Landmarks: From Spokane, he flew into history: North Central graduate served with Tuskegee Airmen

This is the house in Spokane’s West Central Neighborhood where Jack D. Holsclaw was raised. (Stefanie Pettit / The Spokesman-Review)

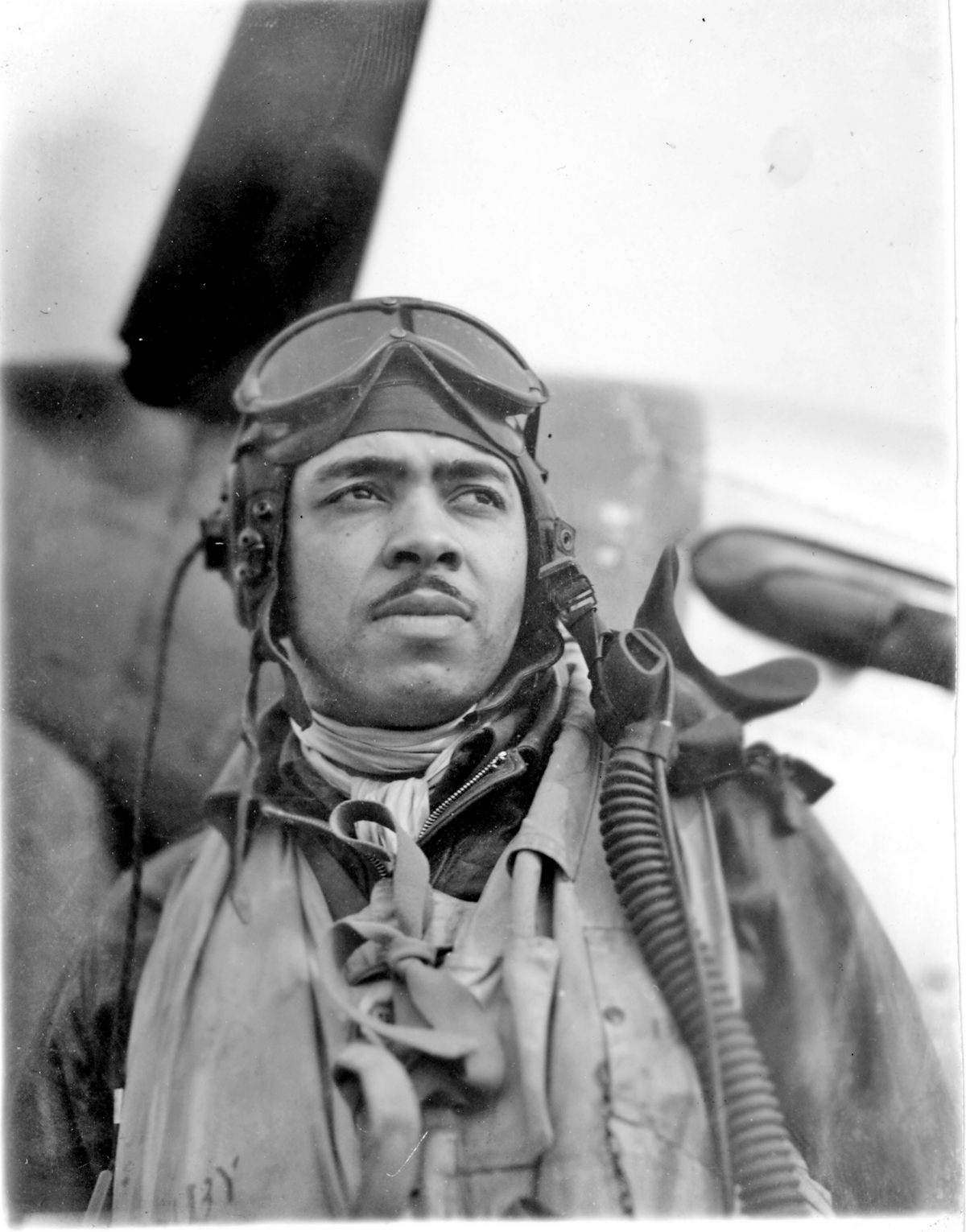

In World War II the 100th Fighter Squadron in the U.S. Army Air Corps’ 332nd Fighter Group flew 15,000 sorties in Europe and North Africa. In so doing, they flew into the history books for their bravery, skill and amazing record of accomplishments. They were the famed Tuskegee Airmen, America’s first African American military pilots.

