Bighorn sheep herds inter-mingling in southwestern Montana

CAMERON, Mont. – If there’s anything better than seeing a bighorn ram, horns fully curled, it’s seeing 12. The number seemed to keep growing on a recent morning here, the tan bodies of wild sheep standing out against the steep white slope at the southern end of the Madison Range.

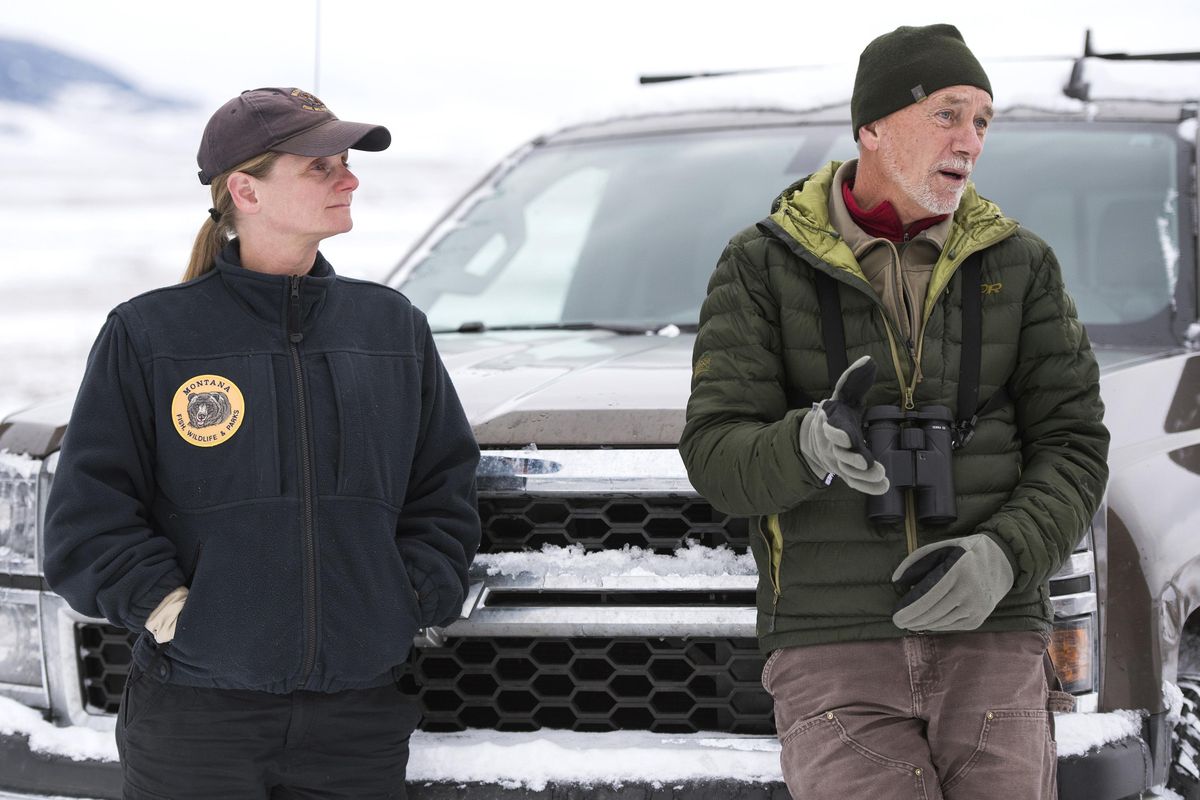

Ewes and lambs were grouped up. Rams were interspersed throughout, and some wandered around alone, looking every bit majestic. And, every time it seemed they’d been counted, Julie Cunningham, a biologist for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, spotted another.

“They just keep popping out of the sagebrush,” said Cunningham, grinning.

Cunningham, who has worked for FWP for 12 years, is the person in charge of this sheep herd that lives near Quake Lake, known as the Taylor-Hilgards herd. It’s a small part of her job. She’s the area biologist for the Bridger, Gallatin and Madison mountain ranges. Elk, deer, bison and pronghorn compete for her time alongside these sheep.

