Spokane school zone speed cameras snare 21,500 motorists, net $4 million in fines

FILE - Longfellow Elementary School crossing guard LaCrisha Loper cautions students before assisting them across Nevada at Empire, June 14, 2016, in Spokane, Wash. A camera installed near the school tracking speeders has resulted in nearly 16,000 citations issued since the beginning of 2016. (Dan Pelle / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

The final bell has rung for the school year, but Spokane city officials are already gearing up for a tougher fall of speed enforcement on roads near the city’s schools.

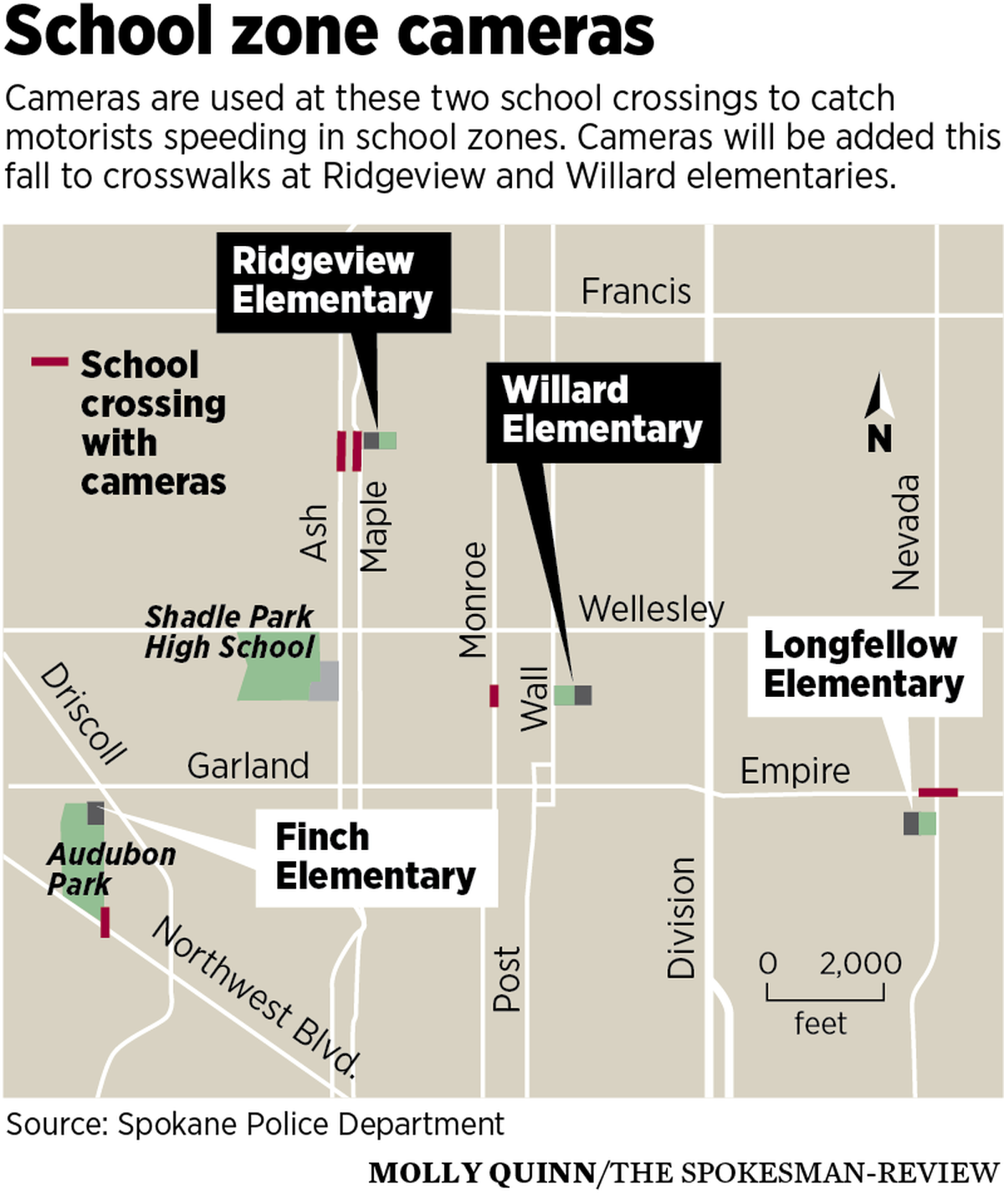

Ticketing speeders in school zones has been a lucrative undertaking. Since 2016, the cameras have caught 21,500 drivers speeding past Longfellow and Finch elementary schools. The fines have generated $4 million. The city plans to expand to camera program to two more schools – Ridgeview and Willard.

The Spokane City Council last week again revised the way it intends to spend those millions of dollars. Through the middle of 2020, the city will set aside $1 million in anticipated collections to pay for more traffic officers to patrol near schools. That’s in addition to the more than $1.2 million in anticipated construction work requested by neighborhood representatives over the next several years intended to slow speeders, including more prominent crosswalks, larger street signs and bigger medians.

