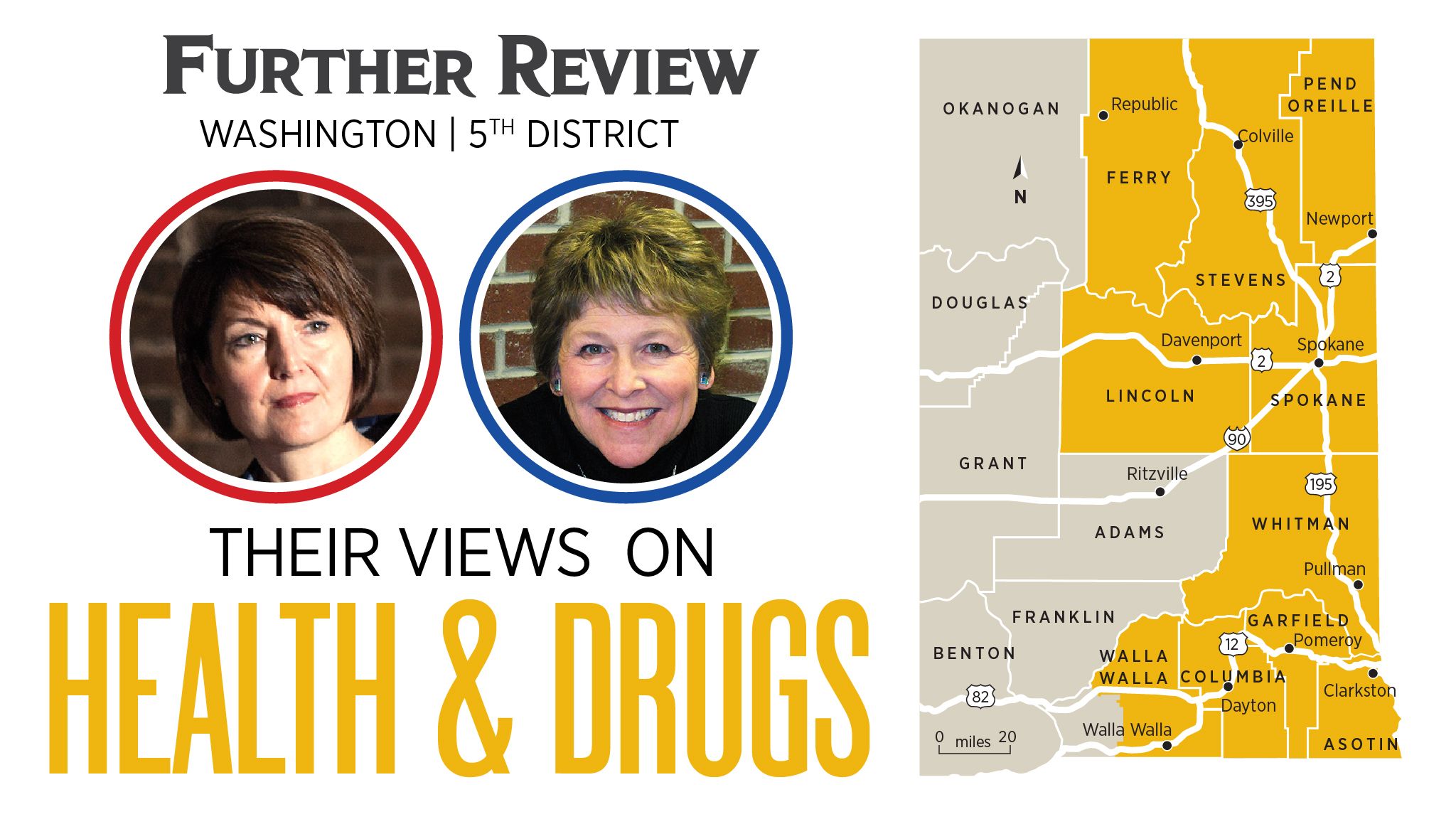

Where they stand: Cathy McMorris Rodgers, Lisa Brown give stances on marijuana, opioid addiction treatment and drugs

Across America and in Eastern Washington, federal drug policies will affect a fledgling marijuana industry and the region’s response to the sharp rise in opioid addiction.

