The doctor and the pandemic: Spokane’s 1918 fight against the Spanish influenza

Dr. John Anderson was strolling down Riverside Avenue in downtown Spokane when a man spit on the sidewalk in front of him – a common, if foul, occurrence.

It was also an arrestable offense, as the man would soon find out.

The year was 1918, and Spokane was under something like martial law – but instead of the military giving orders, it was the public health authority.

And Dr. Anderson, Spokane’s chief public health officer, called the shots.

The man, whose name wasn’t recorded in the newspaper account of the incident, wasn’t arrested. Instead, Anderson ordered him to wipe his own spittle off the sidewalk, which he did, with Anderson watching.

The date was Oct. 8, and Anderson could be forgiven for his extreme reaction. Newspapers had been relaying reports of a plague sweeping the world. Influenza, the Spanish flu, la grippe – whatever people called it, was killing thousands of people and infecting many times more. But the people of Spokane had been told not to worry.

Just two weeks before, in fact, the Spokane Daily Chronicle ran an editorial that said “there is no reason to be greatly alarmed … it is a milder type of disease than the old grip,” using an old term for influenza. The “imported type” of flu, the editorial said, was “not available” in Spokane, listing a number of prohibitive “irritations that limit our trade with the Atlantic seaboard.”

“At last the East has something the West does not want,” the editorial said, truthfully if prematurely.

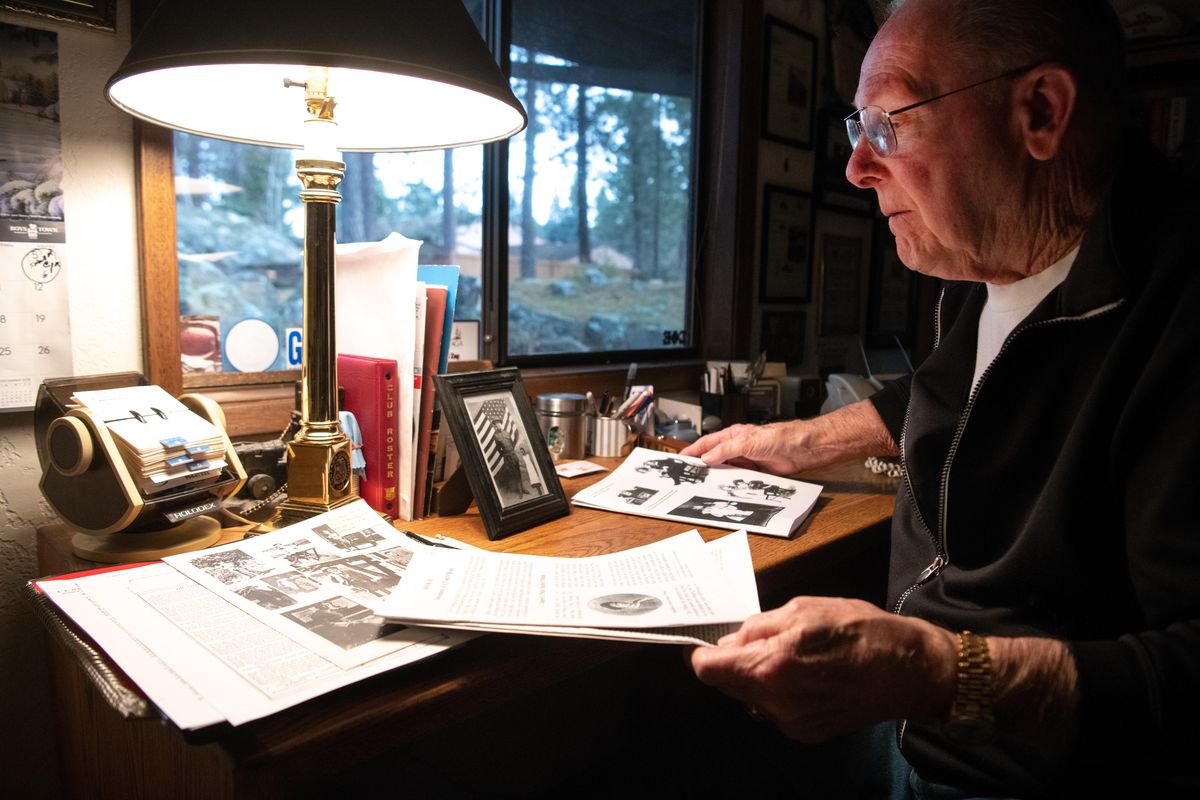

Jesse Tinsley

At the time, in mid-September, Anderson also offered soothing words.

