Suzanne Bamonte said. “There were a lot of things that he forged ahead that upset people. There were people who just loved him, and others who saw him as a turncoat for the people he exposed.

“He was always driven by his integrity and had a kind heart for the underdog,” she said. “He was full of compassion.”

Susan S. Walker, secretary-treasurer of the Spokane Regional Law Enforcement Museum, said Bamonte was known for seeking the truth.

“He has left such a legacy for our area,” she said.

His most recent book, “Motorcycle Officers of Eastern Washington and Relevant Crime Stories,” was published under the Tornado Creek imprint in July 2018.

Co-author and retired Spokane police Officer Jack Pearson said he and Bamonte spent three years collecting information and pictures from former motorcycle cops and their families.

“The more I worked with him, the more I respected him,” Pearson said. “He’s got a heart of gold.”

Pearson also said the Bamontes’ compassion was shown by their willingness to take care of feral cats.

“They treated them like they were their sick children,” Pearson said.

Egan said he didn’t think Bamonte’s writing days were over.

“He was just a great man and had a remarkable, multifaceted life,” Egan said. “I think he had five more books in him.”

Tony Bamonte is survived by his wife, Suzanne Bamonte; his son, Lou Bamonte; his older brother, Dale Bamonte, and his niece, Lani Conrad.

Will Campbell and Jonathan Brunt contributed to this report.