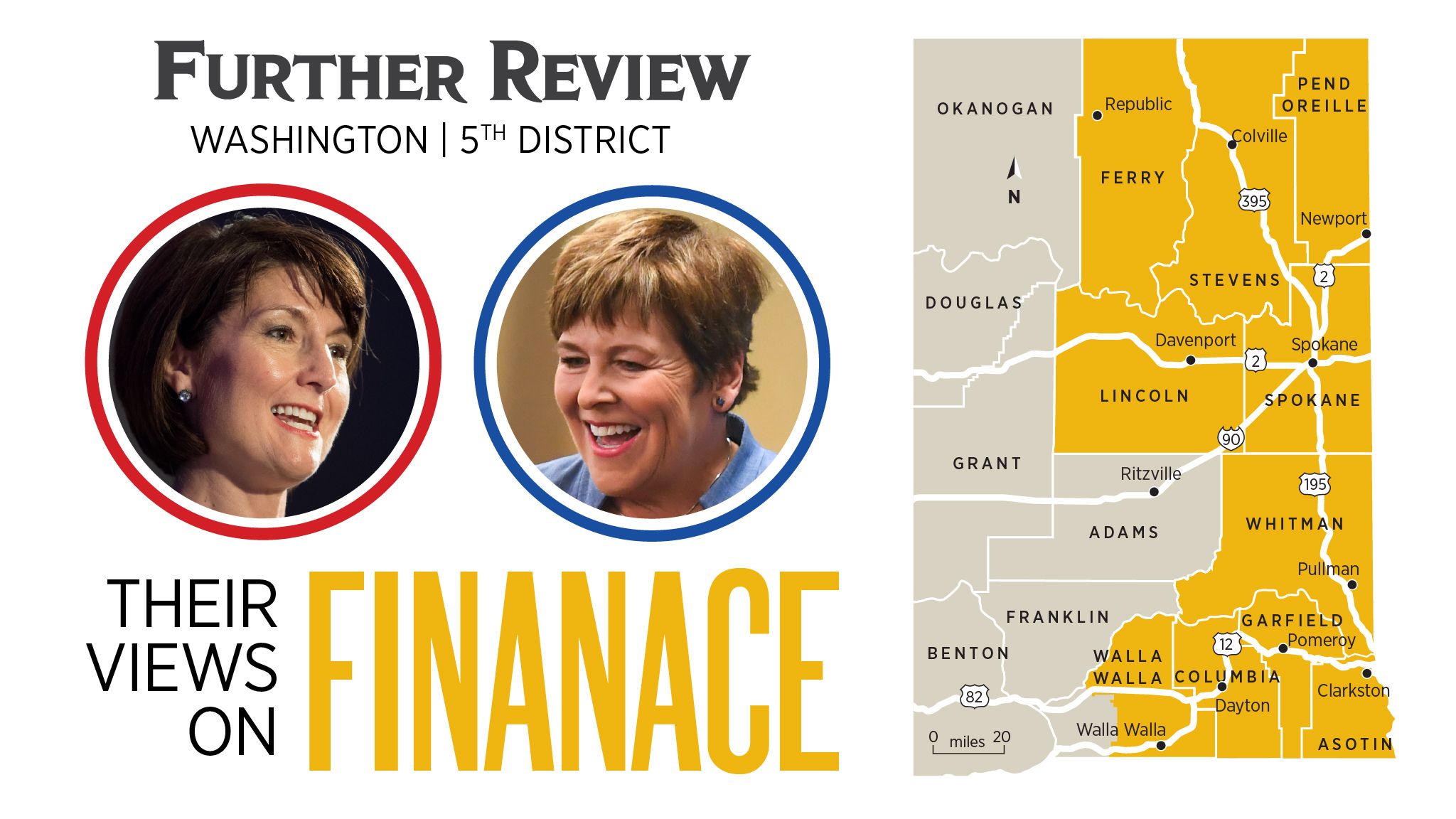

Where they stand: Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, Lisa Brown on taxes, trade deals and the budget

Last year’s exclusively Republican-crafted tax reform legislation has driven a wedge between the two women vying to represent Eastern Washington in Congress.

For Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, the legislation has been her largest campaign rallying cry. The seven-term congresswoman points to dropping unemployment rates, wage increases and rising optimism among business owners as evidence the GOP slashes in government revenue are helping Americans. Lisa Brown, her Democratic challenger and a former economics professor, has called the legislation fiscally irresponsible amid estimations lower tax payments will cause the ballooning national debt to continue to swell, to the tune of $1.5 trillion over the next decade.