U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers said in a recent interview she was open to states experimenting with their own policies surrounding marijuana, a softening of her previous stance on the drug that was legalized by Washington voters in 2012. Lisa Brown, her Democratic opponent for Eastern Washington’s seat in Congress, would push those policies further, and blames Republicans for standing in the way of medical research that could lead to therapeutic cannabis uses for vulnerable populations, including military veterans.

The same year Initiative I-502 passed in Washington state with 56 percent of the statewide vote (52 percent in Spokane County), the congresswoman said she didn’t support legalization of the drug, citing public safety concerns. Since that time, marijuana has become a $1 billion-plus annual industry in Washington, and state regulators have set up a system of oversight for medical sales.

“We get to see the laboratories of democracy at work,” McMorris Rodgers said in an interview last week. “I continue to have concerns about especially recreational marijuana, and the impact it may have on children.”

The congresswoman said she needed more information before making a decision whether to support legislation that would change the legal classification of cannabis under federal law. She previously has opposed reclassifying the drug. The Drug Enforcement Administration lists marijuana as a Schedule 1 drug, the most stringent category of enforcement for substances found to have no medicinal value. Other Schedule 1 drugs include heroin and LSD, while other street drugs like methamphetamine and cocaine have less stringent restrictions than cannabis.

There have been many attempts in Congress to change that classification at the federal level as more states legalize markets, but so far none has attracted enough support for a vote. Brown said she supports several pieces of legislation that would ease restrictions on the drug, including a House bill introduced by Ohio Republican Rep. David Joyce that would allow state law to trump the federal classification if a legalized market has been established.

“That makes sense to me,” said Brown, who was the state Senate’s majority leader in 2012 when lawmakers in Olympia opted to let voters decide if recreational marijuana should be legal, rather than weighing in themselves. “There are a lot of public safety issues that I know Washington state has dealt with. Safety with respect to growing, packaging and marketing.”

Both candidates said they were skeptical of the decision earlier this year by U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions to rescind the Justice Department’s legal guidance on the drug, a four-page memorandum issued in 2013 by then-Deputy Attorney General James Cole that indicated federal law enforcement would allow states to enact their own policies on the drug, as long as it didn’t find its way into the hands of minors or its trade supported other criminal enterprises.

“I lean against that,” McMorris Rodgers said. “Although, it’s important to recognize that we still have legal suppliers of marijuana, and those that are not abiding by the law. We need to make sure that we are enforcing the law.”

Brown said she opposed rescinding the memo, noting the legislation she supports would make the so-called Cole memo settled federal law. She said Congress should instead be taking up legislation that would increase access and research for medicinal marijuana, particularly for military veterans. She supports two bills that would allow doctors at Veterans Affairs hospitals to provide counseling on marijuana use and collect data from patients using the drug.

McMorris Rodgers has in the past voted against legislation that would allow VA doctors to talk about marijuana for medicinal use.

Addressing opioid deaths

During Kellyanne Conway’s stump speech for McMorris Rodgers last week at a private fundraiser in Spokane, the senior White House official blamed the media for failing to cover comprehensive legislation passed by the House of Representatives addressing deaths from addiction to opioid drugs, both prescribed by doctors and illicit substances such as black market fentanyl, heroin and other narcotics.

“If you don’t know, there was money in there for school safety and for the opioid crisis. Higher than what has ever been allotted in our nation’s history,” Conway said. “You’re not getting the information, it’s not being covered.”

McMorris Rodgers touted that legislation, a hodgepodge of nearly 60 pieces of bipartisan laws that change the way Medicare and Medicaid work, enabling access to treatment and doctor consultation for opioid abuse and calls for new prescription labeling standards by the Food and Drug Administration for opioid drugs, as well as providing funding for treatment facilities. It passed the House of Representatives with 396 votes, including a vast majority of both Democrats and Republicans.

“The opioid package in the House has been one of the biggest priorities in the House this year,” McMorris Rodgers said.

