Farmers bear burden of making Washington king of the cherry

WENATCHEE – Convoys of headlights looked like glowworms in the predawn darkness Thursday morning as migrant workers coaxed aging vehicles up more than 1,500 feet of switchback roads to hilltop orchards above, one last great push in the harvest of the nation’s largest cherry crop.

Parking in the dirt, the workers milled about, waiting for Michelle Gutzwiler to hand out the cards that would track how many boxes each picker would fill. The cards, workers, boxes and vehicles made up the last act in Gutzwiler’s great annual gambit: that the previous eight months of work would pay off.

“Our expenses and equipment costs are over $100,000. Our bills are due in October,” she said. “But we won’t know how we did until we get paid in November. I can cry and beat on doors, but it doesn’t come any faster.”

Gutzwiler is just one of scores of cherry producers who make Washington the king of the succulent but temperamental fruit. Of the 61,000 acres under cherry cultivation in the Northwest, some 69 percent produce fruit in the Evergreen State.

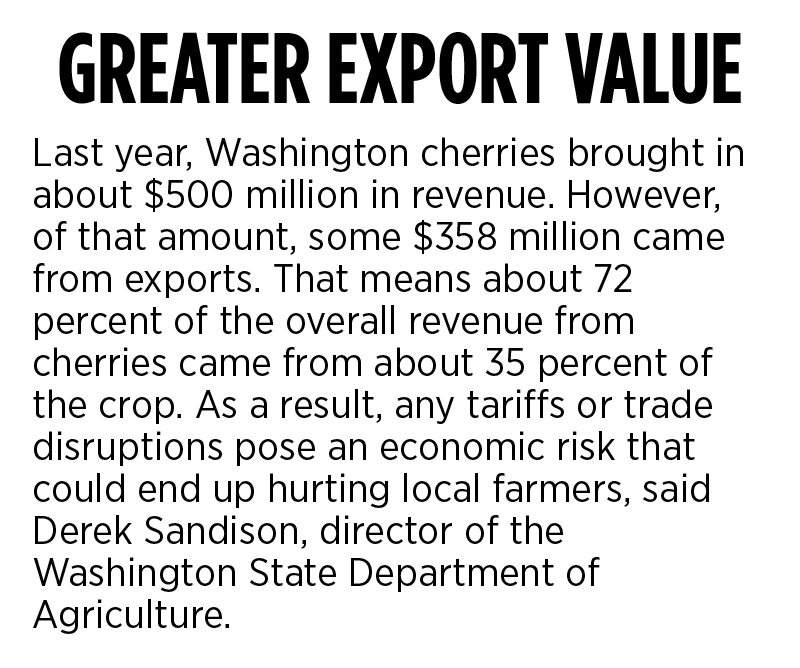

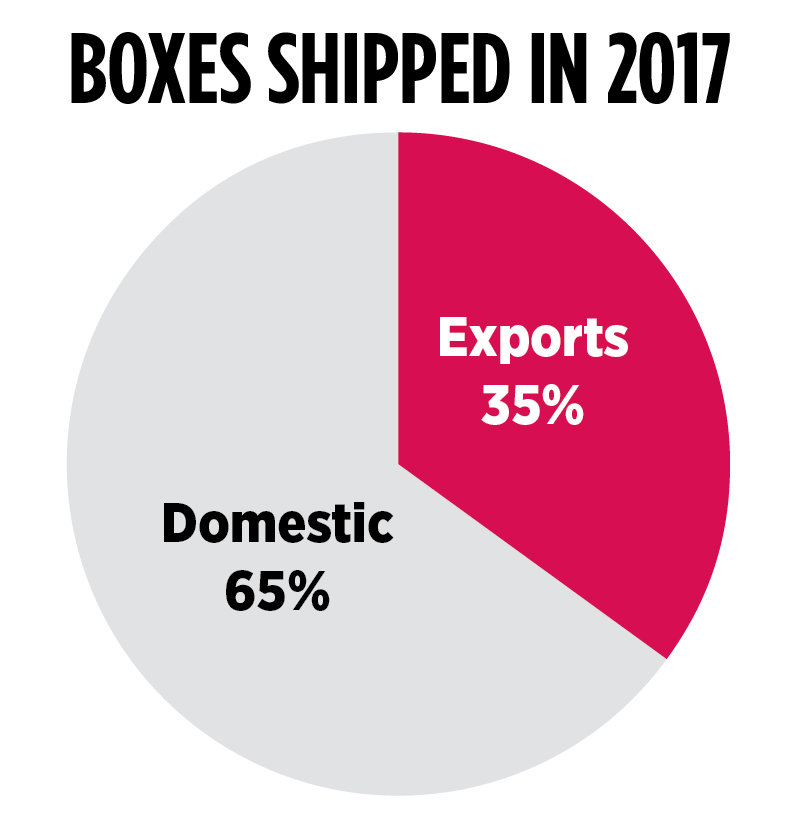

Washington farmers produce more than double the tonnage of sweet cherries of the next two leading states, Oregon and California, combined. Derek Sandison, director of the state Department of Agriculture, said Washington cherries represent a half-billion-dollar industry, and are the No. 6 cash crop for the state.

