This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: ‘Determinants of health’ can come down to the neighborhood

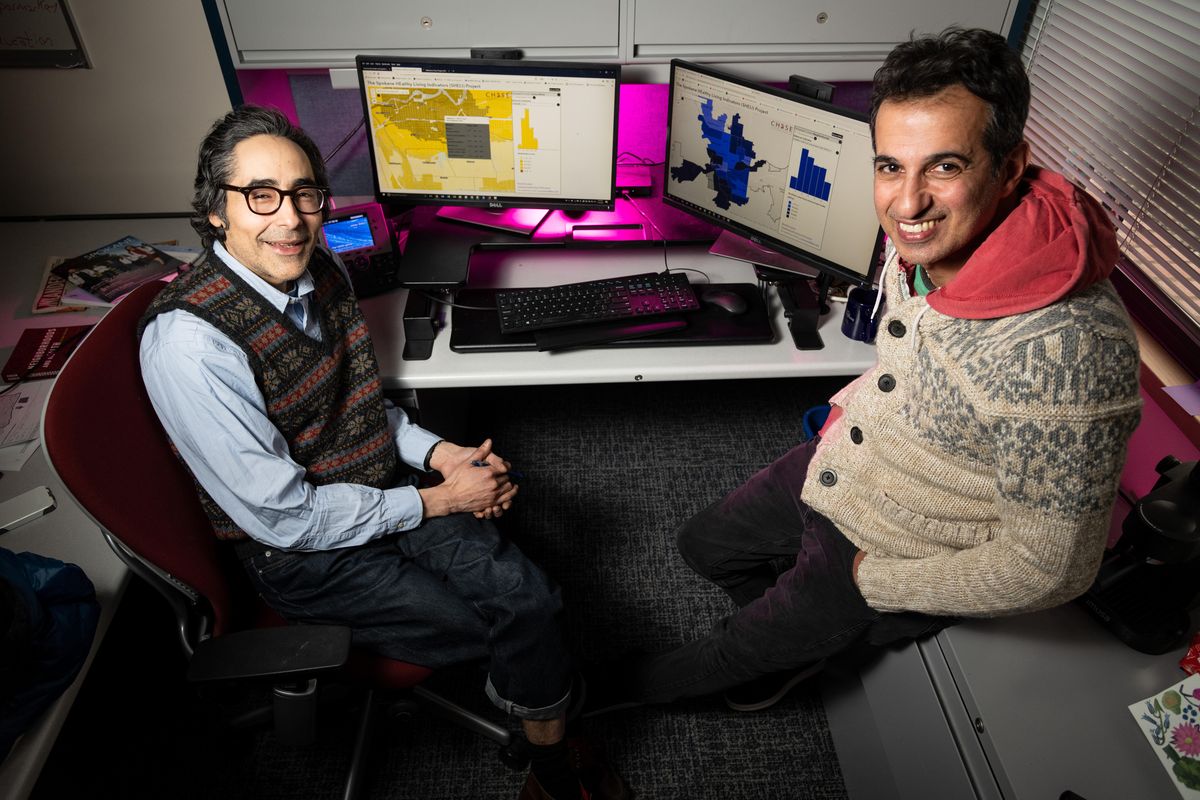

Dr. Pablo Monsivais, left, and Dr. Ofer Amram demonstrate the Spokane Healthy Living Indicators (SHELI) online tool on the Spokane campus of WSU’s Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine. (Colin Mulvany / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Where you live can have a big influence on your health.

If it’s easier to get a hamburger than a head of lettuce, that has an effect. If you’ve got to drive to the nearest grocery store, but can walk to 15 places where the fryer baskets never stop sizzling, it has an effect. If the nearest health clinic is across town, it has an effect.