“If Spokane people will sneeze in their handkerchiefs and turn their heads the ‘other’ way when they cough, there is but a remote chance that the city will be attacked by an epidemic of Spanish influenza,” he told the paper.

Over the next 17 days, a lot had changed – namely, the growing pandemic had arrived in Spokane. On Sept. 29, 1918, The Spokesman-Review ran an article headlined “Influenza Here, Public Warned.” One hundred other cases were reported in Spokane in the following week.

Things were getting worse, and on the day Anderson ordered the man to wipe the concrete clean with his own handkerchief, he and 17 Spokane physicians had met to discuss a telegram they had received from the state commissioner of health, T.D. Tuttle, urging them to ban public gatherings.

Anderson and the doctors agreed. At midnight that day, Oct. 8, all theaters, schools, churches, dance halls and every other place where people gathered were ordered closed, as were events like funerals and weddings.

At the time, Anderson couldn’t have known that by the end of the influenza’s course in Spokane, 1,045 people would be dead and nearly 17,000 infected in a city of 150,000 people. He didn’t know that the pandemic would rank among the deadliest events in human history.

If he had, maybe he would’ve arrested the guy.

War brings flu home

The 1918-19 influenza pandemic infected 500 million people worldwide, and killed between 50 and 100 million people – upwards of 5 percent of the human population.

It didn’t spare the U.S., where more than 500,000 people died. Joseph Waring, a medical historian in South Carolina, called it “the greatest medical holocaust in history.” And Isaac Starr, in the Annals of Internal Medicine, ranked it as “one of the three most destructive human epidemics” along with the Justinian plague in the year 541 and the Black Death in the mid-1300s.

At the same time, the world was seeing the end of what would later be called World War I, referred to at the time as the Great War.

The so-called “War to End All Wars” would result in the deaths of 9 million combatants and 7 million civilians, making it the third deadliest war ever, behind World War II and the Mongol conquests of the 13th century.

It’s no coincidence the war and influenza pandemic struck at the same time.

Though the war began in Europe in 1914, the U.S. didn’t join the Allies until 1917. The draft was extended, and the Army went from having tens of thousands of troops to millions.

While theories compete about the flu’s source, there is no argument that it was ravaging the soldiers in Europe in 1917, where the newly expanded American Army was headed.

During their tours, men from around the world, including Americans, lived in tight, squalid conditions that “favored the transmission of influenza. Men moved between camps frequently and went overseas and back, facilitating the transmission of the disease over even wider areas,” wrote Keirsten Snover in her 2008 master’s degree thesis for Eastern Washington University called “The Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919: The Spokane Experience.”

“Because of the war, what might have been a limited epidemic quickly became a pandemic, with troops spreading infection all over the globe,” Snover wrote.

‘Fear of influenza and morbid dread of the disease’

When Anderson ordered the closure of most of Spokane’s public places, there were few who protested, even if most people didn’t believe or understand the danger of influenza. The city streets were “as sparsely filled as in a blizzard,” the Spokesman wrote.

The first day of those quiet streets – Oct. 9, 1918 – Spokane had its first flu death.

