Washington nurses, health care workers are dying of opioid overdoses

Tami Cleveland looks at sketches made by her stepmother, Beth Cleveland, at her home in Rosalia Sunday, Mar. 12, 2017. Beth Cleveland, a hospice nurse, died of a painkiller overdose in 2012. The veteran nurse had sought the painkillers for debilitating headaches, but inadvertently overdosed. Jesse Tinsley/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW (Jesse Tinsley / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Tami Cleveland was terrified as she drove to her parents’ house in Veradale on a September evening in 2012.

Her stepmother, Beth, who suffered from debilitating migraines, hadn’t answered her call that morning. Cleveland hurried over after work to check on her, her anxiety growing when no one answered the door.

She let herself in and found Beth upstairs.

“She was sitting in her chair and her head was leaning against the headrest, and her mouth was open, and her eyes were open,” Cleveland said. “I went and shook her. She was cold to the touch.”

In her bathroom, Cleveland found a bottle labeled with a prescription for 300 hydrocodone pills, filled the day before. It was empty.

It’s a story that’s all too common across the United States, where more than 50,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses in 2016.

But Beth was different from most of the deceased. She was a registered nurse. A 53-year-old equipped with knowledge about the dangers of the powerful painkillers she was taking. And she was far from alone.

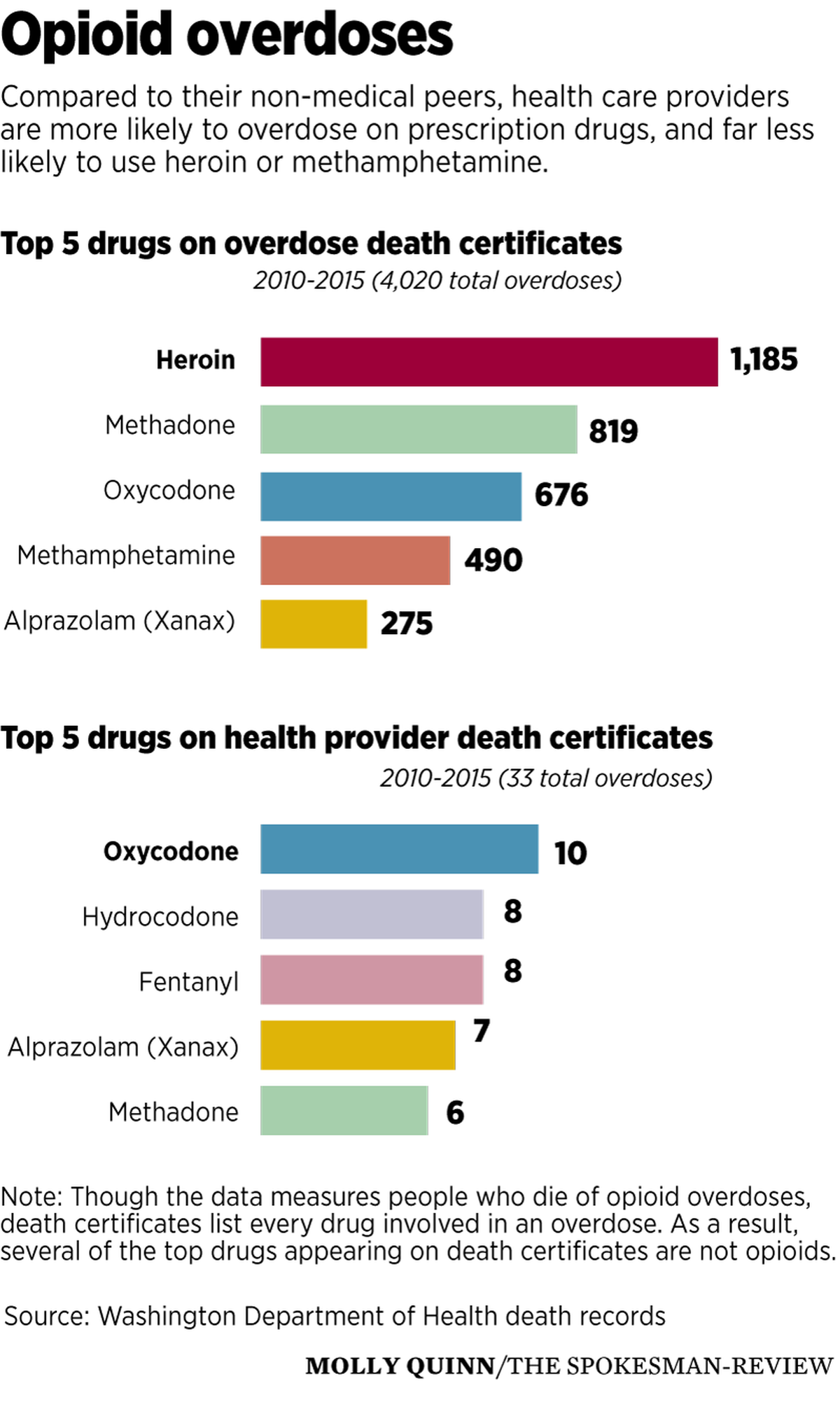

A Spokesman-Review analysis of Washington death records, health care provider licenses and Department of Health disciplinary records found at least 33 medical professionals in the state have died from opioid overdoses from 2010 to 2015, the most recent year that overdose death data is available.

Most of the deceased are not physicians. They’re nurses, pharmacy technicians and, in some cases, chemical dependency counselors.

None were disciplined by the Department of Health for suspected drug or alcohol abuse or diversion before their deaths, records show, though a Cowlitz County nurse died in 2014 before a pending investigation into his drug use could be completed. His death certificate listed nine drugs, more than any other professional on the list.

Two others were reported, but both had their cases closed. A Port Townsend nurse practitioner had a complaint of drug and alcohol abuse, falsifying records and mental disorder dismissed in 2010 due to insufficient evidence. She fatally overdosed in 2015 with fentanyl, morphine and hydrocodone found in her system.

A Longview chemical dependency counselor accused of drug or alcohol abuse in 2011 also had his case closed with no recorded discipline. He died of a heroin overdose in September 2013.

Most overdose deaths are quiet

Some of the deaths made headlines. A Tacoma doctor, Nick Uraga, had been charged with kidnapping and harassing his ex-wife shortly before he was found dead in his Gig Harbor home of what was described at the time as an apparent suicide. The medical examiner later ruled it an accidental drug poisoning with oxycodone, according to his death certificate.