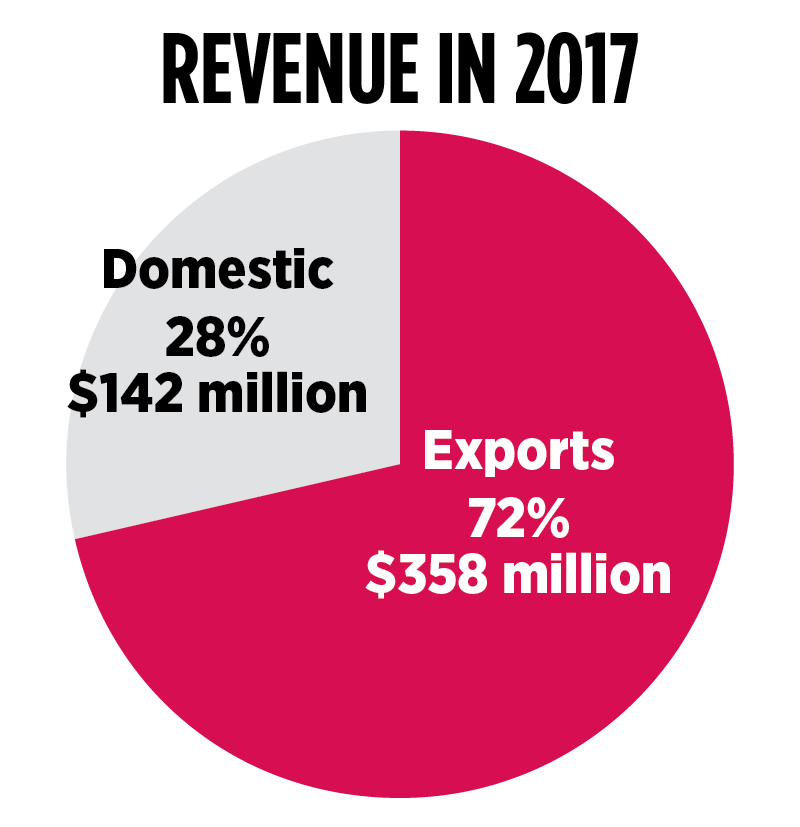

However, of that amount, some $358 million came from exports, meaning about 72 percent of the overall revenue from cherries comes from the 35 percent of the crop sold on international markets. As a result, any tariffs or trade disruptions pose an added economic risk that could end up hurting local farmers, Sandison said.

“Historically, one of the reasons we have been able to compete so well in export markets is because we have a good reputation for the quality of our cherries,” he said.

But it’s also a crop that can crash with a single wind event or hailstorm. Once farmers get their cherries to the finish line, their paychecks rely on a market rocked by trade wars over tariffs and other marketing decisions that are out of their control.

“In my mind, farmers take the biggest risk out of everyone who takes a piece of that pie. The warehouse, the marketers, the truck drivers and the shippers all get paid regardless. But we work all year to make this crop,” Gutzwiler said. “They never work for an entire year and then lose it all.”

Jorge’s opportunity

Gutzwiler grew up in East Wenatchee with the goal of getting out of her hometown. She didn’t make it far.

In 2000, she married Jake Gutzwiler, who works as a quality control manager at Stemilt, a fruit company that operates a warehouse in Wenatchee.

She stays home with their three children and runs the picking crews on the 23 acres they’ve planted, mostly with Sweetheart cherries, which are larger and later-maturing than their cousin, the more abundant Bing cherry.

While she’s embraced the role of a farmer’s wife, Gutzwiler said she’s never fully learned to deal with the uncertainty.

“I’m married to a wonderful man. I knew that was part of the deal,” she said. “On our wedding day, I said yes to the man and yes to the way of life.”

Farming cherries includes pruning the trees in the winter, which Michelle is barred from doing. The work is supervised by Jake, who has a master’s degree in horticulture from Washington State University.

But the couple also must pay for fuel costs to operate wind machines that move cold air to prevent frost from killing cherry blossoms. They also must pay to spray insecticides to keep a host of bugs from eating what they hope to sell.

Add in the normal living costs, like paying for the home they purchased from father-in-law Norm Gutzwiler in Wenatchee Heights, and finances can cause some stress.