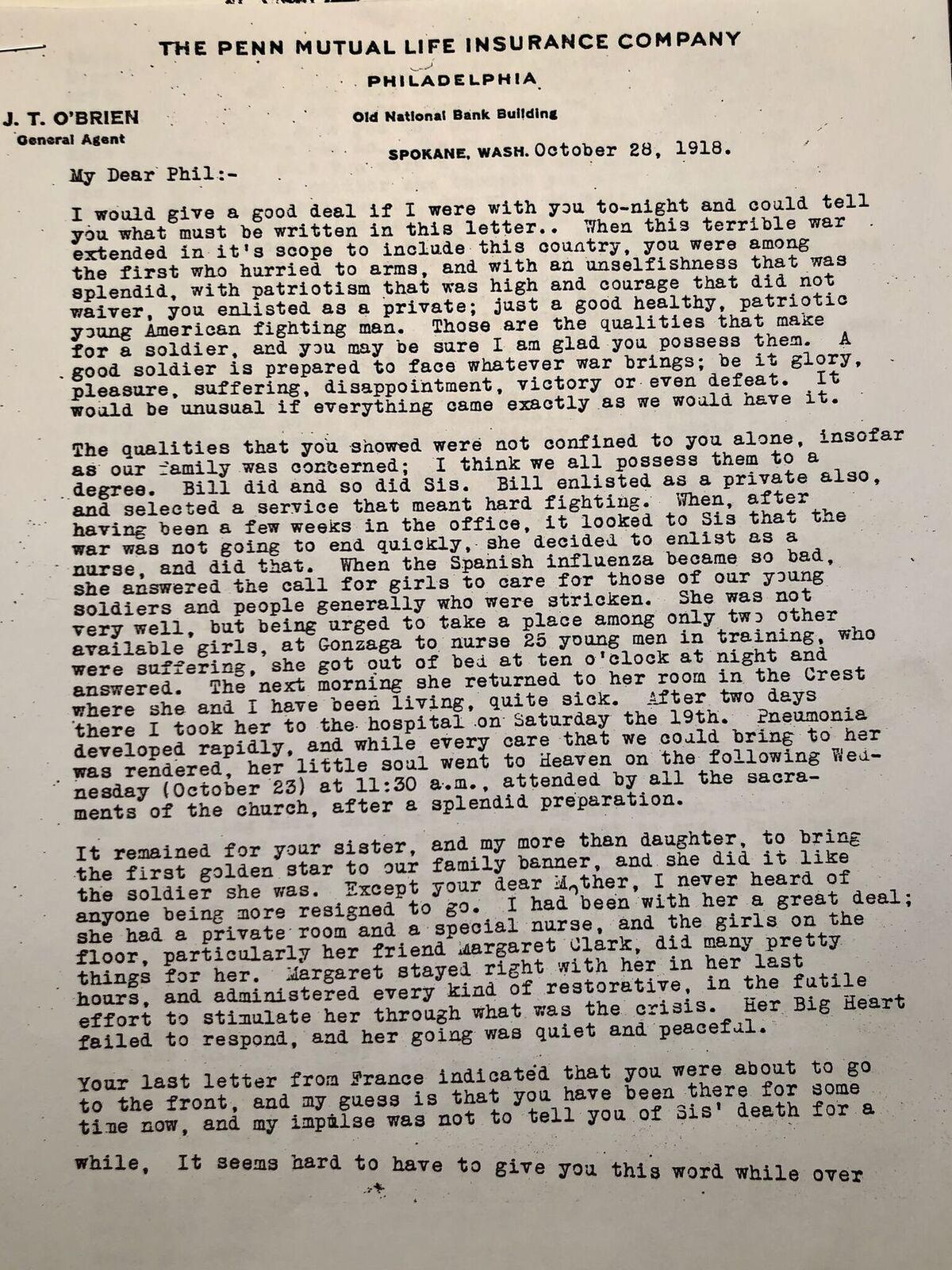

In an article titled “Epidemic grows, girl succumbs,” the Spokesman reported the death of Vera Wood, 17, the daughter of “pioneers of the Sprague region” who lived near the old Spokane University in Spokane Valley. She was “stricken last Saturday,” and contracted the flu from her brother, Vernon Wood, a Lewis and Clark High School student. He recovered, she didn’t.

The cases piled up. By Oct. 10, 1918, there were 220 reported cases of influenza in Spokane and Anderson ordered all doctors in the city to file daily reports with him. The city’s hospitals were at capacity and Anderson saw the situation deteriorating.

Anderson and the local Red Cross formulated a plan to transform one of the city’s hotels into a hospital. Near the corner of Lincoln Street and First Avenue, the Lion Hotel was perfect. It had big and small rooms, and was centrally located near Deaconess Hospital.

On Oct. 16, the city seized the Lion Hotel to convert for people “with severe cases or those who were homeless,” according to the newspaper. The owners objected, and the following day the Chronicle reported Anderson’s indifference to their concerns.

“We don’t care a rap what the owners of the building think about it or about us,” Anderson said. “We don’t propose to haggle with them over it. This is a very serious emergency and if the owners of the Lion Hotel think they can put a dollar in one side of the scale and a human life in the other and get away with it they are very, very badly mistaken.”

It was just the beginning of Anderson’s increasingly belligerent tone against people who disagreed with his public health measures to combat the flu. The number of reported cases was growing by 75 each day, and the total stood at 815 when the Lion became an influenza ward.

Two days later, on Oct. 18, a total of 15 people had died from the flu, and Anderson put Spokane under an even stricter quarantine: gatherings in private clubs were now banned, and passengers on the city’s streetcars were no longer allowed to stand in the aisle and hang on a strap if the seats were full.