But most, like Beth Cleveland’s, went unnoticed outside of the family, friends and coworkers struggling to make sense of a sudden death.

The deceased include a Wenatchee-area hospital pharmacist who died at 58 with six prescription drugs, including methadone and hydromorphone, in her system. A Mukilteo pharmacy technician, devoted Irish-Catholic and diabetes advocate, died at 34 from a hydrocodone overdose.

Almost none used heroin or other illegal drugs, a marked contrast to the 4,020 Washingtonians who died of opioid overdoses during the same time period.

Heroin is by far the most common drug on death certificates, and methamphetamine is in the top five statewide. But medical professionals tend to use prescription painkillers. Oxycodone, hydrocodone and fentanyl top the list.

Without exception, the obituaries do not mention a cause of death. They speak only of people who “passed away suddenly,” often leaving behind surviving parents, siblings, spouses and children.

Violet Smith, a nursing assistant from Colfax, is among the few who were commemorated. Smith, 33, died January 6, 2015, with an unprescribed fentanyl patch on her back and morphine in her system. Fentanyl is a powerful painkiller about 80 times stronger than morphine.

Smith had worked at Paul’s Place, an assisted living facility, before her death. Her supervisor, nurse Chanda Jones, said Smith was a dedicated worker.

“She loved her people, took good care of them,” Jones said. The residents affectionately named her “Duckie” because of the way Smith waddled around when she was pregnant.

The Moscow-Pullman Daily News featured her in a series about Whitman County residents younger than 50 who had died.

Smith’s twin sister, Valerie, told the Daily News her sister was struggling with painful acid reflux and had sustained an injury while trying to help a patient who’d fallen.

Jones said staff suspected she might have been struggling. Smith was open about the fact she’d abused drugs in the past and had been calling in sick to work more and more during the last year Jones worked with her.

But her death still came as a shock. Jones said nobody was sure where she got the fentanyl.

“We didn’t have anybody at our facility who used those, so who knows where she got them,” she said.

Smith left behind two young sons after her death.

Easier access to prescription drugs

Cleveland said her mother’s nursing license made it easier for her to get hydrocodone prescriptions, even as doctors were cracking down on the availability of powerful pain medication.

“She knew what to say and how to say it,” Cleveland said. “Knowing that she was a nurse, they didn’t question her at all.”

Beth’s prescribing nurse practitioner, Susan Bowen-Small, had her license suspended by the Department of Health in February 2014, almost a year and a half after Cleveland’s death. Three of her patients had died after taking painkillers she prescribed, according to the Department of Health, between January and March of 2013, after Beth was already dead.

