Getting There: High speed rail could link Spokane to Cascadia megaregion, but don’t cheer yet

Full-scale mock-up of a high-speed train, displayed at the Capitol in Sacramento. (Rich Pedroncelli / Assoiated Press File Photo)

Much like the Cascadia earthquake, the Cascadia megaregion is coming and there’s nothing you can do to stop it.

One of 11 so-called megaregions in North America, the Cascadia-area population is anticipated to grow by 40 percent over the next 30 years, adding about 3 million people. Its high-tech economy, which heavily contributes to the area’s annual $600 billion economic output, will continue to boom.

The future is bright, and a 250 mph high-speed rail connection between the area’s principal cities will only make it brighter.

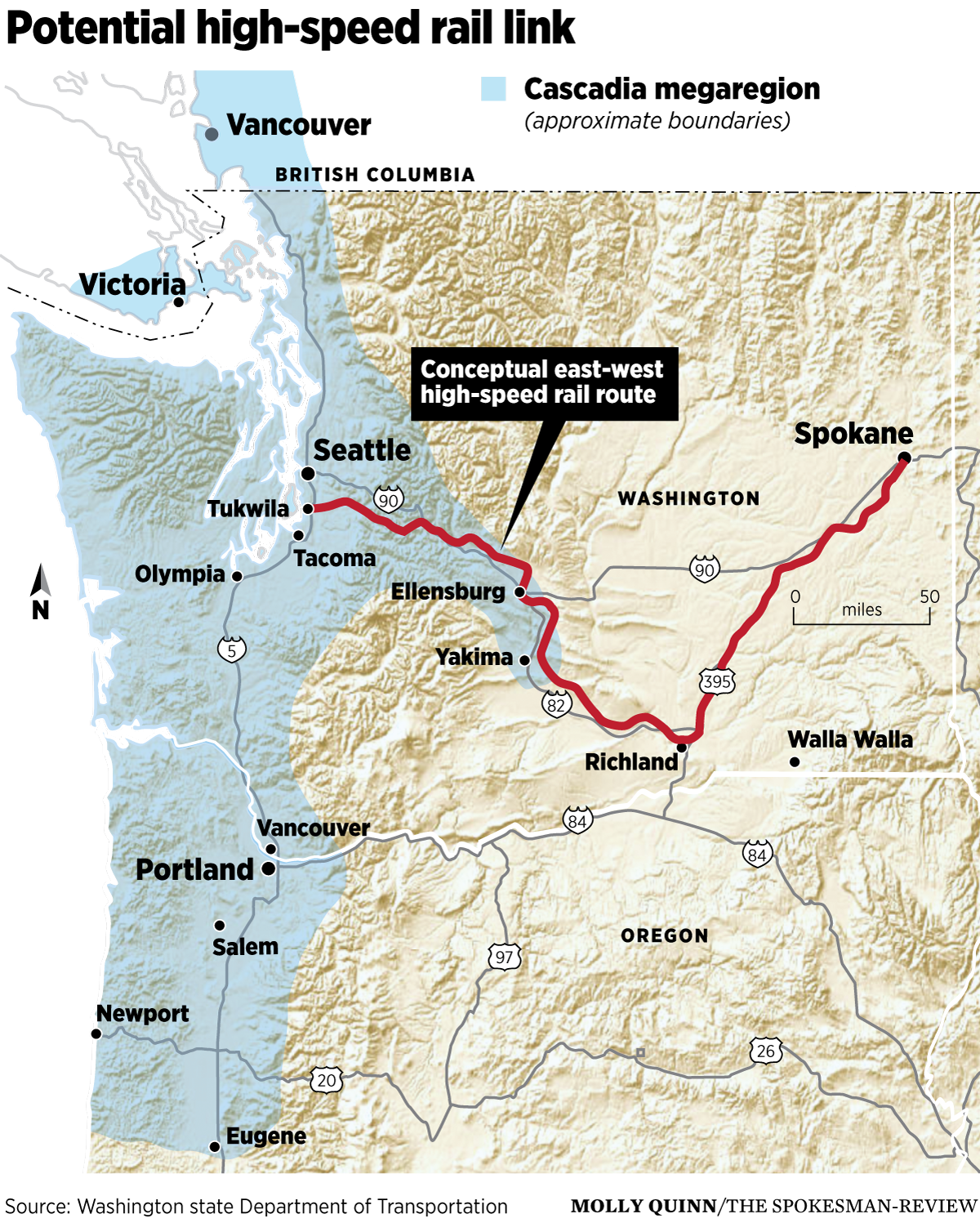

Problem is, Spokane isn’t part of the megaregion, which links Vancouver, B.C., to Portland. Yakima, the Tri-Cities and Eugene are generally considered in its orbit, but Spokane is an outlier.