“There are so many years that you don’t make any money. But it teaches them how to work,” she said, referring to her three children. “That’s why we have the orchard. They will be so much better off in the long run.”

Growing up in the area, Gutzwiler said her father barred her from working in the orchards with men from out of the area whom she didn’t know.

“I had friends in high school who went and picked in the orchards,” she said. “But I haven’t had a single kid (from Wenatchee) ask to pick.”

Instead, each year, the family relies on temporary workers from Mexico. Many of them start the season picking cherries in California. They move to the Tri-Cities, where cherries mature faster, and then they move north to Wenatchee for the late cherries and the beginning of apple season.

The Gutzwilers’ best picker is Jorge Bacquez, 29, of Chiapas, Mexico. Last year, he made his personal best by picking seven 330-pound bins of cherries in one day. Paid $60 per bin, Bacquez picked five bins each on Thursday and Friday, which was by far the most of any picker.

“He’s one of the best workers I’ve ever had,” she said. “He’s respectful. He’s gentle on the tree. He’s just good all the way around.”

Bacquez said he’s been coming to the United States for work since 2008. He started working in Pasco in May and came north for the later cherry season in Wenatchee. He will leave again for Mexico in October when the apple picking is done.

For the season, Bacquez earns $20,000 to $22,000, which he said he will use to support four other family members in Chiapas.

“I like to pick cherries,” Bacquez said. “This, especially, is the best time of year to make a little more money. And the job is kind of easy. Picking apples is harder.”

In the 10 years Bacquez has come to the Northwest, he said he’s never seen anyone but migrant workers in the orchards.

“That’s what I always ask myself, ‘Why do they say we are stealing jobs when they don’t want to do this kind of job?’ ” he said. In Mexico, “I didn’t have a chance. That’s the reason I had to come here.”

But he fears changes in immigration law may prevent him from returning, making this summer the last with the Gutzwilers.

Tariff entanglements

Sandison, the state ag director, met in Wenatchee on July 3 with U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., to discuss the potential damage of a second round of tariffs by China in response to tariffs placed on aluminum and steel by President Donald Trump. The new Chinese tariffs came three days later.

“That really had a negative effect on the growers,” he said. “It’s the producers, the growers, who in the end get hurt.”

China already had a 10 percent tariff on imports of U.S. cherries before the trade war kicked off. It added a 13 percent value-added tax this spring, then another 15 percent tariff, and later another 25 percent in response to the moves by Trump.

