Dedicated workers help adaptive climbing take off in Spokane

Emily Stevenson was depressed.

The Gonzaga student hadn’t slept well in three years. The rigors of her engineering school work threatened to overwhelm her.

“Sleeping wasn’t a thing for me in freshman and sophomore year of college,” Stevenson said.

So a counselor recommended she do something that was fun, physical and that would give her a sense of accomplishment.

Stevenson took up rock climbing. For a year, she went to Wild Walls, Spokane’s first climbing gym.

“It was awesome,” she said.

She slept better. Her depression ebbed. School eased.

This was far from a sure outcome because Stevenson, along with roughly 3 million Americans, is blind.

Wild Walls didn’t have a program for blind climbers, or any climbers with disabilities. But Phil Sanders, a long-time employee and climbing instructor, offered to work with Stevenson whenever she wanted. The two would climb during quiet times of the day with Sanders yelling instructions up to Stevenson.

“She went from not being able to do one climb in a day to being able to do 10 routes in a day,” Sanders said. “We figured out a fun system for guiding her up the wall.”

As climbing has exploded in popularity, the question has increasingly become how to make the sport available to more people.

In Spokane, that effort has mostly been done by individuals such as Sanders. A new organization hopes to coordinate those efforts.

On Oct. 26, the Inland Northwest Adaptive Climbing Initiative will formally launch with a presentation by Craig Demartino, a professional adaptive climber and motivational speaker.

The goal of the initiative is to make experiences like Stevenson’s the norm, not a lucky exception.

Climbing, Demartino said, is a perfect adaptive sport because it forces focus.

“It’s one of the few sports that really gets them into the flow state where they’re really focused on what they’re doing and they’re not focusing on their disability,” he said. “When you’re climbing, you’re not worried about the chronic pain you have, or the PTSD. All of a sudden, you’re just focused on the next 3 feet in front of you.”