The medical profession has long struggled with how best to handle providers struggling with drug addiction.

Though doctors, nurses and pharmacists are among the people best-equipped to see the consequences of drug addiction, they’re also susceptible to drug abuse thanks to an intersection of factors: high-stress jobs, odd hours and a belief that they know how to stay in control of the drugs they prescribe or administer routinely.

Doctors with an addiction problem tend to abuse alcohol most frequently, said Chris Bundy, the director of the Washington Physician’s Health Program, which helps doctors get treatment for addiction and mental illness.

Nurses are far more likely to abuse opioids or other prescription drugs. Most seeking treatment in Washington through the Department of Health have either an opioid addiction or an addiction to multiple substances, including opioids.

“A lot of that is because they have direct hands-on access to those medications,” said John Furman, director of Washington Health Professional Services, a group within the Department of Health that treats nurses for drug addiction.

Cleveland’s father married Beth when Cleveland was about 9, when the family lived in Southern California.

Though Cleveland mostly lived with her mother, she saw Beth regularly and grew closer to her as the years passed.

Cleveland believes Beth’s addiction started shortly after her marriage, when her migraines began getting worse. She would be in so much pain that she’d have to sit in the dark in bed all day, unable to look at lights or a screen.

“They tried everything. They went to multiple neurologists and doctors. They tried acupuncture, they tried naturopaths,” Cleveland said.

Cleveland believes it’s possible another option could have worked in the long term, if Beth had stuck with it. But pain pills provided immediate relief, and she had doctors willing to write her prescriptions.

“Those are extremely addictive and she already had an addictive personality,” Cleveland said.

She believes Beth’s childhood contributed to her addiction, causing her pain she never fully dealt with.

Her dad died when she was young, and her sister also struggled with drug and alcohol addiction. Her mother liked to play favorites, which made her childhood difficult, Cleveland said.

Art and fantasy helped her. She loved “Lord of the Rings,” “Harry Potter” and other books that let her escape into new worlds. But sometimes, that wasn’t enough of an escape.

In retrospect, Cleveland said Beth’s addiction was worse than her family wanted to believe.

“We knew she had a problem when we were fairly young,” Cleveland said. As a child, she remembered being told Beth wasn’t feeling well or had a headache for days when she’d be sick in bed.

In 2011, Beth had a grand mal seizure at work while she was in California and lost her driver’s license for six months as a result. She told Cleveland it was from her pain medication: she’d taken three or four pills when she was only supposed to have one at a time.

“That should have been another red flag,” Cleveland said.

Beth went to rehab once in Napa, California, and had periods where she’d try to get better or kick her addiction.

When she moved to the Spokane area, she lived with Cleveland in Rosalia while searching for her own place. A few days into her stay, she hadn’t come upstairs all day. Cleveland went to check on her and found her in bed, watching Netflix and saying she had a migraine.

Cleveland had leftover pills from a hydrocodone prescription when she’d gotten knee surgery in 2012.

“She found out I had them and came up and said, ‘Hey, do you think I could have a couple pills?’ ” Cleveland remembered. She gave her stepmother two.

“A couple of hours later, she was asking for more,” Cleveland said. Eventually, she had to lie and tell Beth she’d run out.

Carrot and stick approach

State law requires medical providers – anyone with a Department of Health license – and health care employers to report license holders who are unable to work “with reasonable skill and safety due to a mental or physical condition,” including drug or alcohol addiction. Providers are also supposed to self-report.

A total of 558 health care providers were sanctioned by the health department from 2010 to 2016 for drug or alcohol violations, and the department took 1,023 reports of suspected drug and alcohol violations involving 843 individual providers during the same period, according to data obtained through a public records request.

Washington Health Professional Services takes a carrot and stick approach to suspected substance abuse among nurses, including nurse practitioners.

WHPS, a part of the Department of Health, handles referrals from family, colleagues and nurses themselves who may be struggling with drug addiction.

If the program finds a nurse is abusing drugs, they’ll be put on a monitoring agreement and be expected to comply with a treatment program. If they comply with counseling, group therapy and pass drug tests, they’ll be able to keep their license and continue practicing once it’s deemed safe.

“If they’re successful in the program, the nursing commission will never know that they participated and that’s an incentive,” Furman said.

That’s the carrot. The stick? Screw up, and the program can report nurses to the nursing commission for non-compliance, and they could lose their licenses and jobs.

