Spokane was a stop for George H.W. Bush before, during and after his presidency

If George H.W. Bush was the type to hold a grudge, he certainly could’ve held one against Spokane, which passed him up twice for the presidency in 1988, first in the Republican caucuses by going for televangelist Pat Robertson, and then in the general election, by going for Democrat Mike Dukakis.

But Bush wasn’t. And he didn’t. Less than a year after winning that election with no Electoral College help from Washington, Bush came to Spokane bearing gifts of bipartisanship and a tree.

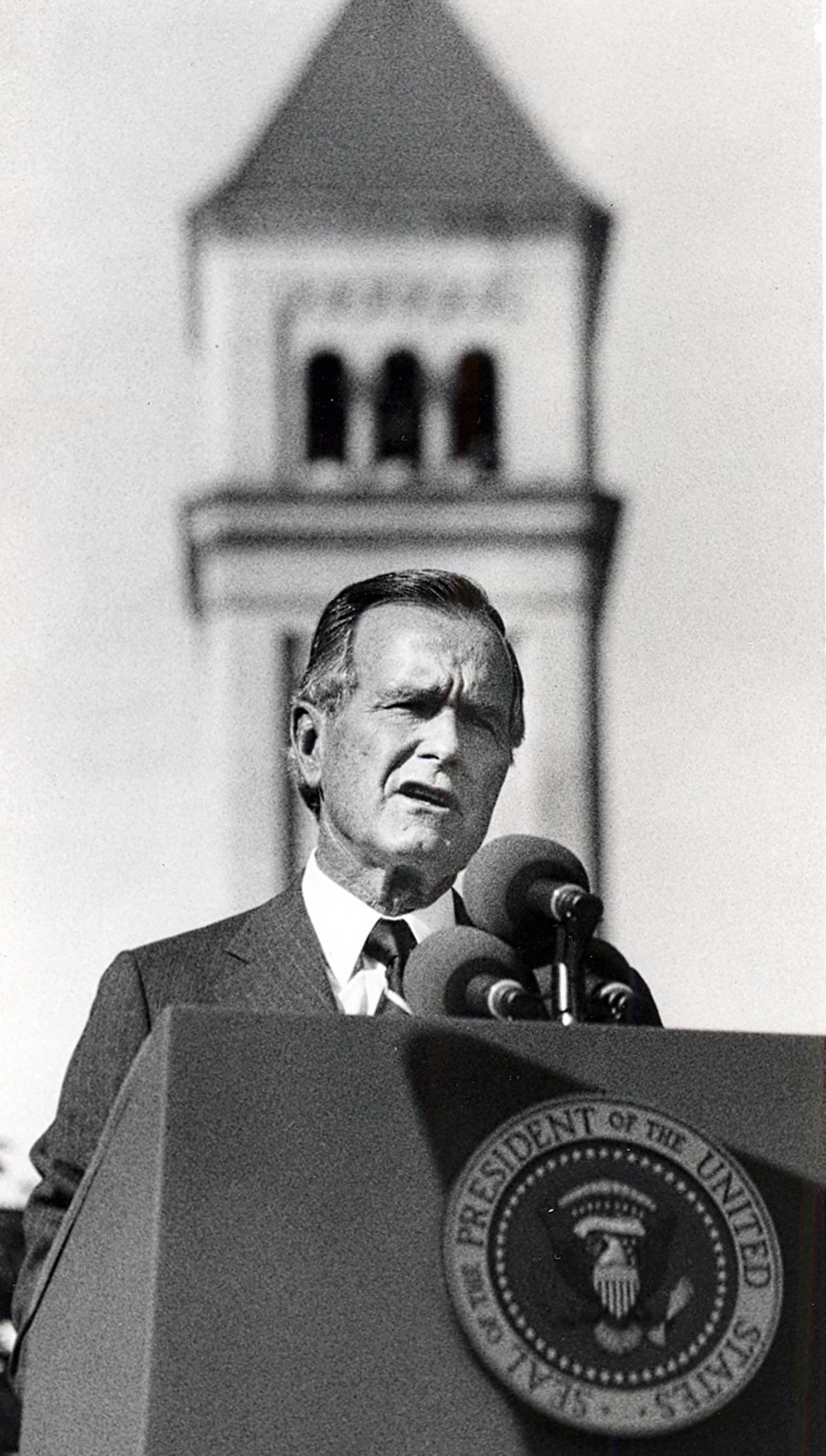

The new president appeared with new House Speaker Tom Foley, in Riverfront Park, marking the state centennial and the 15th anniversary of Expo ’74. Although the historic record isn’t perfect, it was thought to be the first time the president of one party appeared with the speaker of the opposite party in the speaker’s hometown.

It wasn’t Bush’s first visit to Spokane, or even his first visit to Riverfront Park. The former president, who died Friday at age 94, stopped in the city before, during and after he was president.

In 1980, George Bush – no one paid any attention to his middle initials then – made a campaign speech on the floating stage in Riverfront Park. It was early October, about a month before the election, and the former U.N. ambassador, former CIA director, former ambassador to what was then called Red China, had joined Ronald Reagan on the GOP ticket about two months earlier.

Jimmy Carter and the Democrats were “the party of despair” while Reagan and the Republicans were the “party of hope and prosperity.” In a sign he knew his regional audience, he promised that Reagan would get rid of the Russian grain embargo if they were elected. A month later, the Reagan-Bush ticket won Washington handily, turned the governor’s mansion over to Republican John Spellman and helped GOP Attorney General Slade Gorton beat Sen. Warren Magnuson.