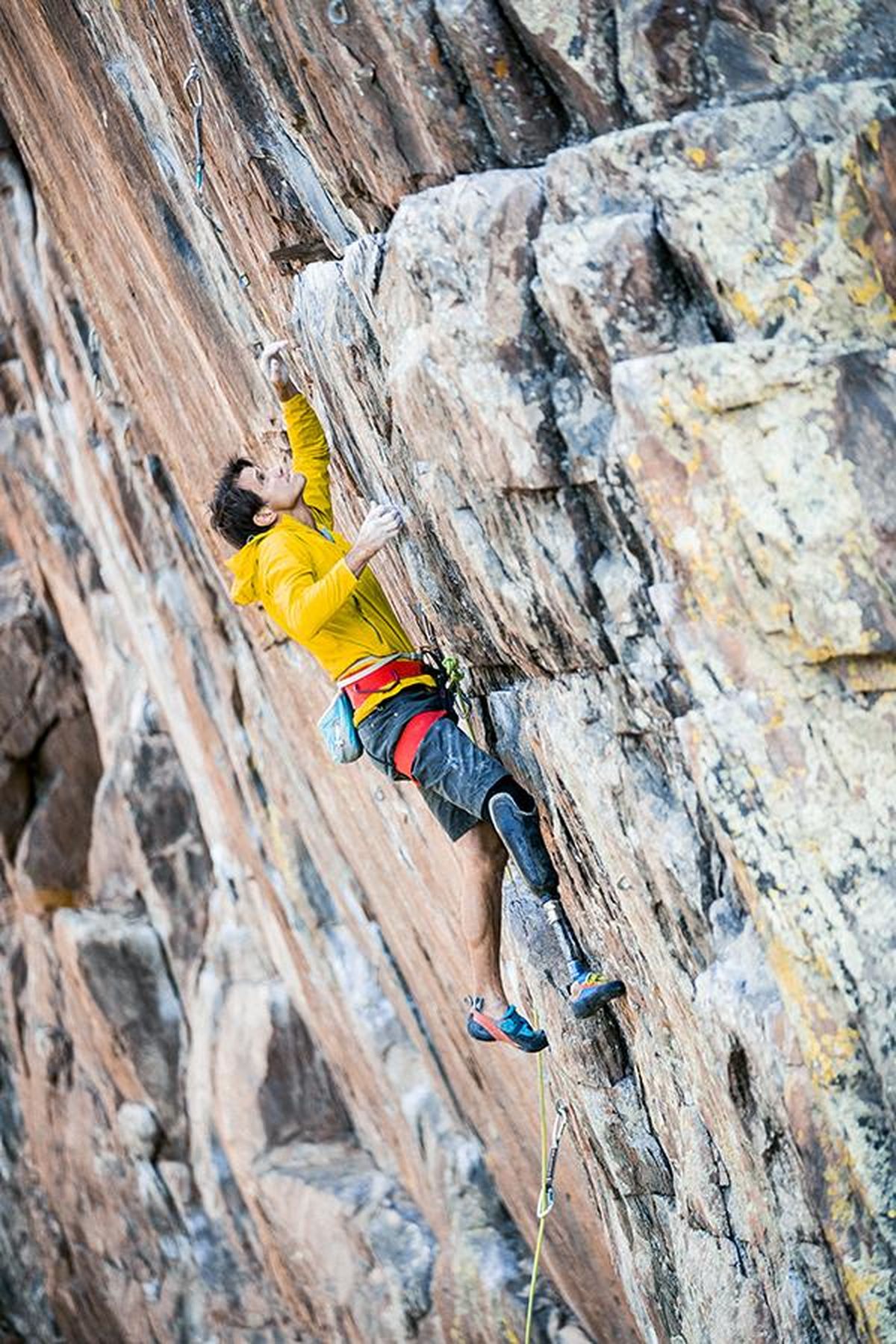

Demartino lost his right leg in 2002 after being dropped 100 feet while climbing in Colorado. People rarely survive falls from that height. Demartino broke most of the bones in his legs and parts of his back. He was in the hospital for months. Doctors wondered if he’d walk again, much less climb.

Eventually, he did. It took years to overcome the physical pain and fear of roping back up. But now he climbs with a prosthetic and tours the country speaking and teaching people how to make adaptive climbing work in their gym. Demartino works for Adaptive Adventures.

He was also part of the first unsupported all-amputee ascent of El Capitan. He was also the first amputee to Climb El Capitan in less than 24 hours.

Adaptive climbing isn’t the most common adaptive sport, but Demartino said the benefits of it outweigh the potential challenges. Plus, it’s good physical therapy.

“Climbing was one of the few things that stretched me out and made me feel good again,” he said.

The Inland Northwest Adaptive Climbing Initiative is hosting Demartino. He will also spend two days at Wild Walls teaching regional climbing instructors how to use adaptive climbing gear in a gym setting.

The newly created Inland Northwest Adaptive Climbing Initiative’s goal is to promote adaptive climbing in the Spokane area and help coordinate between different universities, climbing gyms, parks departments and organizations. The effort is also being supported by the parents of a Spokane climber who died in Germany in 2016. Donations to the Derek Kiehn “Accessibility for Outdoor Adventure” memorial fund, via the Innovia Foundation, will go toward adaptive access.

The goal of the initiative is to coordinate the existing facilities and efforts, said organizer Robin Redman, a champion of adaptive sports in Spokane and one of the primary drivers behind the initiative

“In three years time, we should not even have a meeting,” she said.

The Spokane Rotary Club 21 purchased specialized adaptive climbing gear that will stay at Wild Walls.

Zach Turner, the climbing gym manager at Eastern Washington University, has been slowly introducing adaptive climbing to the EWU gym. He said that started about a year ago when Jeremy Weaver came to the gym and said, “Hey, I want to climb.”

Weaver has limited use of his legs because of cerebral palsy, a neurological disease, and has been using a wheelchair since he was 16.

Creating systems that work for Weaver has been “a learning curve” Turner said. Adaptive climbing requires special rope systems and, in some cases, special harnesses.

“The biggest thing is the individual specific needs of each climber,” Turner said. “Everyone is different. Before anyone comes and climbs, we try and figure out what they need.”

Redman reached out to Turner and Sanders and helped send them to adaptive climbing trainings through Paradox Sports.

Turner and Sanders hope future adaptive climbers can simply show up at their gyms and find whatever they might need to get climbing.

“My personal goal is to make adaptive climbing not adaptive climbing, but make it regular climbing,” Sanders said.

For Weaver, climbing has been nothing but positive. He started doing pull-ups using a fixed rope, but now he’s at the point where he can climb a top rope (with some rope assistance) using his legs and arms.

Weaver hopes that adaptive sports, particularly outdoor recreation, will continue to grow in Spokane. He plans to climb outside for the first time next summer.

“It allows me to work on my range of motion,” he said of climbing. “I’m still not to the point where I can walk again. I might not ever be to that point. But the feeling of using my entire body again is fantastic.”

(509) 459-5508

elif@spokesman.com