The Senate is expected to pick up the legislation before the end of the year, according to the congresswoman’s office. The large package included a bill sponsored by McMorris Rodgers that would allow Medicare recipients to participate in medication therapy programs intended to reduce the risk of painkiller overdose.

Those kinds of services that go beyond the doctor’s office, or treatment center, are necessary to combat the problem of opioid addiction, said Misty Challinor, with the Spokane Regional Health District’s Opioid Treatment Program.

What is also needed is long-term guarantees of funding, because those experiencing opioid addiction need long-term care that includes the use of drugs like methadone, said Linda Graham, the health district’s policy analyst.

The health district does not endorse any specific legislative proposal, and officials stress that the most effective strategies would involve addressing issues such as mental health, childhood trauma and other factors that are shown to correlate with use of illicit drugs.

Legislation proposed by Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Rep. Elijah Cummings would tackle the rise in overdose deaths in the United States in a similar manner to how Congress tackled the HIV/AIDS crisis in the early 1990s. It would call on Congress to set aside $10 billion annually over the next decade in competitive and formula grants for local and state governments to spend on treatment programs, research for nonopioid painkillers and access to the anti-overdose drug naloxone.

Brown said that although she supports the House’s legislation addressing opioids, she prefers the Warren-Cummings approach which calls for dedicated amounts of spending on the issue.

“Without funding we aren’t really going to get to the heart of the crisis,” Brown said. “It’s kind of a hollow promise without funding.”

The continuing resolution passed earlier this year to fund the government dedicated $4 billion to addressing opioid deaths. However, Congress would have to reauthorize that program moving forward, whereas the Warren-Cummings bill sets minimum funding levels for the next 10 years.

That legislation, however, doesn’t identify where the money would come from in a federal budget that is facing mounting deficits. The formula established by the HIV/AIDS legislation has led to increasingly higher budgets for that program since its inception, with the total amount spent increasing by a factor of 10 between 1991 and 2017 to more than $2.3 billion annually.

Supporters say the bill would eliminate the stigma against those who are addicted to painkillers and illicit drugs, in much the same way the HIV/AIDS legislation sought to change the public’s perception of those experiencing the disease. That’s also the mission of the health district’s treatment program.

“Our staff get here at 5:15, and our clinic opens at 5:30 a.m. because we have such a large group of individuals that work at 6 a.m.,” Challinor said. “Most people would have no idea that they were on a program, because they look like you and I.”

Breastfeeding, needle exchanges

Brown and McMorris Rodgers agreed on the importance of breastfeeding, as well as maintaining the status quo on funding for a local program that provides clean needles for those injecting drugs.

Concerns were raised this summer after it was reported the United States was pushing back on a resolution by the World Health Organization supporting breastfeeding. The New York Times reported in July that opposition was fueled by lobbies supporting infant formula companies.

Both candidates said they supported the United States’ continued efforts to “protect, promote and support breastfeeding,” as stated in the WHO resolution. Brown said breastfeeding saved lives and was healthier, while McMorris Rodgers pointed out that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said reports about the basis of opposition to the resolution were inaccurate. The issue prompted President Donald Trump to tweet that the United States supported breastfeeding, but wanted to make certain that lower-income mothers had access to formula.

They also agreed that federal funding should not be brought in to support the needle replacement program that is currently run out of the Spokane Regional Health District. Five days a week, users of injection drugs can exchange used syringes for sterilized replacements, as well as receive information about safe injection habits in an effort to curb the spread of communicable diseases like HIV and hepatitis.

The program has been in existence for 27 years in Spokane County. Initially challenged by local law enforcement, the county prosecutor and the state’s attorney general, the Washington Supreme Court unanimously ruled in 1992 that the program fell within the local health district’s authority to stanch the spread of infectious diseases.

The needle exchange does not accept any federal money to support its efforts, despite changes in a 2016 congressional spending bill that would allow for coverage of program costs beyond the purchase of sterile needles. The state’s health department is in charge of allocating $2.6 million in state funding annually to support the 26 needle exchange sites statewide.

Brown said she believed local control of the program was working well and didn’t need federal interference. McMorris Rodgers said she wouldn’t support federal dollars going toward purchasing needles.