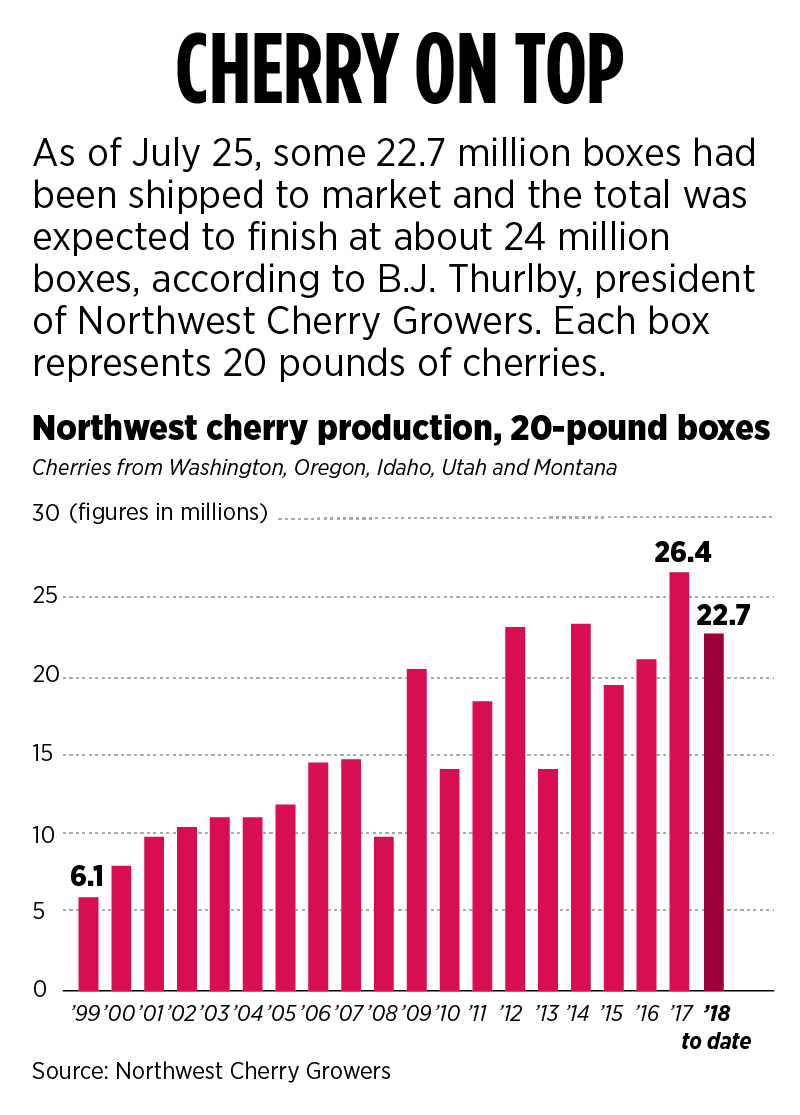

B.J. Thurlby is the president of Northwest Cherry Growers, which gets paid by producers to market the cherries to major retailers in the U.S. and abroad. He said the organization got its first cherries into China in 2002 and started direct flights to Shanghai in 2006.

“It took a few years to get it going. But it’s really taken off,” Thurlby said. “That’s because the middle class in China has really taken off.”

Last year, the trade organization that represents producers in Washington, Oregon, Montana, Idaho and Utah shipped 3 million boxes of cherries to China. This year that dropped to about 1.4 million boxes.

“It feels like we have been thrown under the bus four separate times since May,” Thurlby said.

The Chinese government eventually lowered the overall tariff to 50 percent, but then forced its importers to pay the tariff up front. In turn, the Chinese importers required the American exporters to lower prices to cover the 50 percent tariff, Thurlby said.

That means cherry growers eventually will get about half what they would have made last year.

“We just know the returns are going to be a bit lower,” Thurlby said. “But the prices this year have been pretty good. The domestic consumer has really taken to our fruit this year and we are grateful for it.”

Hot weather on the East Coast has helped farmers in Washington, he said. Thurlby explained that the association researches other items that American consumers purchase when they buy cherries. Some of the top items were hamburgers and buns.

“Cherries are the type of item they buy for a picnic or barbecue,” he said. “The consumer is getting a great year. They have great prices and great fruit.”

Life of riches

Norm Gutzwiler, 71, rises each day before the sun illuminates the Wenatchee Valley.

He walks his black Lab, Max, along the Columbia River before he heads to the orchard to carry on a family legacy that his grandparents started in 1902.

“It’s almost my second love,” Gutzwiler said of his cherries. “I’ve got my wife. I’ve got my hunting and fishing, and then I’ve got my orchard. It’s been a great way to raise our family.”

Gutzwiler, who along with Jake and Michelle farms a total of about 75 acres of cherries, began taking out the Bing trees a few years ago and replacing them with Skeenas and Sweethearts, which are both later-maturing varieties.

“We like to leave them on the tree until they reach full maturity,” he said. “We don’t get excited about getting them off the tree like earlier people. We try to give the consumer that last great taste of cherries before they go to apples and pears.”

Unlike apples, which can be preserved in cold storage and sold all year long, cherry growers must race to pick, process and place them on the shelf, where they only last about a week before they go soft.

“It’s such a sweet, delicate product,” he said.

But to start from scratch or to replace an orchard, the farmer must shell out about $40,000 an acre, said Gutzwiler, who earlier retired from his other job as a horticulturist.

“In the fourth year, you get a small amount of cherries to pay some of the debt back,” he said. “By the seventh year, you are hoping the markets are good.”

Farmers enjoyed a bumper crop in 2017. The conditions produced lots of cherries but the market was weak.

“Last year was probably my most disappointed year I’ve ever had,” Gutzwiler said. “A lot of people went out of business last year. A lot of us just flat lost money. We did not get the money back that we put into growing the crop.”

In 2017, some farmers received as little as 25 cents per pound. Earlier this year, the price had rebounded to about $1.25 per pound, he said.

“I can deal with Mother Nature. It’s something I can’t control,” Gutzwiler said. “But when it’s a market that we as an industry can control, that’s disappointing. We should be able to move that crop and get a return back to the grower.”

Michelle Gutzwiler said she was rooting through some of the items that Norm Gutzwiler “forgot” to move out when he sold the house to the next generation. In the corner, she found some of his old books.

“We found the cherry returns for 1976 and 1977. They got the same price then as it is now,” she said. “We’d be rolling in dough if we just made minimum wage.”

Despite the weak market last year and trade war this year, Norm Gutzwiler said he’ll continue to follow his family legacy.

“It’s the life that we’ve chosen. You either enjoy it or you don’t,” he said. “I enjoy being outside. I enjoy watching the trees and the fruit. I enjoy my family and my neighbors. I’m very fortunate.”