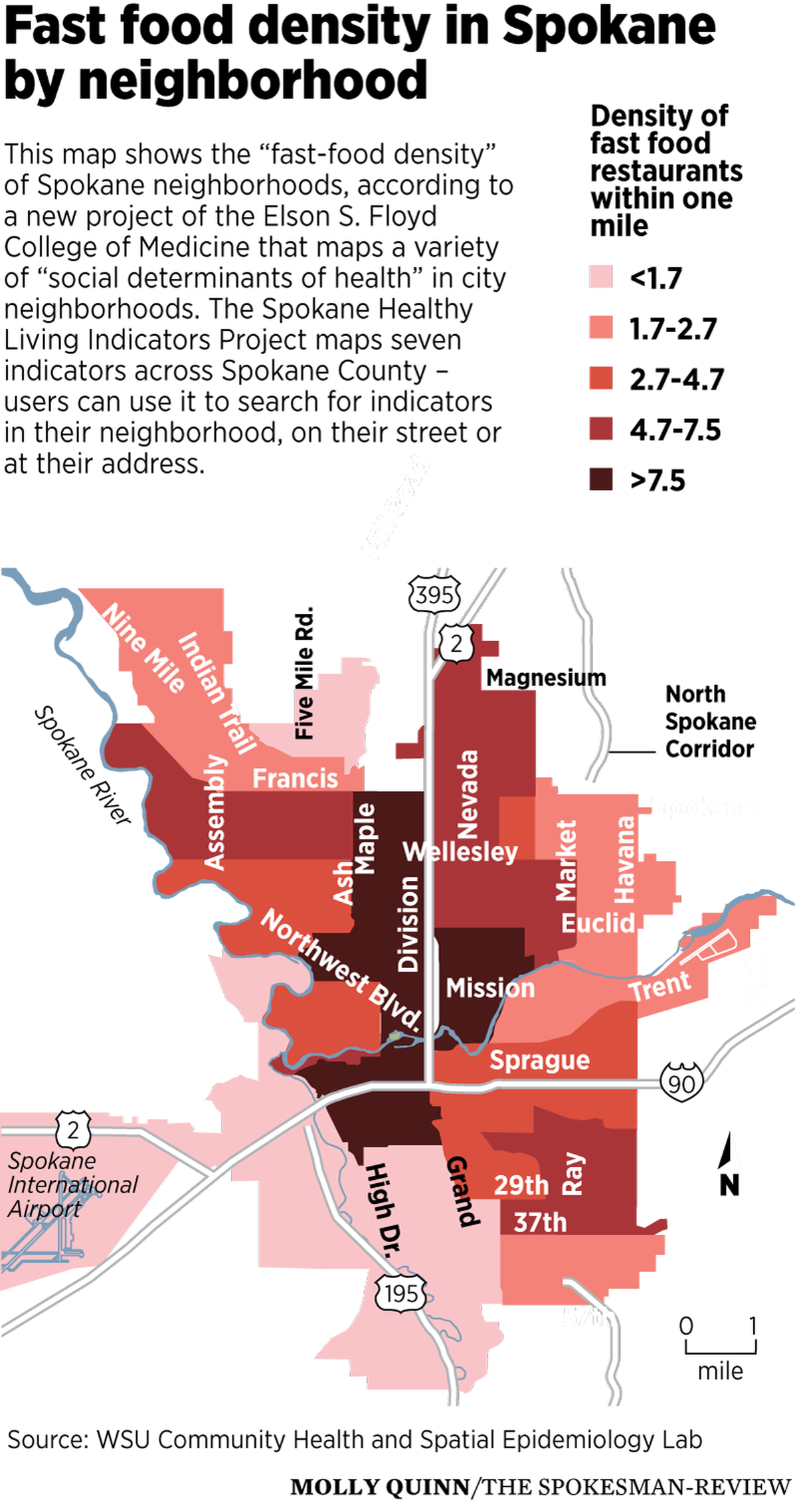

You can quantify these associations – the neighborhoods in Spokane with the most fast-food restaurants, such as Emerson Garfield, have shorter life expectancies than those with many fewer fast-food restaurants, such as Rockwood. The highest obesity rates correlate with the longest distance to grocery stores.

One must be cautious of such correlations; they tell us a lot about a population’s health broadly, but can’t account for all the factors in any individual’s life or choices. But such associations between a neighborhood’s “social determinants of health” and the general well-being of its population are the subject of increasing interest to those who study and promote public health.

A new project by an associate professor at Washington State University’s Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine is beginning to map some of those factors for Spokane at a very granular level, with a new online tool that makes it possible to examine differences between neighborhoods on a variety of measures.

The Spokane Healthy Living Indicators Project is a continuation of the work that associate professor Pablo Monsivais began during his six years on the faculty at the University of Cambridge, mapping food access across Great Britain.

“I thought, ‘I don’t know Spokane very well, but one thing I do know is everywhere I’ve ever lived or worked, neighborhoods are really different,’” Monsivais said this week. “They shape or limit our activities. They shape the food choices we make. They shape whether we drive or walk or ride a bike.”

The SHELI project went online last week. It provides data on seven categories, including the density of fast-food restaurants within a mile, the availability of doctors and dentists, access to supermarkets and walkability. You can look at the information by neighborhood – or drill down all the way to your own address.

For example, I live in the Cliff-Cannon Neighborhood. When I look at the neighborhood characteristics, they show a relatively high density of fast-food offerings within a 1-mile radius, at 7.8 for the neighborhood on average. That’s primarily because it’s close to downtown – the Riverside Neighborhood – which has by far the highest concentration of such restaurants, at almost 22 within a 1-mile radius.

But the tool also can bore in much more closely, to the street or address level. Taking Cliff-Cannon as an example, when you drill into the street level, you see that density of fast-food joints varies depending on how close to downtown you are, as you would expect. And when I put in my own house, which is roughly in the center of the neighborhood, I get my personal fast-food density: 17 within a 1-mile radius.

There are also two grocery stores within walking distance, plenty of doctors nearby and a decent walkability score, at least compared with other parts of town.

SHELI doesn’t link these figures to health outcomes. But earlier research conducted by the Spokane Regional Health District examined the differences in health among Spokane’s neighborhoods, and found stark differences. That research, a 2012 report called Odds Against Tomorrow, found that life expectancies varied dramatically among neighborhoods – the average life span varied by more than 18 years between the city’s shortest life expectancy (66.17 years in the downtown Riverside district) and longest (84.03 in Southgate on Moran Prairie).

It found, on measure after measure, from unemployment to obesity to maternal smoking to cardiovascular disease, that different neighborhoods were like different worlds. Perhaps unsurprisingly, people in the poorest neighborhoods had worse health – and more unhealthy behaviors – than those in wealthier ones.

Monsivais said he was partly motivated by the research in Odds Against Tomorrow to carry out the SHELI project. His goal is that it becomes a tool for public officials and activists to try and develop policies that might improve the health of local residents, and he plans to add information to the tool as he gathers feedback.

“What I want to do is basically grow it with input from these groups, these stakeholders,” Monsivais said. “We want it to be basically a dialogue. What does the community want to know about the environment that is shaping their health?”