Filipino veterans to receive Congressional Gold Medals for WWII service

Sitting at the kitchen table of his South Hill home, Keith Ermitano has a million and one stories from his childhood living in the small town of Hilo on Hawaii’s Big Island.

Horse riding, eating apples planted by German immigrants, getting 50 cents from grandma for a movie that only cost a nickel. Back then, before the tourists came and crowding followed, life was easy, he said – the type of easy that’s effortless to look back on and impossible to replicate.

But growing up, there were some stories he never got to hear. Especially those about World War II.

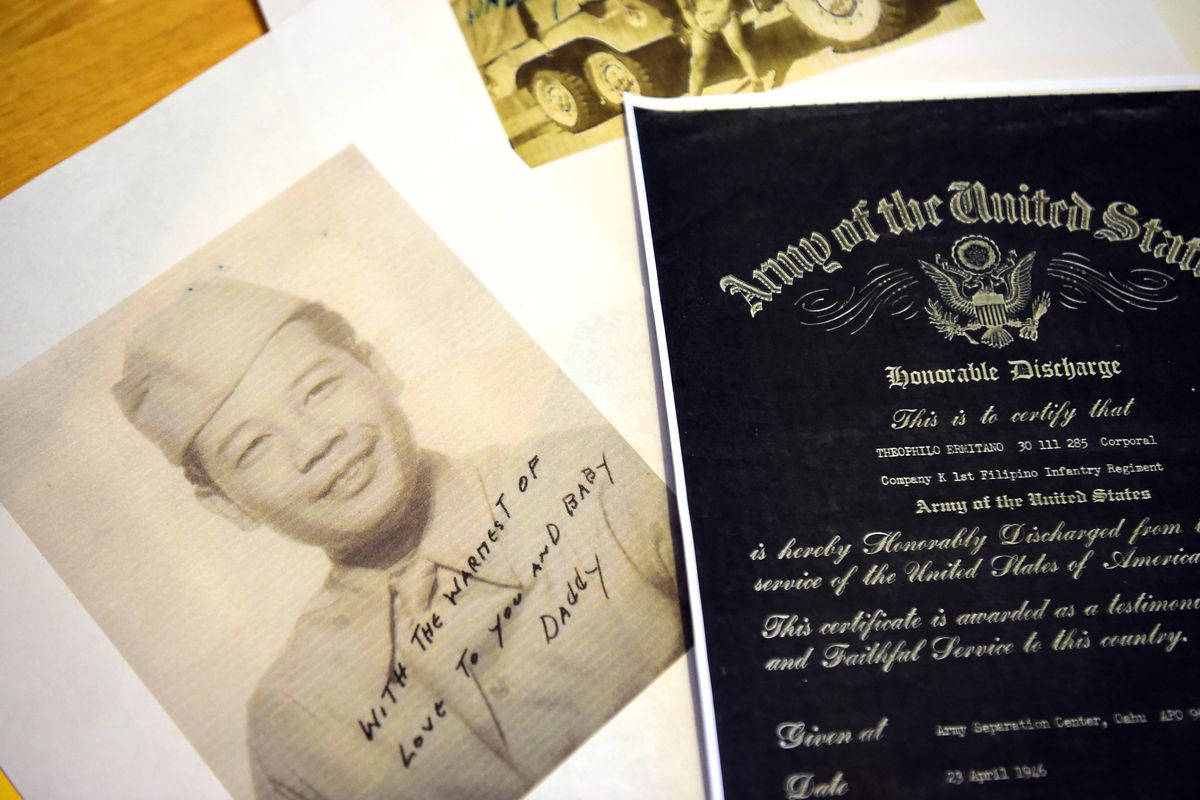

His father, Theophilo Ermitano, who died at 92 in 2012, was a member of the 1st Filipino Infantry Regiment in the U.S. Army. And from 1944 to 1946, he fought against the Japanese in the Philippines, sometimes in deadly guerrilla-style warfare.

The younger Ermitano has no idea what his father did in the war or on which of the dozens of islands he did it. His questions on that subject would usually get a cold shoulder in response.

“He never talked about it,” the younger Ermitano at 73 years of age said. “He was quiet.”

That’s all likely to change this weekend. On Saturday, Ermitano will be in sunny Oahu, the third-largest Hawaiian island, where he and hundreds of others will receive Congressional Gold Medals – a recognition effort by the U.S. government for Filipino veterans’ service in World War II.

There, he’ll have the opportunity to meet a handful of veterans still alive. Maybe some will tell him about what they did. Perhaps they’ll know his father. At the very least, they can tell him what it was like.

“I can’t wait for Sunday, to see how many people will be there,” he said.

Shortly after the war, President Harry Truman reluctantly signed into law the Rescission Act of 1946, which rescinded any veterans’ benefits that would have gone to Filipino troops in the war. Congress argued that the Philippines was a U.S. territory, and the money spent after the war should go to the mainland United States and its citizens.

Jon Melegrito, the executive secretary of the Filipino Veterans Recognition and Education Project that started in 2015, said the law is still in effect, though there have been some concessions from the federal government.

In 2009, President Barack Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which provided $200 million to Filipino veterans in the form of a tax-free $15,000 for each of the veterans who are U.S. citizens and $9,000 for noncitizens.

Still, Melegrito said many Filipino veterans and their families never received the recognition they deserved for fighting in the war.

“They bravely fought with loyalty to the American government,” he said. “We ought to honor that.”

In 2015, his group successfully lobbied Congress to pass the Filipino Veterans of World War II Congressional Gold Medal Act. Last year, a group was invited to Washington, D.C., where House Speaker Paul Ryan presented the awards to the handful of Filipino-Americans who could make the trip.

“It’s a step in the right direction, but we still have a lot of work to do,” said Melegrito, who lives in the D.C. area. “We won’t stop until the original act is rescinded and we can restore dignity to these veterans.”

Ermitano said his father ticked all of the boxes of a classical stern head of the household. He was quiet, worked hard labor in the sun, and for most of his life, smoked cigarettes.

“He loved smoking,” he said. “He smoked all the way till he died.”

The older Ermitano lived most of his life in the same area of Hawaii, where he met a local, had a couple of kids, and settled down.

Ermitano said back then, post-traumatic stress disorder wasn’t a thing. And men didn’t talk about what haunted their minds.

But what his father would share of the war was often frustration. Mostly over the lack of appreciation.

“It’s about time,” Ermitano said of the medal. “Woulda been nice if dad was alive to get it, though.”

If he were alive today, Ermitano said it might be the first time his father was proud to be a veteran.

It’s why, rather than travel to a ceremony closer to home, or have the medal shipped, he chose Hawaii. It’s where his memories remain, the good and the bad.

And it’s where his father remains, stories and all.

“I wanted to go home because that’s where my dad is from,” he said. “That’s home.”