Bush came back in October 1984, again on the campaign trail, for a rally at the old Davenport Hotel. The rally speech was standard, praising the economic successes over the previous three years and dismissing Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale as “gloomy.”

In a post-rally interview, however, Bush showed his range as a candidate, fielding regional questions like the proposal to sell off the Bonneville Power Administration – he didn’t think it would happen – and national questions like the prospect of Reagan doing better in the upcoming debate after having a terrible showing in his first face-off with Mondale.

Reagan may have been overloaded with facts and figures during preparations for the first debate. For the second, he’ll change strategy to be himself.

“He’s an awfully good debater, say I, having been done in by him. And I’m a pretty good debater,” Bush said, making a compliment out of what might have been the beginning of the end of his presidential hopes in 1980, a debate in New Hampshire that catapulted Reagan to victory in the nation’s first primary and the road to the nomination. Even though he had denounced Reagan’s proposed supply side economics as “voodoo economics” during the primaries, Reagan eventually chose him as his running mate and Bush was a loyal member of the administration.

The Reagan-Bush ticket captured Washington again in 1984, but without the coattails. Four years later, Bush was seeking the nomination, promising to continue many of the administration’s policies but calling for a “kinder, gentler nation.”

He didn’t have a clear field, facing Kansas Sen. Bob Dole, televangelist Pat Robertson and others in the early primaries and caucuses. Washington Republicans picked their nominee through the caucus system then, and energized evangelical Christians flocked to the caucuses for Robertson in Spokane and around the state.

Washington’s delegation to the 1988 Republican convention was dominated by Robertson delegates. It was at that gathering that Bush uttered two of his most famous statements: Describing the country as “a thousand points of light” and promising to tell Congress “Read my lips, no new taxes.”

Four days after the convention, Bush was again in Spokane, again at Riverfront Park, for a rally on a hot August afternoon. He, his wife, Barbara, and a group of children rode the park train, the Spokane Falls Choo-Choo, to the stage where he talked of patriotism, being strong on defense and tough on drugs, and repeated the “Read my lips” line. The crowd joined him in the refrain. He promised to clean up the environment but steered clear of the biggest regional environmental issue of the time, the problems with nuclear waste at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation.

Spokane was a busy crossroads for the campaign that year. His opponent Michael Dukakis came to Spokane a few days later, and a few days before the election. Dukakis won the city. Bush won the county and most of Eastern Washington. Dukakis won the state. Bush won the White House.

Nine months after taking office, Bush made another trip to Spokane and Riverfront Park for a show of bipartisan comity with Foley and the Democratic Congress. Arriving on Air Force One, Bush brought an elm sapling that had come from a tree at the White House planted by John Quincy Adams.

The two “planted” the tree – actually they shoveled a bit of dirt into a pre-dug hole – in the park near the newly opened Centennial Trail, and weaved calls of clean air and water with the celebration for the state’s 100th anniversary of statehood and the 15th anniversary of the environmentally themed world’s fair that gave birth to the park. An estimated 20,000 people attended the ceremony.

The night before, Bush and Foley had dined with a few others at Patsy Clark’s restaurant in Browne’s Addition. Bush paid the tab with a check, but after he left co-owner Tony Anderson said he was going to frame it and put it on the wall rather than cash it.

When Bush read about that in The Spokesman-Review the next morning, he sent the cash to cover the bill and a tip to the restaurant before he left town, with an additional note to thank the waitress who had explained she had no idea she’d be serving the president until she showed up to work that night.

For his 1992 re-election campaign, Bush got a challenge in the Washington precinct caucuses from conservative television commentator Pat Buchanan but easily won the state’s delegates. By the summer he was locked in a three-way race with Democrat Bill Clinton and independent Ross Perot.

That September, he flew into Spokane International Airport, then helicoptered to Colville, for a rally at the Vaagen Bros. Lumber Co. in front of a crowd of about 7,000. He promised cheering mill workers, loggers, their families and neighbors he’d work to change the Endangered Species Act to put them ahead of the spotted owl as the nation tried to solve the region’s timber problems.

It was a campaign stop tailor-made for the evening news shows, with Bush speaking from a podium of freshly milled timber and a well-loaded logging truck in the background. But it wasn’t that well-researched by the campaign’s advance team. There never were any spotted owls in the nearby Colville National Forest. At one point in his speech, Bush referred to Forks, Washington, a community that was hard hit by the spotted owl rules for old-growth timber, as “not far from here.” Forks is about 445 miles from Colville.

Bush carried Stevens County and some of Washington’s rural counties. Clinton took Spokane County along with much of the Puget Sound and won Washington on the way to the White House.

As a former president, he returned to Spokane in 2000, a proud father campaigning for his son. It was just days before the election, and days after a story broke about George W. Bush having a 1976 conviction for a DUI.

“Four days before the election? Come on,” the elder Bush told the crowd, adding that George W. had apologized for his mistakes and would “restore the honor and respect the presidency deserves.”

Somewhat freed from the heavy policy speeches of a candidate, he got laughs with some one-liners, including a dig at Democratic candidate Al Gore and reports that he’d raised money during a visit to a Buddhist temple, by framing it as a “compliment” to running mate Joe Lieberman. “The thing I like about Joe is he gives to the temple. Very different than Gore.”

He explained he was campaigning without his wife, Barbara, who was back home in Texas “hopefully not going too ballistic” before the election. The mention of her name brought a roar from the crowd, which brought an expression of mock surprise from Bush.

“I was president for heaven’s sakes,” he joked.