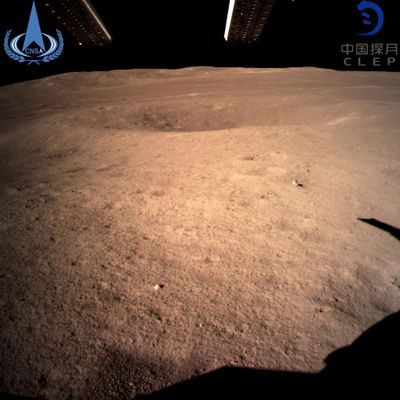

A new space power is born as China lands on the far side of the moon

When China announced on Thursday that it had successfully landed on the far side of the moon, it wasn’t just a scientific breakthrough. To Beijing, its expanding space mission also carries an increasingly powerful symbolic message.

“This is more than just a landing,” said Alan Duffy, a lead scientist with the Royal Institution of Australia who focuses on space exploration. “Today’s announcement was a clear statement about the level of maturity that China’s technology has now reached. Beijing’s longer-term goal to match U.S. capabilities could now become reality within two decades, and on the moon within perhaps only one decade.”

From a scientific standpoint, Thursday’s announcement surprised some who had expected the endeavor to fail. Landing a spacecraft on the far side of the moon, which never faces Earth, hasn’t been done before because its location makes direct radio signal communication impossible. But Chinese researchers were able to overcome this challenge by launching a relay satellite to communicate with the Chang’e 4 spacecraft and its rover.

Although nobody could be certain that the mission would succeed, the broader ambitions were clear from the beginning. Chinese officials did not publish a date for the landing in advance and kept details of the mission in secret, but the mission was long planned. In fact, it was decades in the making.

“It’s been a long-term vision of the Chinese,” Duffy said. In the early 2000s, few would have guessed that China would become such a major player in space so quickly, given that it had long shown little or no interest in gaining a foothold. When Beijing finally sent its first astronauts into orbit in 2003, Western observers dismissed the news as a probably pointless effort to play catch-up with the United States and Russia.

But as China continued to expand its operations, enthusiasm for space explorations was weakening in the two countries with the most successful programs. Adjusted to inflation, NASA’s budget has declined in some years, while Russia became busy financing President Vladimir Putin’s military operations abroad.

In China, the opposite was happening. Long before it made global headlines for its top-notch space endeavors, China launched early preparatory missions as early as 2007 to examine the surface on the far side of the moon and later to identify possible landing sites.

In some ways, the Chinese program already matches U.S. capabilities, even though it still has far less funding. Last year, China scheduled over 40 space mission launches, more than twice the number of those in 2017. Although the rapid Chinese progress may be surprising given its program’s financial shortcomings, researchers say that the country deliberately focuses on prestige projects that will speed up its recognition as a top space power.

“China makes very visible advances, but they don’t operate scientific missions in such depth as NASA does, for instance,” Duffy said. Moon missions appear to be especially valuable to Beijing, and the country has made progress on that front far more quickly than in other, less prestigious realms.

In a white paper published in December 2016, China made some of its most important missions public on its own, including the now-successful moon landing, several planet flybys and a Mars landing that’s scheduled for 2020. Those missions, Beijing has maintained, all serve peaceful purposes.

“The white paper sets out our vision of China as a space power, independently researching, innovating, discovering and training specialist personnel,” read a news release accompanying the 2016 white paper.

But those assurances failed to convince the Pentagon, which asserted in a report last August that China’s space program was “central to modern warfare.” Although NASA works closely with Russia, U.S. lawmakers have banned similar projects with the Chinese space agency over espionage fears.

In August, Vice President Pence announced plans to create a “Space Force” military command by 2020 and specifically cited an incident involving a Chinese satellite as a key reason to expand efforts in space. As it was seeking to leave a mark about a decade ago, China opted to blow up one of its own weather satellites in a 2007 military test in low Earth orbit. The destruction created so many particles that its remnants still account for about 25 percent of today’s space debris, posing growing risks to satellites and space missions of all nations.

Thursday’s announcement might be threatening U.S. leadership in space – but not in the same way as in 2007.

“It’s more about prestige,” Duffy said.