On Oct. 23 – just two weeks after the city’s first death – the city had its worst day yet, with 300 new cases reported. Anderson was furious, blaming lax adherence to his measures, and promised to squelch such activities.

“It has been brought to my attention that some people have disobeyed the order by giving private social affairs at their homes,” he said. “Upon the first information I have that such a thing is being planned, we will appear on the scene and arrest the ringleaders without respect to their prominence or social standing.”

Four days later, Anderson was “shocked” to see 1,500 people gather at the Great Northern Depot, site of the clocktower in Riverfront Park, to see young men go off to war. He banned public send-offs of the troops then and there.

“There is a difference between wholesome fear of influenza and morbid dread of the disease,” Anderson told the Chronicle. “Spokane people, for their own good, must realize the difference.”

If he couldn’t get them to fear the disease, he would rule the city with an iron, health-minded fist. He considered shutting the entire city down, except grocery stores and restaurants, but backed off without explanation. Instead, he outlawed Halloween masks, and ordered police to stop masked trick-or-treaters.

‘Small plants called germs’

As a doctor, Anderson was well versed in his day’s theories of sickness and health.

But he, like everyone else in 1918, didn’t know that influenza was a virus, a fact only revealed in 1933 when the human influenza virus was first isolated from a pig. Since its identity as a virus wasn’t yet known, there was no flu vaccine, which only became widely available in 1945.

But Anderson knew about germ theory, and he was happy to explain it to those who balked at his strict measures.

“Spanish influenza is caused by very small plants called germs that come from the mouth or nose of persons suffering from it,” he told the Chronicle. “The person gets the germ into his body by breathing into the nose or mouth the drops or spray that have been sneezed or coughed out into the air by a person sick with influenza or else he gets the germs into his body by putting into his mouth something soiled by the spit of a sick person.”

In a full-page ad in the Spokesman, the city’s health department told people, “Don’t Be Alarmed – Be Careful!” The ad advised people to go to bed if they were feeling sick, keep the windows open, take laxatives and consume milk, eggs and broth every four hours. Nurses were told to wear a mask and wash their hands frequently. Workers were urged to avoid streetcars, walk to work and “eat good, clean food.”

Nowadays, the explanation and remedies seem less than satisfactory, and we have a more nuanced understanding of the so-called Spanish flu.

In short, the influenza virus, like all viruses, is so small and simple it’s not considered a living thing. Instead, it invades living things, and only once it has infected a life form does it replicate. The only identifiable function of a virus is to reproduce, and it will reproduce until the cell it has invaded bursts, sending its millions of duplicates out to invade more cells.

The 1918 influenza virus is called H1N1, which describes the type of proteins that make up the virus, as well as its shape. It’s also called swine flu.

When it struck in 1918, it decimated the usual victims – the very young, and the very old. But it was unusually fatal for healthy adults as well.

In his book “The Great Influenza,” John Barry writes that the immune systems of healthy adults “mounted massive responses to the virus. That immune response filled the lungs with fluid and debris, making it impossible for the exchange of oxygen to take place.”

Instead of saving them, the immune systems drowned their masters.

“Cause of death? That at least was clear: what in a healthy man are the lightest parts of his body, the lungs, were in this cadaver two sacks filled with a thin, bloody, frothy fluid,” Barry wrote.

Despite his odd description of the germ-plants, Anderson showed that he and other medical professionals knew how the virus was spread: through the air and by an exchange of fluids between the healthy and the infected.

War is over

As November 1918 began, the war and flu raged on, and things weren’t looking good in Spokane.

It hadn’t even been a month since Vera Wood died, and the city had tallied 4,000 flu cases and more than 100 dead. There weren’t enough doctors and nurses to staff the city’s many sick wards.

Anderson told the Chronicle the “situation is grave … really serious, more serious than the general public seems to realize.”

On Nov. 4, the state health board issued a new order: Everyone had to wear a mask while out in public, including at stores and restaurants. The masks had to be a certain size – 5 by 6 inches – with six layers of sewn-and-bound gauze.

Two days later, the local Red Cross sold the masks at City Hall. Two types of masks were priced at 5 or 10 cents and all 500 sold out in a half-hour. Hundreds of people were turned away. The Red Cross hastily made 4,000 more masks, but they hung loosely on the face and were unpopular and uncomfortable.

The next day, 800 masks were sold in the first half-hour. The paper tallied the dead at 117.