McMorris Rodgers said last week, in a wide-ranging interview on fiscal matters including the debt, taxes, federal funding for higher education and international trade, that the Republican Congress would push for what’s being called “Tax Reform 2.0,” a bill that would extend the lower tax rates for individual ratepayers past its current 2026 sunset date. The legislation later passed the House of Representatives with the support of just three Democrats, and it’s unlikely the Senate will take up the issue before the midterm elections.

“It will give certainty to individuals that they will have those rates in the future,” the congresswoman said.

Early scoring of the bill by Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation, a nonpartisan group of financial experts on Capitol Hill, found that the legislation would cut revenues $545 billion in just three years ending in 2028. Democrats, among them Brown, have argued that the bill will put pressure on Congress to cut spending on federal programs to help balance the ledger with less money coming in, but McMorris Rodgers has denied that’s her plan.

Brown called the introduction of the individual tax cuts now “a gimmick” intended to cloud the full cost of the bill.

“If you take one decision like that, it’s easy to say yes. Why were they made temporary in the first place?” Brown said.

The GOP made a reduction of corporate tax rates permanent in their tax bill last year, while it sunset the individual rate reductions, as part of a parliamentary move to ensure that only a simple majority of both chambers of Congress would be needed to pass the bill. The legislation passed Congress and was signed by President Donald Trump without a single Democratic vote.

Brown said in an interview the law had “dramatically expanded the national debt.”

“They were trying to avoid the financial fiscal consequences of the bill,” she said.

McMorris Rodgers has countered that those fiscal consequences for voters have been lower unemployment, higher wages and increased growth in the gross domestic product. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported earlier this month that average hourly wages have increased 2.9 percent nationwide in the past year, which conservatives have said is evidence firms are reinvesting in their employees as a result of the tax breaks. At the same time, the consumer price index – the cost of goods and services paid by most Americans – increased 2.7 percent, meaning the purchasing power of those wage increases were largely offset by the rising costs of food, housing and medical care.

The McMorris Rodgers campaign also pointed to rosier revenue forecasts from the Washington Office of Financial Management, released last week, to indicate economic growth was on an uptick as a result of the tax reforms. Planners added an additional $348 million to their revenue projects between 2017 and 2019.

Brown said she doesn’t support the type of “supply-side economics” the Republican tax cuts were based upon – that is, a reduction in tax revenue from individuals and businesses would spur economic activity that could keep pace, or surpass, the mounting federal deficit. The idea prompted many of the tax policies of the administration of President Ronald Reagan, the effects of which are still disputed by today’s economists due to other economic factors, including adjustments to federal interest rates, a repeal of certain tax cuts for businesses and several subsequent votes to raise taxes.

“It didn’t work. I still don’t believe that supply-side economics will reduce the deficit,” Brown said. “It’s not the philosophy I would advocate for.”

Brown said she also believed Washington state should not institute an income tax as a sole way of making its tax system more fair. As leader of the Senate majority in 2009, Brown floated the idea of a tax on income exceeding $250,000, one of many possible suggestions intended to make up a state budget shortfall caused by the economic downturn. She said this week she never supported an income tax on its own as a way to make the taxing system more fair.

“The kinds of a proposals that were being talked about were lowering business and occupation taxes, capping sales taxes,” Brown said “They were big picture blueprints for how you would create a new, more fair tax structure.”

McMorris Rodgers, who served in the Washington House of Representatives from 1994 until her election to Congress in 2003, said she also didn’t support a state income tax, noting Washington voters had shot it down multiple times.

Trade deals, tariffs and higher education

Both candidates expressed interest in giving Congress more control over presidential prerogatives on trade and returning the country to multilateral deals that Trump has said he doesn’t support.

They were interviewed before Trump announced Monday a new trade deal with Canada and Mexico. In a statement Monday, McMorris Rodgers praised Canada’s decision to join the deal and said she’d be reviewing it more closely for effects on Eastern Washington’s agricultural commodities.

Brown said she supported legislation drafted by Republican Sen. Bob Corker, of Tennessee, and co-sponsored by seven Democrats and eight Republicans that would require Congressional approval when the president imposes a tariff to protect “national security.” Trump cited those concerns as a reason for announcing sweeping tariffs on steel and aluminum from Canada, Mexico and Europe this spring.