City Councilman Breean Beggs sponsored the changes to the program, the latest in a series of revisions that have taken place since cameras were first activated near Finch and Longfellow elementary schools in November 2015.

Spokane City Councilman Mike Fagan, a critic of the camera system, voted against the expansion. Spokane City Council President Ben Stuckart and Councilwoman Lori Kinnear were absent from the meeting.

The new rules allow the Police Department’s Traffic Unit, currently comprised of six officers, to dispatch more officers to school zones than the four neighborhood resource officers who were assigned school traffic duty under a previous resolution by the Spokane City Council. Up to an additional $250,000 can be spent out of the account this fall to compensate officers writing tickets near school zones. The money collected from those tickets will now be used to pay the salaries of the existing four neighborhood resource officers when current funding levels expire at the end of this year.

“The police department has more flexibility,” Beggs said.

The change was a compromise between competing interests on the Spokane City Council: the need for more enforcement officers, and the desire to keep funds in place for the construction projects that are intended to permanently slow down traffic to 20 mph in the designated zones.

“The long-term fix is to change the environment, and to make it safer for children to walk to school,” said City Councilwoman Candace Mumm, who worked with Beggs and City Councilwoman Kate Burke on the new rules.

The city is scheduled to spend more than $250,000 this year on construction projects near schools from the school-zone speeding fund, and applications for future projects have been increasing.

The 2020 cutoff is intended to give the city’s next mayor the ability to guide future spending, Beggs said. Combining school speeding infractions with the city’s cameras enforcing red lights at 10 intersections throughout town, Spokane had about $5 million in revenues at the beginning of June to put toward construction, salaries for traffic officers and other uses, including the city’s walking school bus program, a municipal court judge to process tickets, and other initiatives intended to make walking to school safer.

City officials say the program is meeting its goal – reducing the number of speeders in school zones. Spokane Police Officer Craig Bulkley provided a report to city lawmakers earlier this month that showed the number of tickets issued dropped 20 percent at Longfellow Elementary in 2017, compared to the school year prior. At Finch Elementary, where the number of citations is much lower, tickets dropped 5 percent in the same time period.

Early 2018 numbers show citations will continue to fall this year. The addition of live traffic officers will continue to tamp down the speeding, Bulkley told lawmakers.

“I’m hoping we can have the officers, that sit out there and work those school zones,” Bulkley told the City Council earlier this month. “That has a profound effect.”

Traffic officers review all of the citations issued by the cameras and have the ability to reject citations if it’s discovered the camera was tripped when no violation occurred. Bulkley provided a report that showed during the first five months of 2018, officers tossed 426 violations at red light cameras in town. Examples of when a violation is overruled include when a motorist stops at the intersection, but is beyond the solid line, or if the license plate isn’t visible in the photo, Bulkley said.

Unlike the red-light cameras, those in school zones have been shut off for the summer months, Bulkley said, and state law prohibits the installation of other cameras near areas that see a lot of foot traffic from children when the weather heats up. State law limits automated cameras in Spokane to school zones, red light intersections and railroad crossings. The city could not, under current law, place automated cameras near parks, though there has been a push for greater speed enforcement near city playgrounds.

Officials relied on a speeding study conducted by American Traffic Solutions, the Arizona-based company the city contracts with to maintain and operate the city’s cameras, in June 2017 to justify installing the two new cameras at local schools. That study found that between roughly 60 and 90 percent of drivers passing through the speed zones near the two elementary schools were traveling faster than 26 mph.

In addition to changing the way the camera money is spent, the city renewed its contract with the company through 2023 at an estimated cost just shy of $1 million a year.

While Spokane traffic officials continue work on expanding the school zone camera program, a challenge of an existing camera near Longfellow Elementary is working its way through the legal system. A fined motorist filed a lawsuit in April alleging that the camera on Nevada Street is beyond the 300-foot area near a crosswalk where state law permits cameras to operate.

The city quickly moved to dismiss the lawsuit, arguing it had provided a statement from Bob Turner, a city traffic engineer, that the camera’s location “was the most appropriate site in the vicinity for the school zone in terms of feasibility and safety.”

Larry Kuznetz, the attorney representing the motorist in what was filed as a potential class action lawsuit, argues that’s not enough to meet the state’s rules regarding the 300-foot zone. The camera on Nevada is 385 feet away from a crosswalk.

“We’re arguing the camera is not in a valid school zone,” Kuznetz said. “It’s a little bit different than a lot of the other cases challenging cameras.”

A hearing in the case is scheduled for July. It’s unclear how many of the roughly 16,000 citations issued near Longfellow since 2016 could be invalidated if the court rules in the motorists’ favor. That decision would have to be made by a judge if the case is allowed to move forward, Kuznetz said.

Beggs said he believed the city was on firm footing in the case and shouldn’t affect the automated system’s expansion this summer.

“There have been several lawsuits filed,” Beggs said, noting many of them had been dismissed in favor of the city. “I don’t think we’re particularly concerned about it. If, at the end of the day, the court says we have to move it closer to the school, we’ll go ahead and do it.”