On Nov. 9, the front-page of the Chronicle screamed in large, bold letters, “Kaiser Quits.” The war was over, at least in Europe. Anderson tried to cool any hearts that may have been warmed by the news.

“Stay home all you can. Order your merchandise over the telephone. Don’t forget to keep your windows open both night and day and keep in the fresh air as much as possible and comply with all rules and regulations,” Anderson said.

He was ignored. With the end of war, celebrations broke out around Spokane on Nov. 11, Armistice Day, including a parade on Riverside Avenue. Thousands of motorists and marchers created a “bedlam of sound” with horns, klaxons, tin cans, streetcar whistles and gongs. The parade, which started at 1 p.m., continued deep into the night. Public parties lasted throughout the day.

More than 4,500 Spokane men had gone to war, and more than 200 had died in the fight. Anderson, fighting to prevent more death, knew he couldn’t stop the celebration, but lamented that the “merrymakers as a rule disregarded the mask rule as a hindrance to their vocal powers.”

The same day, the state health commissioner lifted the mask rule, and news of his ruling reached Spokane that evening and “immediately circulated among a population already in the midst of celebrating the end to the war,” according to the Influenza Encyclopedia, a website with an account of the illness in the city based on newspaper reports of the time.

Anderson, buoyed by peace, said he thought all the restrictions could be lifted soon.

With Anderson – and therefore probably most of the city – believing the flu was on its way out, the Spokesman wrote a fawning profile of the health officer, saying “it is probably fair to say that he has earned the respect and admiration of his fellow citizens in a way no other public official of Spokane has approached.”

Anderson used logic to convince his fellow citizens, the profile said. Failing that, he wielded power.

“Thus, when Wopo, the fruit man, is reported to be shining apples on greasy coat sleeve, Dr. Anderson is likely to reason with him,” it read. “Should the logic of the health office fail the dealer is brought in and an unforgettable lesson administered.”

In the profile, Anderson likens his fight against the flu to the war won in Europe. More to the point, he demanded the power of a general to finally vanquish his “invisible enemy.”

“It is just as necessary to concentrate responsibility and authority in one man here as on the battlefield. Perhaps more so, for the soldier fights a visible foe while the health authorities and the physician are combating an invisible enemy. All we see is results of the foe’s strength,” he said. “The armies of Europe responded at once to unity of command, and the same policy is necessary to success in any undertaking. The reason is that so many situations arise which must be dealt with immediately to secure best results. It is prompt action which saves the day, and we know it as never before after this epidemic.”

Discretion and authority

Dr. Bob Lutz, current health officer for the Spokane Regional Health District, retains the same authority.

According to state law, a health officer, at “his or her sole discretion” can “issue an emergency detention order causing a person or group of persons to be immediately detained for purposes of isolation or quarantine.”

Though Lutz said things would be pretty different today if a flu like the one in 1918 struck Spokane, he acknowledged this authority.

“During times of medical emergency, when population health is of concern, health officers at the state and local level have a lot of authority,” he said. “Isolation and quarantine are elements that are within our purview. They’re not done lightly. Our authority during times of emergency are pretty significant.”

That said, Lutz questioned the effectiveness of social isolation and banning public gatherings. Keeping the sick away from the healthy is important, but the ethics of such a public health decision would also have ramifications.

“They call it social distancing, and it makes a lot of sense, but the science and research hasn’t borne it out to be effective,” he said. “If I isolate someone, because he or she has TB (tuberculosis), from work, it definitely affects the individual. But I have to look at it from a public health standpoint. It’s population first, it’s the individual second.”

Lutz noted that keeping people from school, church or other social gatherings may be detrimental to the individual, and would not be done with the snap of his fingers.

“It would definitely be much more of a conversation than it was 100 years ago,” he said.

It wouldn’t be the only thing Lutz would do differently than Anderson, though he didn’t criticize Anderson’s actions.

“Medicine is a constantly evolving science,” he said. “You do the best you can with the knowledge you have at the time.”

Today, with the advent of vaccines, things are much different, Lutz said. Back then, “serums” were used, giving people a false sense of security.

Vaccines, good hand-washing and the sophisticated surveillance network we have to help identify a virus’ source and path through the population all mean the Spanish flu of 1918 would certainly have a different impact today.

But Lutz didn’t suggest we were safe from such tragedy.