“I believe that the executive branch, and specifically the Trump administration, is using the national security exemption inappropriately and broadly,” Brown said.

McMorris Rodgers said she was “generally supportive” of the idea and pointed to actions Congress already took to insert itself into the trade process through legislation passed during the administration of President Barack Obama.

“The last time we passed trade promotion authority, Congress was increasing our role,” McMorris Rodgers said, referring to a 2015 law that put new requirements on the White House when submitting trade deals to federal legislators for approval. “I have supported that effort.”

The 2015 law set up negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a multilateral trade deal in Asia and the Pacific from which Trump withdrew the United States soon after taking office. The decision prompted an outcry from Washington wheat farmers, who worried the lack of a deal with some of their largest foreign customers would send them elsewhere for their grain.

Both Brown and McMorris Rodgers said the administration made the wrong choice pulling out of the deal. Brown said she’d want the U.S. to have a seat at the table to negotiate a new agreement with multiple countries, an approach she prefers to Trump’s trade policy of one partner, one deal.

“I support an aggressive return to multilateral trade agreements for agriculture with Asian countries,” Brown said.

McMorris Rodgers, who had been critical of some aspects of the deal in the negotiating stage, said it still represented the country’s best counterpunch to Chinese influence in the Pacific market.

“I thought TPP was one of the best ways to counter China’s continued dominance, especially in the Asia-Pacific region,” the congresswoman said.

The two candidates have sparred in advertisements and statements on the role of the federal government in assisting students, with McMorris Rodgers pointing out that tuition in the state’s public institutions more than doubled in the years Brown was leading the Senate’s majority. Brown has countered that the federal government has a duty to increase its assistance for higher education students to match what it has been in years past.

Pell grants are the most direct way the federal government assists with education. The maximum amount a qualifying student can receive to aid their education has been set in recent years by Congress as part of their appropriations for education and health services. As part of the 2011 spending bill, that amount had been tied to inflation, but it expired in 2018. Congress, as part of the spending plan for this year, increased the maximum amount by $105, to $5,920, but that increase isn’t guaranteed in the next round of funding.

The candidates’ response to the federal grant question reflects the positions they’ve taken on education funding. McMorris Rodgers said lawmakers could look at tying the cap to inflation, which would mean additional federal spending would keep pace at least with the price of consumer goods. But rising tuition costs also should be explored and countered, something that takes place at the state level for public institutions, she said.

“That takes the pressure off the students and federal government,” McMorris Rodgers said.

Brown said the least the federal government could do is tie the maximum amounts to inflation.

“What would be even better, would be to peg it to return back to an earlier time when they covered more of the cost of education,” she said.

Balancing the budget

In April, Congress voted for the second time in seven years on a proposal to amend the U.S. Constitution to require the federal government to approve a balanced budget.

The vote was just several months after the approval of the tax reform bill, and its $1.5 trillion price tag. The vote prompted hawkish members of the Republican Party to suggest hypocrisy within their ranks, with Rep. Mark Meadows, chairman of the House’s Freedom Caucus, telling national newsmagazine Politico, “There is no one on Capitol Hill, and certainly no one on Main Street, that will take this vote seriously.”

McMorris Rodgers said the vote, which earned a majority of support in the House of Representatives but failed to reach the two-thirds majority needed to pass as a Constitutional amendment, represented a commitment to rein in spending in future budgets.

“It would force Congress to start making the tough decisions, and start living within our means,” the congresswoman said. If the law were in place when the tax cuts were passed, Republicans would have had to couple their tax plan with matching spending cuts, or convince a three-fifths majority of the chamber that the debt limit should be increased to match the loss of revenue, according to the terms of the legislation.

Congress has made similar votes in the past not to subject certain pieces of legislation to a law calling for automatic spending cuts if deficits increase past a certain amount. Republicans called for that vote after enacting the tax reform legislation last year.

The amendment, like the separation of the corporate tax cuts from the individual tax cuts in the Republican tax reform, amounted to “a gimmick,” Brown said.

“I think if someone wants to balance a budget, and they have a majority of the House and Senate and the president, then pass a balanced budget,” she said.

Both candidates served in the Washington state Legislature, which at the time of their service did not have a law requiring a balanced budget. Lawmakers subsequently approved one beginning in 2013.