Jim Camden: Would your ancestors be legal immigrants by today’s standards? Not all of mine would

In light of the current debate over immigration, it seems appropriate to confess that my grandfather came to the United States illegally more than a century ago under conditions that today would get him jailed as an unaccompanied minor and booted out if caught.

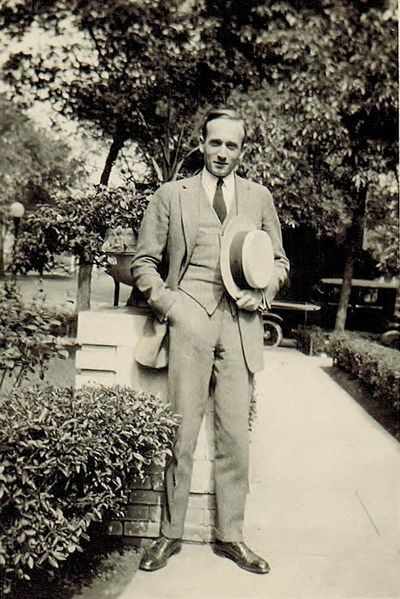

He wasn’t caught then, and maybe wouldn’t be now. Robert Camden came across the northern border, which is not as closely watched or heavily patrolled as its southern counterpart. Born in Montreal in 1897, his parents died within a short time of each other in the first decade of the 1900s. His father had emigrated from England and his mother from France, and neither had any relatives in that country. He had an uncle, aunt and cousins somewhere in Minnesota, so as a young teen with no money he set out to live with them.

Family legend says he swam across the river separating Detroit and Windsor, Ontario, but it’s possible he did something less adventurous but more sensible, like walking across one of the bridges that join the two cities at a time when no one paid much attention to daily comings and goings. He made his way to Minnesota, didn’t last long with relatives and struck out on his own.

He ended up in Chicago, found work as an office clerk in 1913, got a room in the YMCA, and made a lifelong friend in a transplanted Swede named Charles Nordin. When America entered World War I, they joined the Navy together, served on ships in the North Atlantic, and when they got home Charles introduced Robert to his younger sister Viola; they fell in love, got married and had my father.

My grandfather made good money selling municipal bonds in the ’20s, apparently lost quite a bit of it in the crash of 1929 and subsequent Depression, backed Franklin Roosevelt for president, and in 1933 went to Washington to work on the New Deal. He spent about a year there, but became fed up with the federal government and its bureaucracy. He returned to Chicago, became a Republican and went back to selling bonds. When World War II came, my father followed his footsteps into the Navy, serving three years on escort carriers.

My father liked to tell the story of how, when he returned home from the Pacific, they were talking one day about an upcoming election and he asked when my grandfather became an American citizen. I became a citizen when I served in the Navy, my grandfather replied. Doesn’t work that way, my father said, you have to apply.

No you don’t. I’ve been voting in every election for more than 20 years, my grandfather said. Doesn’t matter, my father said, you’re not supposed to. You have to apply for citizenship.

Your mother was born in America, my grandfather said. She’s a citizen so I’m a citizen because we’re married. No, my father said, you’re not.

Having spent his entire adult life considering himself an American, my grandfather apparently wasn’t easy to convince. But he checked and found out my father was right. He somewhat grudgingly went to a federal building in Chicago, filled out some papers, possibly paid a fee, and eventually was granted citizenship. My father couldn’t remember if it took a year or two, but it wasn’t too long. There were no repercussions for living and working in the country without the proper paperwork for four decades or up to a quarter century of illegal voting. (This was, after all, Chicago.)

Whenever supporters of the current no-tolerance policy claim their ancestors immigrated to this country legally and people in 2018 should be held to the same standards, I think about this story, and a few others from my family’s past. One great-great-grandfather supposedly escaped the potato famine by stowing away on a ship from Ireland, getting off in New York, traveling west until he stopped seeing “No Irish Need Apply” signs and finding work on a farm. Pretty sure the farmer didn’t have to check his work visa, or any other kind of paperwork, before giving him a job.

The point is, the standards aren’t the same now as they were for much of the nation’s history. People of English or other Northern European ancestry may have had a difficult time getting to the United States, but once arriving had a relatively easy time setting up shop and blending in. For Southern and Central Europeans, it was more difficult but many were able to get on a ship, go through Ellis Island or some other port of entry, and get into the country. Except for Chinese immigrants, who for years were legally barred from immigrating, nothing faced by would-be Americans of two, three or 10 generations ago compares to what immigrants from Central America, Africa and Asia face now.

We can debate the need for the changes, but it’s dishonest to suggest today’s immigrants aren’t being treated differently and held to much tougher standards than the ancestors of many of today’s natural-born Americans.