A similar program exists for doctors: the Washington Physician’s Health Program. Unlike WHPS, it’s completely independent from the Department of Health, and deals with any issue making it difficult for a doctor to practice safely, including mental or cognitive illnesses.

“We want to encourage early intervention and treatment without creating a safe harbor for people who are potentially putting patients at risk,” Bundy, the program director, said.

The physician’s program has a higher success rate than the nurse’s, but providers in both fare better than the general public in addiction treatment.

During the 30 years the doctors’ program has existed, 81 percent of graduates have stayed clean after five years, based on random drug tests, Bundy said.

Among nurses who graduate, an average of 79 percent were employed in 2017, according to the program’s annual report. Fewer than 1 percent of nurses who graduate return to monitoring later for new violations.

Typically, 40 to 60 percent of people treated for drug addiction will relapse, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the federal government’s main funder of addiction research. They define relapse as “recurrence of symptoms that requires additional medical care.”

Still, many health care providers already fear reporting colleagues out of concern that they’re “tattling” or going to get someone in trouble.

And reaching out for help remains difficult, even when nurses and other professionals are aware of resources.

Anne Mason, director of Washington State University’s doctoral program in nursing, said nurses are aware of WHPS and are taught that anyone, from any background, can become addicted to narcotics.

But that’s not always enough to make people willing to seek help.

“There’s so much stigma around addiction whether you’re a health care professional or any other professional,” Mason said. “There’s oftentimes a message that addiction is about people making a choice, a bad choice, and people could choose not to be addicted if they wanted to but they don’t want to.”

Jones said in her career as a long-term care nurse, Smith is far from the first professional she’s seen struggle with addiction.

Nursing is stressful across the board, regardless of the type of nursing someone is doing, she said. For long-term care nurses like her, it’s hard becoming close to patients and watching them have bad days or go downhill.

“They become family so when they’re not doing well, we’re not doing well,” Jones said.

The idea that nurses should know better keeps them from seeking help.

“As a nurse you have a certain amount of pride and responsibility, and to go to someone to tell them you’re having a problem or in the weeds a bit, it’s just not done,” Jones said.

Those concerns may be heightened because the nurse’s program is part of the Department of Health, not an independent group.

“I think that there’s fear and that fear is heightened when there appears to be less of a separation of church and state,” Bundy said.

Most reports of drug abuse to both the physicians’ health program and the Department of Health don’t result in discipline or monitoring.

“We often hear after the fact that there were others who knew that individual, often several others, who knew that individual and had a concern and failed to act,” Bundy said.

In 2016, Bundy said they had 216 people referred to them and had 70 end up in monitoring agreements. In 2017, they had 189 referrals and 80 monitoring agreements. Most doctors are able to return to work.

WPHS, the program for nurses, had 371 nurses participating in the program for some part of 2017, and 83 new nurses sign monitoring agreements.

Searching for the right intervention

Cleveland tried to help her stepmother, Beth, more times than she can count. Though she’s a phlebotomist and works in the medical field, she said she didn’t know there was a program that treated nurses, or anywhere she could have called for help.

Beth often lied to her husband, Cleveland’s father, about her drug use. She would say she wasn’t taking pills anymore and went to different doctors to get prescriptions, not telling them what she was getting elsewhere.

“She was trying to hide it from my dad, she was trying to hide it from everyone,” Cleveland said.

On the day she died, Cleveland believes Beth had a migraine and just kept taking pills.

“She probably took the initial medication and it didn’t work, and you’re loopy anyway so you just keep taking it,” Cleveland said.

Her death certificate would list three drugs: hydrocodone, Xanax and benadryl, as contributing to her death.

After her stepmother overdosed, Cleveland said she didn’t sleep for about a week. She couldn’t forget seeing the body of someone she loved looking so empty.

Cleveland still keeps Beth’s paintings at home, and remembers how much Beth loved to decorate for holidays.

“She had decorations for every holiday under the sun. She has dish towels, I mean. Everything,” Cleveland said.

At times, it’s hard for Cleveland not to see Beth’s death as a betrayal of her father and the rest of her family.

Sometimes, she thinks nothing could have saved Beth. But maybe the right intervention – from the nursing commission, or a co-worker, or someone – could have helped.

Sometimes, she blames herself for not doing more.

And sometimes, she’s left with the thought that she knows doesn’t capture the full picture, the thought that has made addiction such a taboo topic in the medical field.

“As a nurse, she should have known better.”