New frontier for craft U.S. whiskey may be underfoot in Olympic Peninsula bog

Matt Hofmann, the master distiller at Westland Distillery in Seattle, holds a piece of peat during a visit to a peat bog on Washington state’s Olympic Peninsula near Shelton, Wash. (Associated Press)

SEATTLE – Matt Hofmann walks along a small brown pond, the earth of its bank springing underfoot like a muddy mattress.

The ground is, in fact, floating. It’s a peat bog on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, and it’s from here that Hofmann, the co-founder of Seattle’s Westland Distillery, is taking an unusual step for America’s booming spirits industry: making a whiskey whose “terroir” literally involves local dirt.

For centuries, distillers in parts of Scotland have made whiskey using smoke from smoldering peat, a coal precursor made of slowly decayed plants. That gives their drams the campfire flavor for which they’re known.

In America, not so much. Bourbon traditionally hasn’t been made with smoked grains. Nor have American distillers focused on Scotch-style single-malt whiskeys, those made at a single distillery using only malted barley, rather than corn, rye or wheat.

For Hofmann, peat has become one key to making a Pacific Northwest whiskey, along with lesser-known strains of barley that thrive here and barrels made with a regional species of oak.

“Every whiskey anywhere around the world can trace its lineage back to peated whiskey, which to us makes it an incredibly important style,” Hofmann said. “We can take our whiskey, follow this same model that has existed … and say, ‘This is the difference you can trace back to the Pacific Northwest.’ What’s cool about it is it’s just as authentic as Scottish whisky.”

More U.S. spirit makers have branched into single-malts featuring local ingredients – some in the Southwest now use mesquite smoke – but hardly any have gone so far as experimenting with peat. Peat’s often found in protected wetlands, and a lack of traditional knowledge about it has posed a formidable hurdle.

