Research sheds new light on EWU professor’s Antarctic dino-discovery

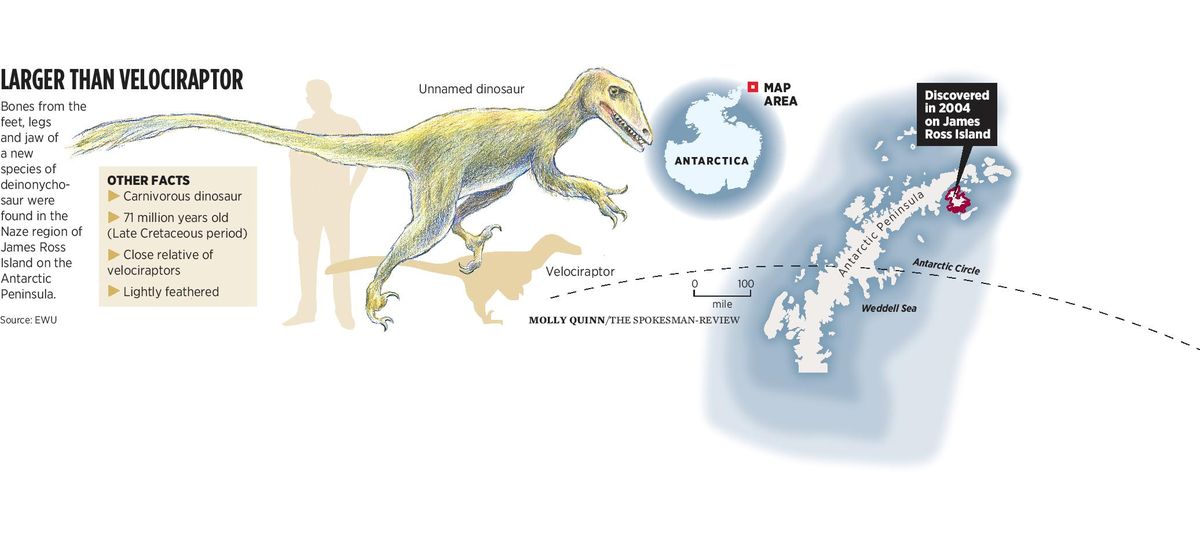

Eastern Washington University professor Judd Case, who discovered a new species of dinosaur in Antarctica in 2004, poses for a photo in his office on Wednesday, Feb. 7, 2018, in Cheney, Wash. The skull in front of Case is a model of a velociraptor. Case said the dinosaur he discovered is larger. (Tyler Tjomsland / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

You can tell a lot about a dinosaur by its ankles.

For instance, ankles told Eastern Washington University paleontologist Judd Case that the dinosaur he discovered in Antarctica in 2004 is more primitive than its relatives, such as the velociraptors made famous by “Jurassic Park.”

Case and his former student, Ricardo Ely, have submitted a paper for publication outlining the discovery and explaining for the first time how it fits in with other known species of dinosaurs.

The discovery was far from a full skeleton: just part of a left foot and leg. But there’s a lot paleontologists can learn from a few bones.

Case’s find is a deinonychosaur, the group of dinosaurs most closely related to birds without being birds themselves. Based on where it was found, it’s thought to be about 71 million years old, putting its time frame toward the end of the Late Cretaceous period.

That period ended about 65 million years ago, when dinosaurs became extinct.

The bones of many other dinosaurs from around the same period have been found in the same area of James Ross Island.

“This area has been really rich in giving us a view of life at the end of the Cretaceous before the dinosaurs check out,” Case said.

He’s written about the discovery and the geology behind it, using the presence of other species in the same layers of dirt to date the finding. But until he began working with Ely in 2014, no one had tried to explain how this group of bones fits in to what we know about similar dinosaurs.

“Nobody had ever put together all these different dinosaurs,” Case said.

Dinosaur taxonomy – the branch of science that classifies organisms – is inherently controversial. Different scientists have their own theories about relationships based on their own discoveries, and a bit of guesswork is often involved.

“Any of these trees about the relationships of dinosaurs are always going to change as more data is added,” Case said.

Ely got involved when he was studying biology and geology at EWU. A Spokane native, he was interested in paleontology and started working with Case in summer 2014.

Before Case’s dinosaur, paleontologists typically split deinonychosauria into two families: dromaeosaurids and troodontids. Both are two-legged dinosaurs with a distinctive curved claw, the velociraptor talon made famous by “Jurassic Park,” as the second digit on the feet.

In dromaeosaurids, the claw is larger and used on prey, resembling the movie version much more closely. One of the upper toe bones, which connects to the lower toe and then to the claw, is also grooved at the end of the bone. That connection limits the motion of the claw farther down the foot, ensuring it can only move vertically. That limited range of motion lets the claw specialize in holding or tearing prey.

Troodontids have the claw, but it’s smaller and missing that groove, suggesting it was less specialized for hunting.

Case initially thought the new species could be a dromaeosaur, but further examination showed its claw was missing the telltale groove in the foot bone.

“When I started looking at it, it was clear that it was a very different type of animal,” Ely said.

It’s also small: much smaller than a velociraptor claw, even though the deinonychosaur stands about twice the size of 3-foot velociraptors.

The creature’s ankle bones are also strange. In velociraptors and other related dinosaurs, the astragalus – one of two ankle bones – has a triangular portion extending up toward the tibia. This served to stabilize the legs, allowing dinosaurs to run upright.

Case’s deinonychosaur instead has a fusion between the calcaneum, the outer ankle bone, and the fibula. It’s a more primitive way of achieving the same impact: a more stabilized leg and ankle.

“It’s a different way of solving a problem,” Case said.

Based on those features and computer modeling of how they compare to known species of dinosaurs, the pair concluded the dinosaur is a type of deinonychosaur, but that it doesn’t belong in either of the two families scientists have yet described.

“If we had a more complete skeleton, we might be able to pick out many other features that look primitive,” Ely said.

That conclusion is the only piece of their analysis Case said might ruffle some feathers, though scientists he’s worked with in Antarctica said it’s the most logical conclusion from what they know.

“Some of the reviewers may not like that relationship,” Case said.

Their paper has been submitted for review to the Journal of Cretaceous Research. If and when it’s published, Case will officially get to name the dinosaur.

Ely is now pursuing a master’s degree in geology at the University of Indiana, where he’s studying traits of other carnivores through both fossils and modern species.

“Most undergrads don’t get to work on describing a new species of dinosaur. It’s been an incredible opportunity for me,” he said.

Case said he loves his work, in part, because it sheds light on how ancestors of modern species of plants and animals arrived on different continents.

When his dinosaur walked the Earth, Antarctica was green year-round and connected to Australia and South America. Because it was the last part of the world to get flowering plants, its animal species often appear more primitive than their contemporaries in other parts of the world, which can help scientists trace when various characteristics spread.

“Antarctica is the last outpost for many of these primitive dinosaurs,” he said.

It’s an area rich for new discoveries, he said.

“Most of these dinosaurs have literally been found in the last 15 years,” Case said. “It’s opened probably the bigger vistas of what’s going on down there.”