Getting There: Riverside Avenue redevelopment could take a lesson from the past

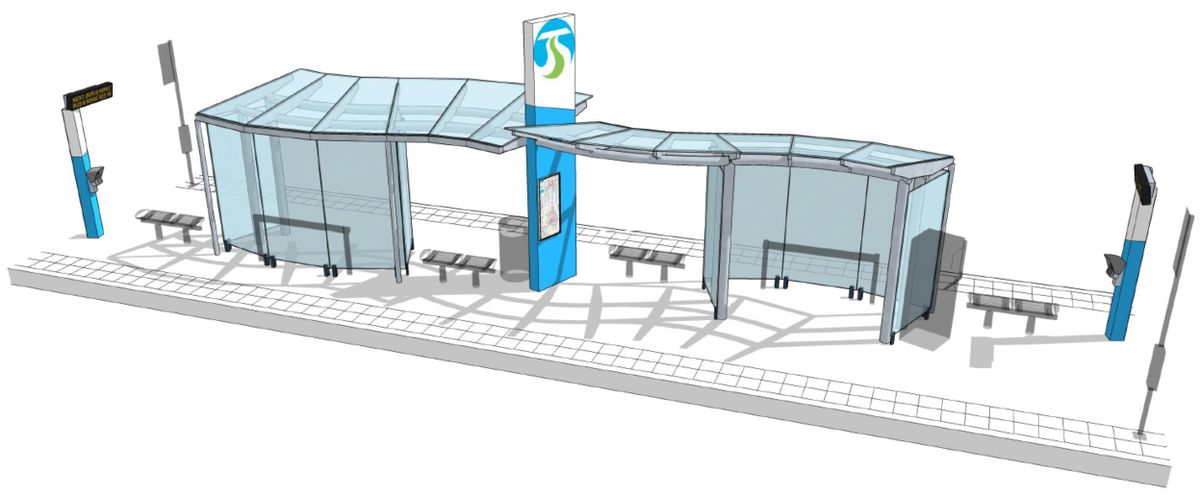

High speed service and convenience will be achieved with elements such as pre-board ticketing, level boarding and improved stations with real-time signage, wayfinding and other amenities. (City of Spokane)

Riverside Avenue might soon be a very modern street.

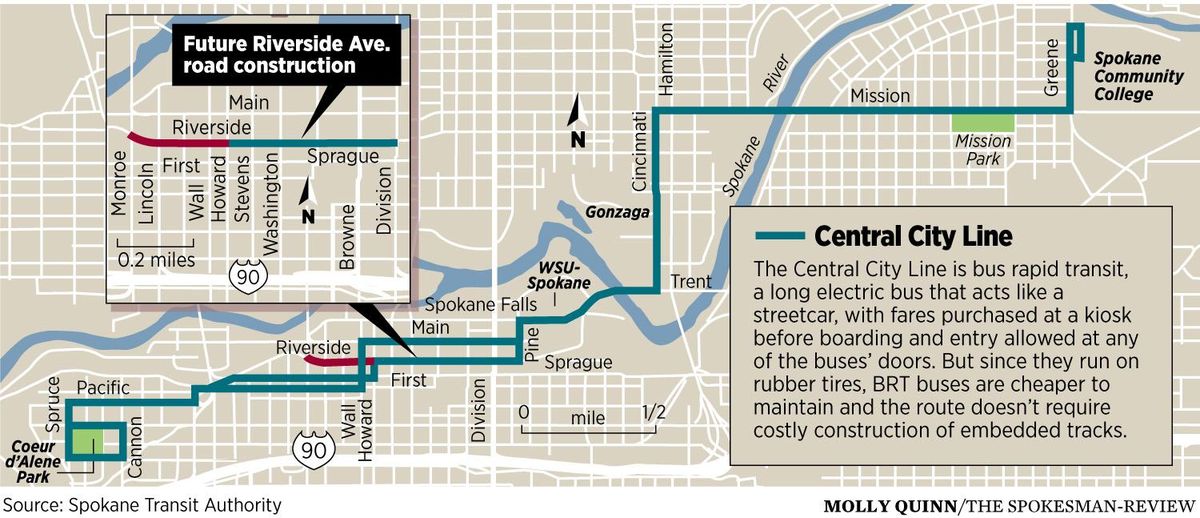

As the once-bustling thoroughfare gets in line for its turn at the roadwork currently reshaping Spokane’s commutes, it will be the first street remade in anticipation of Spokane Transit Authority’s Central City Line.

Makes sense that the center of the city gets the first bit of a central line.

Concepts from the city show raised transit stops in the center of the road, accompanied every now and again with angled parking in the center lane. Bike lanes will run in either direction, and the road – which has been remade for automobiles countless times over more than 100 years – will go from four lanes to two.

The bus rapid transit route connecting Browne’s Addition to Spokane Community College is an electric bus that acts like a streetcar, with fares purchased at a kiosk before boarding and entry allowed at any of the vehicle’s doors. Unlike a streetcar, the buses will run on rubber tires, avoiding the costly construction of embedded tracks.

But some of this isn’t for sure. While the coming of the Central City Line is not up for debate, the future look of the 6-mile route remains an open question. The city is seeking feedback on concepts for Riverside. Construction isn’t expected until 2019, and the roadwork is anticipated to be done in phases over three construction seasons.

The city has six concepts for Riverside, and the one described above is what Riverside could be at its best. It should be this way.