The herd numbers about 200, and it’s the source of one of her recent successes. She organized a series of transplants over the last few years, starting with 52 animals in 2015 and adding more with transplants in 2016 and 2018. They released the sheep in the Wolf Creek drainage, just a few miles north and in the mountain range’s western foothills.

She hoped the sheep would explore some new country, maybe find new winter range in historic but unoccupied sheep habitat. Maybe they’d go interesting places. She didn’t know.

So she was excited when she spotted one of them on the side of U.S. Highway 191, on the other side of the mountains.

She and a colleague were in the Gallatin Canyon to euthanize a moose. On the way back, she spotted an orange ear tag among a group of sheep, members of the Madison Range’s other sheep population, known as the Spanish Peaks herd. She had attached orange tags to the sheep she moved in 2016. They turned around and had a closer look.

It was indeed Orange Ear Tag No. 11, one of the 2016 transplant animals. Somehow, it zipped over the Madison Range and had started hanging out with the Spanish Peaks sheep. Its adventure connected two native sheep herds previously separated by miles of rugged, sheep-free country.

The connection is double-edged for Cunningham, both anxiety and triumph. In the short-term, she’ll watch closely to see if the connection has any negative effects, such as the transmission of disease from one herd to the other.

But it’s also the closest the range’s sheep populations have been since the mass decline of the species, and Cunningham can imagine a future where the animals are more widespread in the Madison Range.

“In the long run, seeing sheep use the whole mountain range could mean great things for sheep conservation,” she told the Bozeman Daily Chronicle.

The story of wild sheep is not unique. There were many and then there weren’t, due to a combination of westward expansion, overhunting and disease.

There still aren’t very many. In Montana, there are a little more than 6,000 total. Surprises like one sheep crossing a mountain range and making new friends are welcomed by conservation advocates and wildlife managers alike, as recovering the species has proven challenging both biologically and politically.

Bob Garrott, an ecology professor at Montana State University, said the low point was somewhere between the turn of the 20th century and the Dust Bowl. But, while there has been some successes, conservation efforts haven’t brought the animal back in the same way they did for some other species.

Garrott said that can be attributed to differences between sheep and other species. For one thing, they don’t tend to redistribute themselves when they’re doing well, often ending up in large numbers in small areas.

“That’s an inherent behavioral trait,” Garrott said. “In conjunction with that is the exotic pathogens that have been introduced to bighorns from domestic livestock.”

Respiratory disease outbreaks caused by those pathogens have decimated several bighorn herds. It’s happened to both herds in the Madison Range within the last 30 years, according to FWP’s 2010 Sheep Conservation Strategy. Some herds recover well, like those two. Others didn’t.

The danger of domestic sheep introducing new diseases to their wild cousins holds enormous sway in the management of bighorns. As a result, managers focus on keeping the wild and the domestic completely separate to keep bighorns from contracting sheep-killing pathogens from their domestic cousins. That need for separation can also make it tough to restore sheep.

“A challenge we’ve had in bighorn restoration is finding safe places to put sheep,” said Gray Thornton, of the Wild Sheep Foundation.

Thornton is careful to say that the foundation doesn’t want to harm the domestic sheep industry, but he acknowledges they are part of the reason it’s hard to find places for wild herds. His organization tries to work with landowners on restoration, and he wants the industry’s help in restoring the animal.

And, he said, some ranchers are all for it.

“I’ve spoken to some of the sheep producers that get it,” Thornton said. “They want more bighorns on the landscape. We want more bighorns on the landscape. We don’t want to put the domestic sheep off the landscape.”

The movement of sheep in the Madison Valley didn’t present any major conflicts with the domestic sheep industry, with no large herds in sight. The conflict did surface in an area west of there, with an early 2000s reintroduction in the Greenhorn Mountains.

The Greenhorns are on the northwest side of the Gravelly Range, a largely remote set of mountains southwest of Ennis. John Helle, a third-generation sheep rancher from Dillon, trails sheep into the Gravellies each year from their ranch in the Beaverhead Valley. His operation is one of the largest in the state, and it also produces the wool behind the clothing brand Duckworth, which has offices in downtown Bozeman.