Lt. Col. Jack D. Holsclaw, of Spokane, was one of them.

Jack Holsclaw was born in Spokane in 1918 to Charles Holsclaw, who worked at The Crescent department store, and Nell Holsclaw, a teacher, and grew up in the city’s West Central Neighborhood, where the academically gifted young man earned good grades at North Central High School and played baseball and basketball. At age 15 he became the first black student to earn an Eagle Scout badge in Spokane.

The family home, a four-bedroom Craftsman style residence built in 1905 at 2301 W. College Ave., sat in a residential neighborhood among a collection of residences that reflected a variety of architectural styles – including Queen Anne, Victorian, bungalows and cottages. After graduating from high school in 1935, he attended Whitworth College for a year, and while there dated a young woman named Bernice Williams, who would later become his wife.

Because he loved baseball he transferred to Washington State College in Pullman so he could play under famed coach Arthur “Buck” Bailey. Because of his good throwing arm, he was a centerfielder, and contributed to the Cougars becoming co-champions of the Pacific Coast Conference’s Northern Division.

In his senior year he moved on to Western State College in Portland so he could study chiropractic medicine, and while there he also entered the government-sponsored Civilian Pilot Training Program at Multnomah College and earned a pilot’s license.

Although he was already a board-certified chiropractor, in 1942 he enlisted as a private in the Army to join the war effort. He was able to enter flight school and trained at the Tuskegee Army Airfield at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, which had been founded by Booker T. Washington, America’s preeminent African American leader in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The nearly 1,000 African American pilots who trained there would become known as the legendary Tuskegee Airmen, the “Red Tails,” because the tails of their fighter planes were painted that color.

During their WWII assignment to escort Allied bombers and fend off Nazi fighters, 66 of them were killed in action, 32 became prisoners of war after being shot down and 96 of the Red Tail airmen were awarded individual Distinguished Flying Crosses. And of the thousands of bombers they escorted and protected, they lost only 27 U.S. bombers to German planes.

Adding to their lasting legacy, most all historical accounts of the Tuskegee Airmen credit them with jump-starting the move to integrate America’s armed forces.

After earning his wings and a commission, Holsclaw married Bernice, and in 1943 was shipped to Italy. At first he piloted a Bell P-39 fighter and flew missions protecting ships and coastal patrols. The 332nd Fighter Group moved to Republic P-47 Thunderbolts and finally the powerful North American P-51 Mustangs. Holsclaw named his P-51 “Bernice Baby” in honor of his wife, and flew with his squadron escorting and shielding American bombers.

During the war Holsclaw flew in seven major campaigns, including 68 combat missions (flying 18 of them in a 20-day period). In his book “WSU Military Veterans: Heroes and Legends” author C. James Quann tells of his February 1998 interview with Holsclaw in which the famed pilot recalled his most harrowing battle.

On July 18, 1944, 64 P-51 Mustangs had taken off for an escort mission over Munich, but engine trouble forced their leader to return to the airfield. Time was short for them to meet their assigned group of bombers, so Holsclaw assumed command and led them into battle in adverse weather conditions. Three of the squadrons formed an umbrella over the bombers and one squadron, under Holsclaw’s leadership, engaged the enemy.

A German force of 300 fighters attacked, but Holsclaw’s squadron held them off. Eleven German planes were shot down, and he was credited with taking down two Messerschmitt 109s. The heavy American bombers got through and hit their targets. For his actions in this battle, Holsclaw was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, one of the 24 medals and citations he would receive during his military service.

After the war, he returned to the United States and continued his career in the military, which included flying support missions between Japan and Vietnam in the early days of the Vietnam War, pilot training and a long list of distinguished accomplishments. He retired as a lieutenant colonel in 1965.

Jack and Bernice Holsclaw always wanted to return to Washington, so in 1973 they moved to Bellevue, where he worked in banking. They took up residence in Arizona when he retired permanently in 1983. He died in 1998; Bernice died in 2006.

David Bray, a retired Realtor, and his wife Charlotte, a retired child care worker, now own the house in the West Central Neighborhood where Jack Holsclaw lived his young years. Bray remembers that when he was an air traffic controller in the U.S. Marines in the 1960s and ’70s, “we used to talk about what phenomenal pilots those Tuskegee Airmen were, everything they accomplished and everything they had to face in those days.”

“I really appreciate those heroic men, and now I’m living in the house that one of them grew up in. That’s a wonderful thing to discover.”

____