The good news is that a recent study by the Washington State Department of Transportation examining the potential for ultra-high-speed rail spanning the 466 miles between Vancouver, B.C., and Portland includes a section about connecting Spokane to the Puget Sound area.

Before you throw your hands in the air and mutter something about high-speed rail being unrealistic, consider these examples from China, Japan and France.

The French Train à Grande Vitesse has been tested going 350 mph and has been running since 1981. Japanese Shinkansen is a network of so-called bullet trains in operation since 1964 that can reach a maximum speed of 200 mph. The Shanghai Maglev Train, opened in 2004, is the world’s fastest commercial train, topping out at 270 mph.

These lines have proven their potential, and still more are in the works in China, India and Europe. But another type of high-speed, fixed-route ground transportation is designed to go much faster: the hyperloop. The pneumatic, magnetic and still-untried technology can theoretically reach 760 mph, though it’s only been tested going 240 mph.

WSDOT’s feasibility study primarily focused on the state’s West Side, examining five conceptual north-south routes. And though not one member of the study’s advisory board was from Eastern Washington, the study did throw us a bone.

The one east-west, Spokane-to-Seattle-area route examined in the study would connect to a primary Cascadia line at Tukwila and travel on a portion of a BNSF mainline track. After heading through the 1.8-mile tunnel at Stampede Pass, which is just south of Interstate 90’s route over Snoqualmie, the rail would run through Ellensburg and Yakima Valley to the Tri-Cities, where it would connect with the Pasco East mainline and turn north to Spokane through the scablands.

The four station locations along the corridor would be Spokane, the Tri-Cities, Ellensburg and Tukwila.

The route is 310 miles, so at the top theoretical speed the journey could take an hour and 15 minutes. But they won’t go that fast, according to Janet Matkin, a spokeswoman with WSDOT.

“The Stampede Pass rail line would need to be upgraded to accommodate high-speed travel,” Matkin wrote in an email. “In this feasibility study, it was assumed that the passenger trains would travel at less than 90 mph and would share the right of way and tracks with freight trains.”

That’s bad news on top of an unlikely event. In the long chance the route does come east, and on the rare occasion the busy freight corridor allows passenger trains to pass through unimpeded, we’re looking at 3 1/2 hours from Spokane to Tukwila.

It gets worse. Matkin wrote that right-of-way property may be needed to make the east-west route viable, which isn’t even a given. Clearly, more analysis will be needed to determine the viability of this connecting route.

So the technology and route are there, but the viability is iffy. The price, however, is something else completely.

The feasibility study itself cost $300,000. Gov. Jay Inslee has requested $3.6 million in his supplemental budget to continue studying ultra-high-speed rail, including a “business case analysis” that would give more substantive information on the policy and financial needs to build such a route. Spokane isn’t mentioned in that request at all.

The cost to build the mainline itself, between Vancouver and Portland, is estimated at somewhere between $24 billion and $48 billion, according to the study. That’s equivalent to 12 to 24 times the amount of money the Legislature just allocated in its capital construction budget.

The report doesn’t mention potential cost for the Spokane route, other than to note that while it “could add a 15 to 25 percent increase in network impact ridership, it requires initial subsidies to be viable.”

So pony up, Legislature. But will they? The report was released four days before the Amtrak derailment near DuPont, Washington, which killed three people. How people view that incident may impact the future of ultra-high-speed rail. Will they condemn fast trains altogether? Or will they realize that the misnamed high-speed Amtrak route was running on lines not originally designed for such a use?

It should be noted that high-speed rail is one of the safest modes of travel. Not one passenger has been killed or injured on Japan’s 60-year-old system. Not one fatality has occurred on France’s nearly 40-year-old system.

Regardless, Spokane’s future – at least when it comes to high-speed rail – is dim.