Getting There: Say Hello to the new Foley Highway

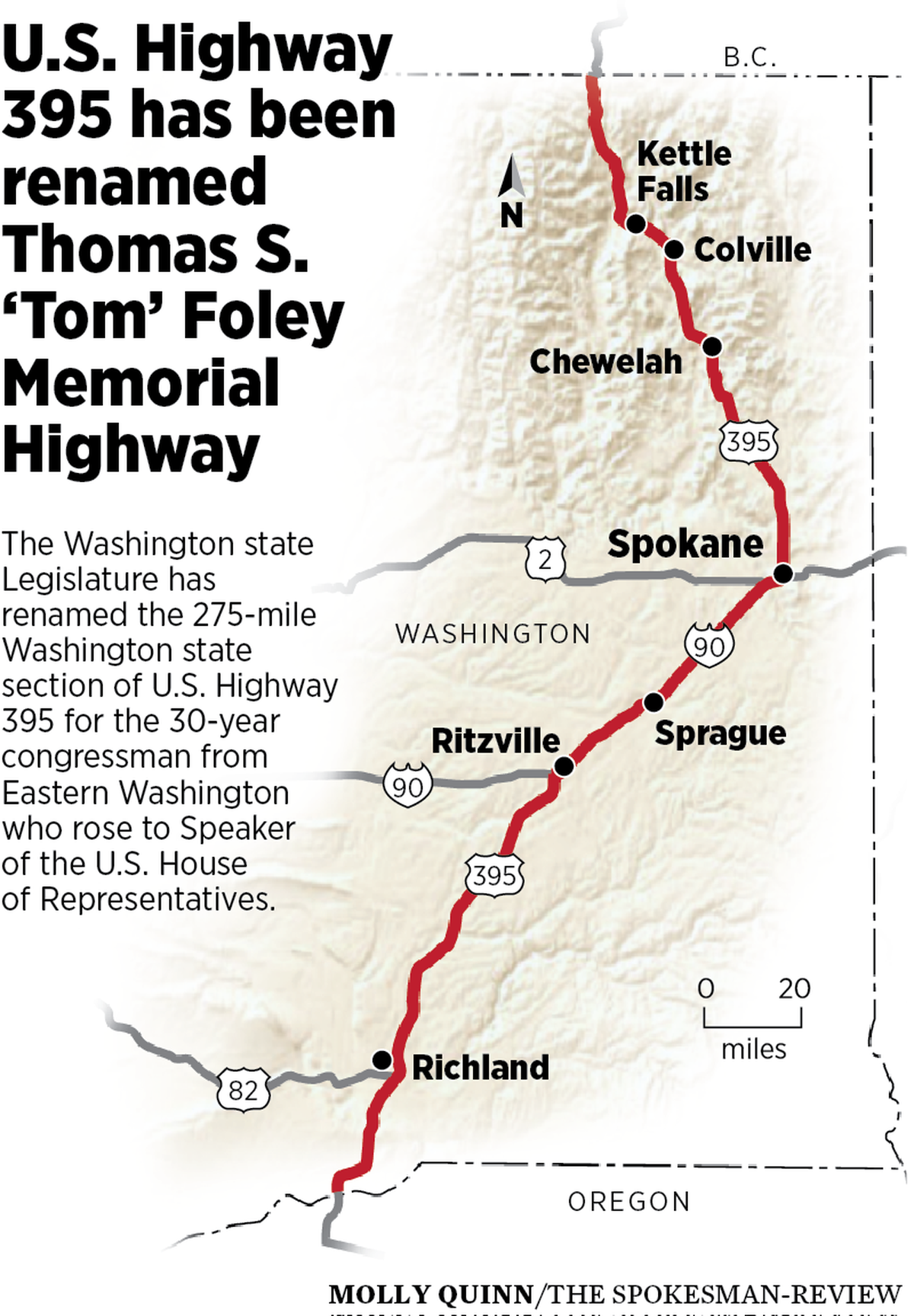

U.S. Highway 395 in Washington state is now called the Thomas S. “Tom” Foley Memorial Highway following a vote by the Legislature this year. (Courtesy Washington state Department of Transportation)

Today, it’s no longer U.S. Highway 395. From now on, we’ll call it the Foley Highway.