When Helle first heard about the Greenhorn reintroduction, he was opposed. He said he worried it could invite litigation against his operation and his federal grazing leases, which are just one piece of the ranch’s 100,000-acre grazing system.

But he also believed he might be able to work with FWP and conservationists to find ways to protect both domestic and wild – like keeping them separate.

“We can argue about the science all day long. But we can come together and say right now, ‘I think separation is a good thing,’ ” Helle said. “We don’t have a problem with bighorn sheep.”

They worked it out, and, in 2003 and 2004, FWP moved a total of 69 sheep into the range.

In Helle’s eyes, it’s gone well. He’s been in regular contact with the FWP area biologist, and he was happy to see the state offer a hunting tag for the herd this year.

But, at the same time, a wildlife group in Bozeman has said the herd isn’t doing well enough. The Gallatin Wildlife Association sued over Helle’s grazing leases in 2015, arguing the public land grazing is a threat to bighorns and grizzly bears. The group also argued against the hunting proposal for the Greenhorn herd, arguing that the herd has declined – the last count was just over 40 – and is too small to support hunting.

“I cannot believe more people aren’t waving red flags,” said Glenn Hockett, the group’s president.

Hockett also argues the state has ignored the best science in its management strategy, which defines a “minimum viable population” of bighorns as 125 individuals. He points to research suggesting that herds need more than 1,000 animals to have a chance of long-term survival. The association filed a petition with the Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission raising that issue and calling for a repeal of the hunt.

The Wild Sheep Foundation isn’t on Hockett’s side. One of the foundation’s biologists wrote a letter to the Fish and Wildlife Commission opposing Gallatin Wildlife Association’s petition. The foundation also disagrees with the group’s attempts to end grazing in the Gravellies, arguing that the Greenhorn reintroduction has been a success.

Hockett sees the Wild Sheep Foundation’s rebuke as an attempt to marginalize him.

“They’re marginalizing people who want the law followed and the science applied,” Hockett said. “That’s what we want.”

Helle, on the other side, thinks Hockett’s approach is “too divisive,” and won’t succeed in accomplishing anything. He also wonders whether the noise around the Greenhorns discourages other ranchers from working toward wild sheep conservation.

“It’s a mess,” Helle said. “No one’s going to want to sign up for this.”

The two herds in the Madison Range have been there forever. Though FWP has augmented both at times, they were never fully extirpated. Even disease couldn’t knock them out.

Harry Liss hasn’t been here forever. He lives along the Madison River near Raynolds Pass, in the area that’s frequented by the Taylor-Hilgards sheep. He’s been there since 1994. He also owns a piece of property above the highway, too – one of the places Cunningham used for a trap site for the sheep transplants.

Liss remembers the die-off of 1997. He recalls counting 84 sheep around there. The state’s sheep plan said the herd was between 20 and 30 animals after the die-off. But Liss wasn’t worried.

“I knew they were gonna come back,” Liss said.

That’s what they did. The population has since ballooned to its current size, leaving enough for the transplant project.

People would like to see the transplant here duplicated elsewhere, though there’s nowhere that’s perfectly analogous. It wasn’t complicated by any large domestic sheep operations, though there are some small “hobby herds” in the area. And, Cunningham did have to gain support from area landowners before anything could happen.

Still, Garrott, the MSU professor, thinks it’s only a matter of cooperation between everyone involved.

“There’s no reason we can’t do that,” Garrott said.

Cunningham is content letting others worry whether that’s possible. In the meantime, she’s still enjoying watching what her sheep do. She saw Orange Ear Tag No. 11 twice in October. Using other tools, she can track other trends, like the sheep that have moved into the creek drainages that neighbor Wolf Creek.

Surprises abound, like the pair from the same transplant group that went opposite directions, according to her data.

“They were in the same trailer, they were under the same net. They could have been sisters. I don’t know,” she said. “One of them ran up to the Wedge, which is a 10,000-foot peak, and lived on windblown slopes for the rest of the winter. The other one hung out outside a guy’s house on his porch.”