Steve Christilaw: What in the name of Tommy John is going on?

There are moments that make you just plain feel old.

I was chatting the other day with someone who shall remain nameless and, for whatever reason, I mentioned Tommy John.

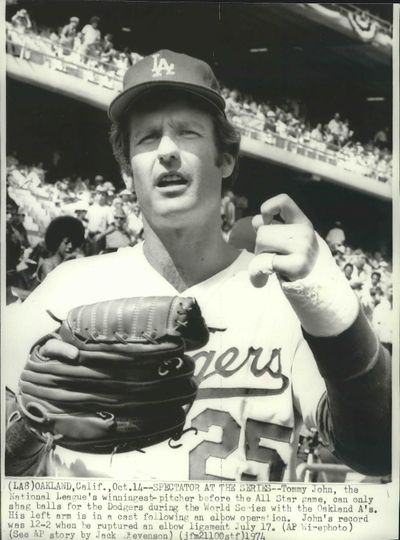

Now I will grant you that Tommy John is a name that goes a ways back, but he can’t have vanished into the foggy haze of memory yet, can he? I still have his baseball card as a young lefty pitcher for the Chicago White Sox, one from his breakout season with the Dodgers and tons from his great run with the hated New York Yankees. I can still picture his straight-out leg kick and delivery in my mind’s eye as clearly as I can see … OK, more clearly than I can see something right in front of me these days.

But, while I am writing this on yet another birthday morning that features a crooked number I never planned on reaching when I was a kid (who does, really), I never considered T.J. to be a name relegated to distant history.

But there it was, a strange look from the whippersnapper to whom I was talking. “Do you mean the surgery or the underwear?”

Silence.

So, apparently, along with having to explain to the grandkids who Sir Paul McCartney, John Glenn and George Carlin were, there is yet another name in need of some grandpa-splaining when it comes to certain members of my family.

It’s just that, in those moments of silence, I suddenly feel so much older.

Before there was the underwear, before there was the surgery, there was the pitcher.

There are pitchers who are flamethrowers. They still talk about how Steve Carlton’s slider would perform an optical illusion on the way to the plate – they called it “an exploding slider” because it would arrive at the plate before your eye could adjust to it and “explode” through the strike zone.

Randy Johnson, especially early in his career, made a catcher’s mitt pop with a sound few others could match. It was like hearing fireworks on the Fourth of July.

Tommy John wasn’t one of them. His fastball could barely break the speed limit on a Montana interstate.

I wish I could remember which play-by-play announcer coined the term “crafty left-hander,” but it was a tailor-made description for Tommy John. If he tossed you a bottle of sunscreen, it would dart and dash two or three times on its way to you.

I have always loved lefties.

Sandy Koufax was done before I was too aware of baseball.

I was an early fan of the Baltimore Orioles, and while I loved watching Jim Palmer work, the two that impressed me most were the lefties in that rotation: Dave McNally and especially Mike Cuellar.

McNally was tough and gritty and the perfect pitcher to have on the mound in a must-win game. Cuellar? Cuellar was the guy you wanted on the mound if you wanted to mess up an opponent’s swing.

Guys like Cuellar and John were consummate pitchers – not just throwers. I would swear they never threw the same pitch at the same speed twice in the same game and never in the same at-bat. And they could make the ball move and dart in any direction at any time – and there are more than a few hitters who claim they could make it deliver a classic Bronx Cheer as it missed their bat.

John’s elbow didn’t hold up however. At least his ulnar collateral ligament didn’t. After a dozen years in the big leagues, it looked like he was through – and that was a shame because he was with the Dodgers and having a great season.

But a Dodgers team doctor was a pioneer and he had an idea.

And then the legendary Dr. Frank Jobe performed an experimental surgery that harvested a ligament from the forearm and grafted in as a replacement for the damaged one.

To say the least, it changed the world of baseball forever.

T.J. went on to play another 14 years in the majors, never missing another start. Since then, the surgery named after Tommy John has salvaged more careers than the spitball. In fact, Tommy John surgery has become commonplace.

And that bothers the man for whom the procedure is named.

You see, a lot of the patients receiving the graft are too young – too young to see the kind of damage to a joint that he had. Well over half (57 percent) of all such procedures are done on teenagers between the ages of 15 and 19.

And that appalls both Tommy John and his son, Tommy John III, a chiropractor with a solid sports medicine background.

The younger T.J. has written a book: “Minimize Injury, Maximize Performance: A Sports Parent’s Survival Guide.” In it he argues that youngsters, especially gifted ones, are encouraged to overperform – in essence to throw too much, causing degenerative damage to their body.

Young ligaments need time to develop and grow strong. Throwing a baseball might look natural to those of us watching from the sidelines, but it places a massive strain on an elbow, especially when players try to throw breaking balls. Overuse, the Johns say, is the root cause of the epidemic of UCL replacement surgeries.

School teams put a hard cap on pitchers. You throw X number of pitches and you are done for X number of days. Still, whether it’s the lure of a scholarship or the lure of a potential major-league career, there are too many kids throwing way, way too many pitches. And it’s damaging their underdeveloped elbows.

Teenagers shouldn’t routinely need to have the ligament in their throwing elbow replaced before they leave high school, in other words.

The Johns, father and son, are now devoted to traveling the country to urge parents to let their kids play multiple sports. That, they say is a key to preventing overuse injuries in kids. Throw baseballs, sure, but shoot basketballs, too. Or wrestle. Play golf, tennis. Run cross country.

Develop as a more well-rounded athlete.

I think that’s great advice.

You won’t get that from a pair of boxer briefs.