2017 saw highest number of officer-involved shootings in more than two decades

By most accounts, Antonio Davis is lucky to be alive.

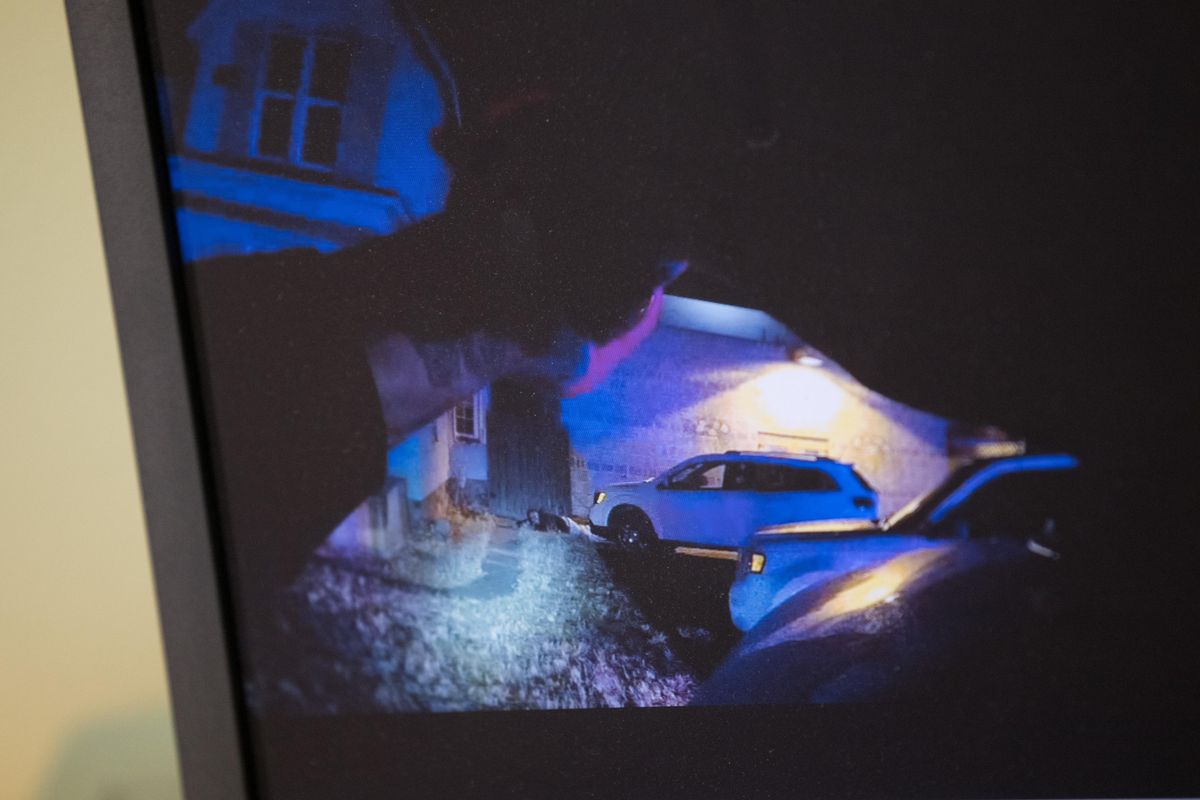

After leading police on a short, high-speed chase through a north Spokane neighborhood late last year, the 25-year-old crashed his car into a tree. As it came to a thud, both front doors sprung open, and Davis and his passenger ran in opposite directions.

The two officers chasing them in a cruiser stopped, hopped out and gave chase, according to body camera footage. Davis was a murder suspect out of Reno, Nevada, so the officers had their guns drawn as they tracked Davis to a driveway of what appeared to be an empty house.

It was a perfect alcove, trapping the young man as he tried but failed to jump over a fence.

“I will shoot you,” Officer Chris McMurtrey yelled, his pistol pointed at Davis. Information at the time also warned police that Davis was known to carry firearms.

When Davis turned in another attempt to escape, he ran east – straight toward McMurtrey’s partner, Officer Tucker Seitz, who was flanking Davis from behind a vehicle. The officer discharged two rounds, one of which hit Davis in the right bicep, dropping him instantly.

“Ahh, ahh,” he screamed. “You shot me. You shot me.”