Riverside was once the busiest road in Spokane, with streetcars, horses, bicyclists, pedestrians, carriages and automobiles jostling in a slow-paced and relatively safe chaos. What it looks like now is the result of 20th-century planning, when all decisions were made with the automobile in mind. From road-widening and lane-adding to the demolition of large, historic buildings for parking lots, the quiet Riverside we have now is the result of the car.

With the city in the midst of conceiving how Riverside will look in the future, the automobile remains the most dominant form of transportation by far. As such, one of the city’s concepts – its weakest – largely keeps Riverside how it is, with the snaky-sleek electric bus sharing the wide and barren road.

Know the history of Riverside, and you may be more amenable to the biggest changes the city has proposed.

Before the mud was done away with, and well before the car, tracks were put down and horses pulled Spokane’s first streetcars up and down Riverside. It was April 15, 1888, when a large crowd gathered to watch a streetcar “gaily festooned with the American flag” make its maiden voyage on Riverside. The route connected the city core to Browne’s Addition, linking shop owners to their large homes and bringing maids and house servants to their jobs in the new mansions built by barons.

The streetcar might have signaled the big-city future facing Spokane, but the muddy streets of the frontier town remained a daily annoyance. In 1891 and 1892, Dope Smith, a pioneer tobacconist, ran a “ferry” across Riverside. With a 4-foot-long rope tied to the bow of a small, hand-built boat, Smith charged to pull people across the “lob-lolly of ankle-deep mud.” The police chief didn’t like this vigilante transit system and destroyed the little boats any chance he could.

In 1898, a 2-inch-thick layer of asphalt, Riverside’s first pavement, was put down, but only after the old dirt road was plowed – a task that took seven men and four double teams of beasts of burden, thanks to the many years of travel that had packed down the dirt.

Ten years later, in 1909, the jostling free-for-all between the era’s wide variety of transportation options inspired the city to propose a newfangled idea to put parking spaces in the middle of Riverside. Business owners balked at the plan, and a petition soon had 50 signatures from Riverside proprietors.

In 1936, coming up on a sixth decade of service, streetcars were discontinued on Riverside. The city was repaving the street, and the streetcar was outdated. Only Main and Trent avenues, now Spokane Falls Boulevard, still had streetcars.

Over the coming years, the city widened Riverside numerous times. In 1943, they bumped out to 30 feet wide, and in 1953, they enlarged it again. In 1970, the city said it was going to do away with parking on Riverside to allow for seven lanes of traffic, but never did.

Riverside’s wide lanes did what they were designed to do: encourage driving. For decades, young motorists enjoyed “tooling” in a circle downtown, a ruckus that made older folks’ fingers wag.

A 1980 Spokesman-Review article said Riverside became a “riot scene” after impromptu drag racers hit 60 mph. When police arrived at 3:30 a.m., belligerent crowds chucked beer and wine bottles at them. Forty officers ended up responding, but only three people were arrested.

During the 1980s, Riverside carried about 14,000 vehicles a day. That’s a lot, as much as Second and Third avenues carry today.

But now, average daily traffic counts on Riverside peak at 5,800, lower than Spokane Falls Boulevard’s 9,500. The city projects the road will see 7,000 vehicles a day by 2040. The hum of this storied avenue is gone.

All of this is to say, Riverside has changed a lot during its 140 or so years. Why not give it another change, a big one to drag it into the 21st century, all the while bringing back some of its fixed-transit route and bicycle- and pedestrian-friendly past?

The six concepts the city has for the future of Riverside are just different degrees of change. With the most change, the road has center-lane transit stops, bike lanes, lane reductions, turn lanes and radically different parking configurations. The five remaining concepts feature smaller degrees of modification, losing bike lanes, center-lane stops and the rest of the amenities until the plan looks close to how Riverside appears now.

An interactive presentation of the concepts is available at the city’s website, and it’s included with a survey so the city can hear what people think.

But, quickly, here are the six concepts:

The first has transit stops for the Central City Line and angled parking, both placed in the center of the road, transitioning between each other. Bike lanes run in both directions, and vehicle lanes are reduced to one lane going either way. Curbside parking remains on just the north side of the road, keeping the south lane open for the transit agency’s regular fleet of buses.

The second concept is the same as the first, but instead of bike lanes, bicyclists would remain in the traffic lane with other vehicles. Parking would be maintained on both sides, as well as in sections of the roadway center.

The third idea does not include center-of-the-road parking, but it does keep central boarding. Bike lanes and curbside parking remain on both sides.

The fourth option keeps two lanes for traffic in either direction, has bicyclists using the traffic lanes and puts transit stops and parking in the center but does away with curbside parking.

The fifth puts the transit stops on the sides of the road, adds bike lanes, keeps curbside parking and maintains four lanes of traffic.

The sixth and final option places transit stops curbside, adds bike lanes and keeps parking on both sides of the road but reduces lanes to one in either direction, with a center turn lane.

And before you ask, yes, the broken and degraded pavement that gives Riverside that lovely feeling of being on the moon will be replaced.

Learn more at a public open house on Tuesday, Feb. 13, from 4:30 to 6:30 p.m. in the STA Plaza Rotunda, 701 W. Riverside Ave.

Or review the online presentation and fill out the online survey at the end. The presentation can be viewed at my.spokanecity.org/riverside-avenue/.