Officially, it’s the Thomas S. “Tom” Foley Memorial Highway, but that mouthful surely won’t last. The renaming of the highway, to be done in a ceremony with some muckety-mucks near Spokane’s University District this morning, only applies to the 275-mile section of the route in Washington state, part of an interstate highway connecting Canada to Mexico.

And that’s fine, considering this was Foley’s territory. Born and raised in Spokane, Foley went into law and Democratic Party politics, eventually serving 30 years as Eastern Washington’s congressman and, notably, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, the position currently held by Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis.

Foley, who also has the imposing federal building in downtown Spokane named after him, was an influential politician who had a reputation for delivering for his constituents. As his 2013 obituary in the Spokesman-Review noted, “One person’s pork, Foley used to say, was another person’s wise investment in the local infrastructure.” We can thank Foley for the expansion and transformation of Fairchild Air Force Base and the Centennial Trail. People still credit him for the city’s skywalk system, but his was not the vision behind the second-story pedestrian ways.

However, when it comes to 395 – the Foley Highway – he was transformational.

When state legislators agreed to rename the road earlier this year, they pointed to Foley’s work securing the money to turn 395 between Ritzville and the Tri-Cities into a four-lane, concrete highway. Under his guidance, Congress allocated $54.5 million to widen the road as part of a 1991 highway bill. The National Highway System chipped in another $10.4 million and the state paid $17.9 million.

Before the work, with just one lane in either direction, that section of highway was considered one of the state’s most dangerous roads. Countless lives have been saved thanks to Foley’s “pork.”

The road named for Foley is now one piece, but its sections were built separately over decades, and its cobbled-together past gives it a circuitous route as it shares pavement with other highways and interstates.

In 1932, the state expanded Spokane’s “superhighway,” and connected Spokane to the Colville highway. The road shot northwest as a spur off the Inland Empire Highway, one of the state’s first automobile routes. American life was increasingly defined by the personal automobile, not to mention commerce, and the spur came in the midst of government spending on infrastructure to combat the detrimental effects of the Great Depression.

Still, the way to Colville was nothing new.

A 1932 Spokesman article told of the route’s precursor, a trail developed by the indigenous people of Eastern Washington later used by fur traders and missionaries.

Francis Wolff, an early white settler in the region, is credited with opening the first modern store in Colville when he transported a stock of merchandise there from the Dalles, in Oregon.

“This was the first time goods were carried to Colville by wagon – in the winter of 1856-57,” Wolff wrote in his autobiography. “I stopped about five miles north of the present town of Colville.”

His wagon tracks were followed three years later by Maj. Pinkney Lugenbeel when he established the military post, Fort Colville.

As mines and logging operations pumped out their products, a merchant named W. P. Winans declared it “necessary to make a road from Cottonwood creek, a few miles south of Chewelah, to Peone prairie, a distance of about 60 miles through the timber.”

In 1867, that road was completed by an army of volunteer laborers, connecting Chewelah to what is now just northeast of Spokane, near Mead and Green Bluff. In 1881, the U.S. Army’s First Cavalry Regiment sent a detachment to improve and repair the road. A man named Captain Hutter, with the cavalry, “camped at a beautiful lake on the divide, and on account of the numerous loons named it Loon Lake,” according to the Spokesman.

Just a few years later, John Glover, the brother of the controversial “father” of Spokane James Glover, and Lane Gilliam, a deputy sheriff who ran a livery stable with Glover at what is now Spokane Falls Boulevard and Howard Street, operated a stage coach to Colville.

The trip took three days. One way.

Soon enough, though, cars supplanted wagons, and pavement became every motorist’s best friend. When the state Highway Department was created in 1905, there were 1,082 miles of roads controlled by the state, but only 125 miles were “improved” with pavement. Four years later, the Highway Department took some control of road construction contracts and formally made the decision that highways should be paved. In 1911, the Permanent Highway Act was passed, granting even more control regarding how highways were built to engineers in Olympia.

From then on, road building moved quickly, including the sections that would become the Foley Highway. The state’s gas tax was instituted in 1921 at one cent per gallon to fuel the construction of roads, and from there the tax ticked up quickly: to two cents per gallon in 1923, three cents in 1929, five cents in 1931 and on. The speed limits for highways also went up, from 30 mph to 40 mph in 1927.