He pointed to the Asian Lineage Avian Influenza, or H7N9, which appeared in China in 2013. While the risk to the public is low, it has killed 40 percent of people it’s infected. Both the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say the virus “has the greatest potential to cause a pandemic,” which is a global disease outbreak that affects a high proportion of the population.

“The WHO is watching it. The CDC is watching it,” Lutz said. “That’s probably the one influenza virus right now that’s on everyone’s radar screen with a potential for a pandemic.”

Theaters revolt

As December began, nothing changed. Every day, 200 cases of the flu were reported. Still, Anderson believed the flu was waning, lifted some restrictions and said school would be in session again, after seven weeks of closure. Theaters were allowed to open, but with strict temperature and humidity controls.

At a time before radio and television, the bored people of Spokane rejoiced. Social life would begin again, just in time for the holidays.

It didn’t last. The flu roared, and the city counted 231 dead. Anderson blamed the war celebrations and recent Thanksgiving gatherings.

“Keep away from crowds,” he said. “Influenza is a crowd disease. The present increase should convince the most skeptical that the gatherings of the Thanksgiving week have been dangerous.”

On Dec. 3, 300 new influenza cases were reported and again the city’s schools were ordered shut. Anderson, the health general, again recommended a full ban on public gatherings, causing a “near-riot” at a city board of health meeting on Dec. 6.

“Hooting, hissing and cat-calling came from the back of the room, and one man had to be cautioned by police Sgt. Daniel to keep quiet or leave the room,” reported the Chronicle.

Facing a would-be mob, Anderson and the board compromised: Churches would be allowed one service each week, but with no singing because it “acts as a releaser of germs during the singing, nearly the same as during coughing, and that would be dangerous.” Theaters could remain open, but would have to “close between the hours of 5 and 7 p.m., to air out the theater building.”

That day, there were 342 new cases of the flu and eight deaths.

Despite the death and disease, business owners were tired of the forced closures, and people were too. The Empress Theater, at Riverside and Browne Street, violated the quarantine. Two health inspectors went to the theater and found “84 people standing in the lobby, in direct violation of the quarantine order,” Anderson said. There also were children under 12 in attendance and the gallery was overcrowded. When the health inspectors ordered the lobby cleared, “management paid no heed.”

If the Empress tried to reopen, Anderson said he’d arrest the manager, the ticket seller, the doorkeeper and every other employee.

Later that week, with deaths tallied at 374, the owner of the Hippodrome on Howard Street said he was closing the theater for good, and blamed the financial losses stemming from the quarantine.

The next day, Dec. 17, a coalition of theater owners said they had collected several thousand signatures asking for the end of the ban on public gatherings.

“Those petitions will have as much effect on me as water on a duck’s back,” Anderson said. “The people circulating and signing the petitions might just as well save their ink.”

He said the partial ban would go on until January and suggested the businesspeople were putting profits ahead of the public good. “A dollar is good, but it is no good to a dead man,” he said.

Around this time, Anderson outlawed Christmas and New Year’s celebrations.

Forget all about the flu

Over the next few weeks, the situation improved. The worst was over. On Dec. 30, Anderson announced all restrictions would be lifted at noon New Year’s Day, and schools would reopen Jan. 2.

Even Anderson’s rhetoric shifted.

“Forget all about the ‘flu.’ Dismiss it from your mind,” Anderson said, according to the Jan. 4, 1919, paper. “I believe everybody would be better off if they would just forget all about the ‘flu.’ I don’t mean by this that people should mingle with persons who have the disease, but I do mean that people should get away from the idea that if they have a little pain or ache they should think it is the influenza. Just quit thinking about it as much as possible. This is my suggestion.”

On Jan. 13, Anderson closed the Lion Hotel hospital, which “truly signaled the end of Spokane’s epidemic,” according to the Influenza Encyclopedia. Over 89 days, the hospital had treated 617 people and saw 68 deaths.

Between October 1918 and February 1919, some 11,000 Spokanites got the flu – 11 percent of the population. The severity of the disease in Spokane led to a higher death rate than in Seattle. And its three “peaks” – two in October and one in December – were more than the typical American city, which saw just two.

The number of cases and deaths would grow outside of this October to February window, but Anderson wouldn’t stay in Spokane to see it all the way through. Deaths would continue to mount after February 1919, but at a slower rate.

On April 18, Anderson was given a farewell reception by the employees of the city health office and members of the Rivercrest Contagion Hospital, according to the May 10 edition of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

He was retiring as the city’s health officer after eight years, and had been named the state commissioner of health.