The moment the bullet struck Davis, he became a statistic during a year with abnormally high officer-involved shootings. By year’s end, he would be one of eight people shot by law enforcement officers in Spokane County in 2017, and one of seven shot by Spokane police officers – the most for the department since at least 1995, according to department data.

He was also one of two suspects to survive being shot by police, something that isn’t lost on his mother.

“I think he was lucky,” said Vannessa Smith, who said she was barred from her seeing her son while he lay on the ground. “I thought my son was dead. I thought he was dead.”

Since 2008, Spokane has averaged about three officer-involved shootings a year, with about two out of those three dying. Last year, those statistics worsened as five of the eight were shot dead.

The numbers, while not ready to be called a trend by city leaders, have startled some.

“I’m concerned that people are dying,” said Bart Logue, Spokane’s police ombudsman. “Any time we end someone’s life in an official capacity, it should really give you pause to see if there’s any other action taken that could mitigate that.”

Spokane police Chief Craig Meidl, who took over for the department in 2016, has stressed his desire to curtail deadly force encounters with officers through updated training points that stress less-lethal options before guns are considered.

Given the department’s new direction, Meidl saw this year’s spike as an outlier.

“My anticipation is that this is a not a norm,” he said. “My hope is that having an updated policy will not only keep officers more safe but the community as well.”

Late last year, he and Logue met to discuss strategies on how best to update the department’s policies. Those discussions are ongoing, and both hope to have substantial proposals to bring to the Spokane City Council later this year.

“Reducing police shootings is going to be something I’m going to be very passionate about in 2018,” Logue said.

In late January, Maj. Kevin King was one of several speakers at a NATIVE Project meeting at the West Central Community Center. Facing a crowd, he shared a statistic: Three of the seven people shot by police last year were Native Americans. The NATIVE Project is a nonprofit that promotes healthy lifestyles.

“Obviously, we look at those and there’s a story behind each of those numbers,” he said.

Police say understanding why the shootings happen is complicated.

For example, in 2008, when Spokane had 1,352 violent crimes – the second highest total in the past 10 years – police didn’t shoot anybody. In 2014, when the number of violent crimes fell by about 200, according to the FBI’s Uniformed Crime Reporting statistics, four people were shot by officers.

“It’s concerning because at times we do feel like we’re making huge efforts to prevent these types of things,” King said. “We’re constantly doing the Monday morning quarterbacking to see what we can do to improve the situations.”

In every fatal shooting this year, the victim was found to be carrying a deadly weapon, or was in the process of using it when police were called. In four of the incidents, the person had a gun.

King and Meidl said officers have noticed an increase in the number of firearms they’re confiscating when arresting suspects, though it’s not something they track.

What’s especially concerning, they say, is how easily repeat offenders are gaining access to weapons once they’re released back on the streets.

“Officers are seeing the number of guns on the street at unprecedented levels,” Meidl said. “I would also argue that we are seeing a lot more dangerous criminals who are out on the street.”

Under federal and Washington law, it’s illegal for felons to own guns under most circumstances.

King said when officers respond to calls, the circumstances of the crime being committed dictate the level of response they’ll employ, firearms included.

In Davis’ case, officers believed they were looking for a murder suspect based on a bulletin from Reno. Smith said Davis’ attorney told the two there is still a murder warrant for him from Nevada.

When he was arrested, Davis didn’t have a gun on him, though one was found in the car. And his passenger is believed to have ditched a gun while running from police.

“They’re looking at a lot of different factors,” King said. “They’re looking at the crime involved, the threats. Having a gun is just one of those things.”

Context works both ways. In December, officers were called to a downtown apartment building where a man was reportedly breaking windows, brandishing a knife and asking for police to shoot him in what’s called “suicide by cop.”

When a group of officers confronted him in a hallway, he exited his room naked, a knife held high above his head. He started walking toward the officers when he was shot with a less-lethal 40 mm blue foam launcher and a Taser. The Taser barbs didn’t connect, but the blue foam did: It hit him square in the pelvis, taking him to the ground.

According to an interview with Officer Kyle Yrigollen conducted by city officials after the incident, the man was seconds away from being shot by bullets. Had it been a gun instead of a knife, chances are higher police wouldn’t have used less-lethal options.

In that case, officers believed the man was suffering from mental health issues. Meidl said recently that, among other options, he’d like to see increased state funding for mental help.

“The number of confrontations between law enforcement and people in mental crisis is staggering,” he said. “There are not enough resources for these people to get long-term help for their betterment.”