The era of fast-moving, unimpeded driving had arrived in Washington state, and highways were here to stay and expand. In 1926, the Joint Board on Interstate Highways formalized the United States Numbered Highway System, giving us the integrated network of roads and highways we use to this day, the interstate system notwithstanding. U.S. Highway 395 was born, cobbled together from many existing roads.

In 1929, Foley was born, the son of a school teacher and Superior Court judge. During his youth, and much like today, the highway that would be his namesake ran through the middle of Spokane. Back then it ran northbound on Monroe Street, crossing the Monroe Street Bridge, to Garland Avenue, where it headed east to Wall Street, Waikiki Road, Mill Road, Dartford Road and North Lane before joining the present-day route of the highway in Wandermere.

In 1937, the highway was shifted east, to its current route up Division Street.

Over the course of the next decade, the old highway will shift east once again, with the completion of the $1.5 billion North Spokane Corridor. The otherwise known north-south freeway has been contemplated since Foley was 17 years old. He worked for the highway department during his summer break from Gonzaga University. He later supported the highway’s construction in Congress, so much so that the Spokane City Council voted to name the north-south freeway after him in 2015.

Then the Legislature did the city council one better. Instead of the ten mile stretch of new highway in Spokane after him, it named the entire state section after him. Former Sen. Michael Baumgartner, R-Spokane, tried to derail the effort somewhat. His amendment to name the part from Spokane north for the late Sam Grashio, a highly decorated Spokane soldier who survived the Bataan death march in World War II, was voted down.

Foley lost re-election during the Republican wave of 1994, becoming the first sitting Speaker of the House to lose a bid for re-election since 1862. This defeat will stick with him in the history books for a long time to come. But for motorists, Foley may be remembered in the future as a highway, both storied and brand new.

School’s in, slow it down

School begins this week for most Spokane students, so there’s no good reason not to slow down.

First, for safety’s sake, watch out for children walking to school and other pedestrians. Your car is 4,000 pounds. They weigh in at like 40.

Second, it’s the law. Enforcement of the 20 mph speed limit around all schools will be stepped up, not to mention the numerous speed cameras the city has set up around area schools.

In related news, the city will begin removing summer season speed limits signs around public swimming pools and parks.

Sewer work goes on and on

The city’s years-long effort to stop sewage and stormwater from dumping into the Spokane River continues to effect commutes.

For work near the Adams Street project building a huge 2.4-million gallon underground tank, First Avenue between Walnut and Jefferson Street is closed. Sprague Avenue between Jefferson and Cedar is also closed.

The East Riverside project in Spokane’s East Central neighborhood has closed Riverside Avenue between Lee Street and toward Crestline.

The Liberty Park tank work keeps Fifth Avenue closed between Perry and Arthur. Third Avenue is reduced to one lane between Arthur and Liberty Park Place.

In Peaceful Valley, work has completely closed Main Avenue from Monroe to Cedar streets, Cedar from Main to Water Avenue, and Water from Cedar to Ash Street.

The massive 2.2-million tank being constructed by the library on Spokane Falls Boulevard still has Spokane Falls closed from Lincoln to Monroe.

Grind and overlay

The city’s street department will be out doing some heavy maintenance starting today through Wednesday, Aug. 29. Work will be done on Havana Street from Second to Third. On Thursday, Aug. 30, they’ll shift to 16th Avenue from U.S. Highway 195 to Lindeke.

Work is also being done on Division Street and Manito Boulevard, from 33rd to 37th avenues, and on Fifth Avenue from Freya to Havana.

Work continues across the city

Major work on some of the city’s major roads goes on. Various projects on High Drive, Martin Luther King Jr. Way, North Monroe, Sharp Avenue and Sunset Boulevard continue to have major impacts. Avoid them.

In the Valley

Work to reconstruct the Broadway Avenue intersection is expected to be complete by Sept. 15. Single lanes are closed on Mullan and Argonne roads.

Mission Avenue is closed between Flora Road and Sprague Avenue until the end of October.

The intersection of Pines Road and Grace Avenue is getting reconstructed, closing one lane of Pines and Grace at the west leg of the intersection. Work should be done by the end of the month.

Both directions of Sprague between Fancher Road and Dyer Road will be largely closed between 7 p.m. and 6 a.m. this Wednesday, Aug. 29. One lane in either direction will remain open to traffic.