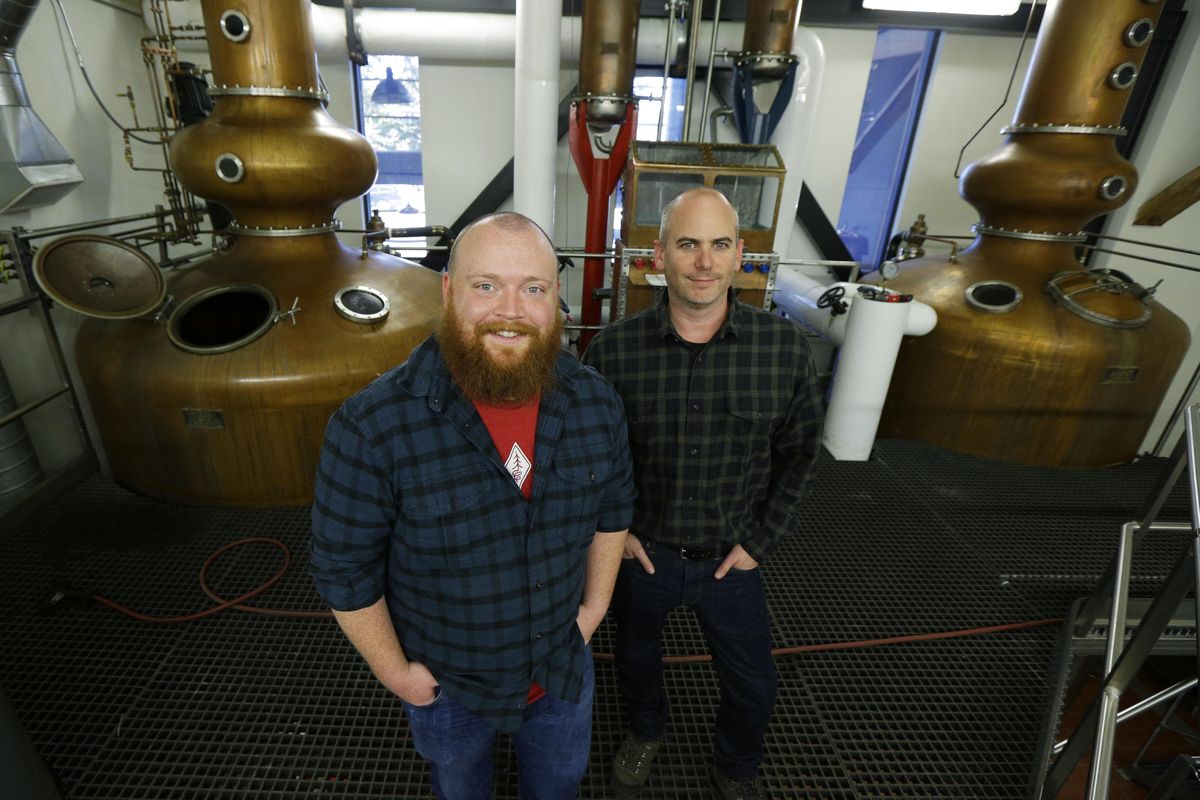

Hofmann, a 28-year-old with a ruddy beard, grew up in Tacoma and became fascinated with distilling as a teen. His first still was a converted water purifier, which he used to make apple brandy in his freshman dorm room at the University of Washington. His goal was to hone his liquor-making chops, but it didn’t hurt his popularity either, he said.

He dropped out to study distilling in England and Scotland, and he began to think about what subtleties of flavor Northwest peat might impart. After all, aren’t the bog plants here different, including the fragrant, citrusy rhododendron relative known as Labrador tea?

He and a high-school classmate with a family lumber fortune, Emerson Lamb, started Westland in 2010 intent on finding out. Lamb has since left the company, which was recently acquired by the French spirits behemoth Remy Cointreau.

Hofmann’s peat search brought him to Doug Wright, a retired sheriff’s detective who operates a bog northwest of Olympia. One of peat’s more interesting properties is that it acts like a sponge, and Wright mostly sells it to agencies for soaking up oil or chemical spills. He also sells it as garden soil, including to some of the state’s legal marijuana growers.

Peat forms over millennia as mosses, sedges and other plants decay in acidic water. A lack of oxygen slows the decomposition; ancient bodies have been found well-preserved in European bogs.

Wright’s bog goes down 40 feet. He’s found preserved beaver dams at 15 feet, and at 18 feet is a layer of volcanic ash, presumably from the eruption of Mount Mazama in Oregon – now Crater Lake – more than 7,000 years ago.

When the peat is dug, it’s about 90 percent water. Wright piles it and lets it drain before running it through a giant screw-press, which squeezes it out further. At this rate, he said, it would take 300 years to exhaust the bog.

Even with a source for peat, there was the question of what to do with it.

“Nobody in the U.S. knew how to make peated malt,” Hofmann said.

Single-malt whiskey is made with malted barley – barley that has germinated, sprouting tiny roots. The germination develops enzymes that convert starch into sugar, which becomes alcohol.

To get the barley to germinate, distillers soak it in water. After a few days, they halt the growth by drying it out.

In Scotland, that’s often meant using heat from smoldering bricks of peat, a readily available resource there. Workers spread thousands of pounds of malted barley across a perforated floor. The heat and smoke from a kiln below rise and dry the grain.

But such traditional methods can yield inconsistent results. Hofmann said he wanted to use peat “in a way that made sense in the 21st century.”

He connected with a new company north of Seattle, Skagit Valley Malting, which supplies barley to Northwest breweries. It devised a way to smolder peat pellets in a smoker hooked up to the giant, digitally controlled, rotating drums it uses to malt the grain – a sophisticated update to floor maltings.

Distillers in Japan, Sweden, Denmark, Tasmania and elsewhere have also faced production challenges in using local peat, but now do so successfully, Scottish whiskey writer Dave Broom said.

“There is a definite terroir aspect to peat,” he wrote in an email. “The fact that you can identify different components within different regions of a tiny country like Scotland makes this a fascinating area for distillers who are keen to establish a sense of place in their whiskies.”

One of those distillers is Emily Vikre of Vikre Distillery in Duluth, Minnesota.

“We have access to local peat, and we’ve worked with farmers who have peat in their fields,” she said. “The hang-up is trying to malt our own grain. So far, we’re not very good at it. But we’ve made things that really smell bad.”

Westland has also made whiskey with peated malt from Scotland. But last year, the company barreled its first local peat whiskey – 70 casks, enough for 15,750 bottles. This year, they filled 80. It’s a small sliver of the 4,000 barrels Westland has aging in rack-houses on the Washington coast.

It still needs to age; Westland won’t even consider bottling it until 2020. Meanwhile, the industry’s waiting. Fred Minnick, a Kentucky-based whiskey writer who has visited the bog, calls Westland an “an extremely important craft distiller.”

“When they get their American single-malt peat train going, I think they just opened an entirely new door for American whiskey,” Minnick said.