If Tom Foley could lose in 1994, can Cathy McMorris Rodgers be beat in 2018?

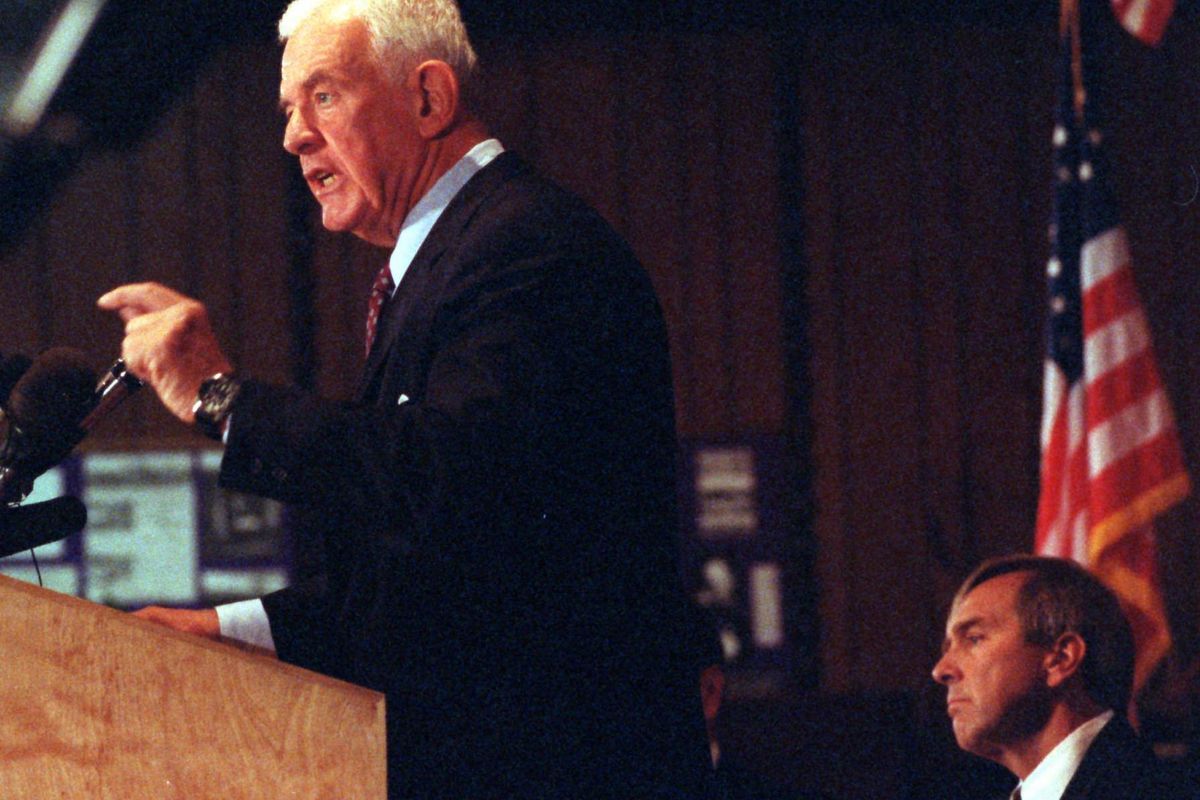

Tom Foley gets some tips from Ron Racek as Foley prepares to shoot Racek’s 45/70 buffalo gun at the Spokane Valley Rifle and Pistol Range outside Mica on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 1994. Foley met with club members in an attempt to counter negative NRA ads. (Sandra Bancroft-Billings / SR)

There was talk of a political wave as the midterm elections approached, generated by unhappy voters and eager political activists.

Some were unhappy about federal efforts to change the health care system, others about gun control legislation.

There were hints of scandal surrounding the new president, who had given his party control of both the White House and Congress for the first time in years. A relatively new news medium was hammering them 24/7.

The party of a new president usually loses seats in his first midterm election, but there was skepticism the losses would be so great as to cost his party the House of Representatives or dislodge some of its most powerful leaders.

But the opposition party was energized, with serious and well-funded candidates in districts they had previously shrugged off.

When the wave hit, it hit hardest in Washington, turning Congress – and the nation’s political landscape – upside down.

This is obviously not a description of the 2018 mid-term election, almost seven months away. It’s a Reader’s Digest description of the the 1994 midterm election, which Democrats – who went from in control to out – hope will be something of a mirror image of this year.

There will be plenty of references to a wave election in the coming months, but it’s important to remember: While the similarities with 1994 are interesting, both in the nation and in Eastern Washington’s 5th Congressional District, there are also differences that will play out between now and Nov. 6.

Right person, right place?

A basic law in politics says that anyone can be beaten by the right opponent in the right year with the right campaign.

Republicans proved that in Eastern Washington in 1994, when political newcomer George Nethercutt beat Tom Foley, the sitting speaker of the House.

Democrats are hoping they can prove it again, in the same venue. This time a political veteran, former state Senate Majority Leader Lisa Brown, is running against U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, who as House Republican Conference chairwoman is the fourth-ranking member of GOP hierarchy.

Much like 2018, 1994 was a mid-term election for a first-term president who won the White House without capturing a majority of the popular vote. Bill Clinton, who won a three-way race with George H.W. Bush and Ross Perot two years earlier, tried and failed to overhaul the nation’s health care system, had signed the North American Free Trade Agreement, implemented “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” for the military and was under investigation for the Whitewater allegations.

Donald Trump, like Clinton, won the Electoral College vote but did not win a majority of the popular vote.

In 1994, Foley was finishing his 30th year in Congress and had never lost an election. In the previous decade, he had beaten Republican opponents by at least 10 percentage points, and in one case, by 50 points. His opponents were generally inexperienced, underfunded and considered tokens even by leaders of their own party.

The Democrats had been in the majority in the House since 1954, having even weathered the Reagan wave of 1980 which flipped the Senate to Republican. After the 1992 election, they held an 82-seat majority and eight of nine seats in Washington.

McMorris Rodgers is in her 14th year in Congress after serving 10 in the Legislature, and she, too, has never lost a race. She never had a close contest for her northeastern Washington state House seat, and the closest any congressional opponent came was in 2006, when Peter Goldmark got 44 percent of the vote to her 56 percent. In the past 10 years, McMorris Rodgers has been able to outraise and outspend her opponents – also generally inexperienced and not well-known – by at least 5-to-1, and in one case, 100-to-1.

Nethercutt represented a different kind of opponent for Foley. He was an adoption lawyer with ties to popular organizations like the Vanessa Behan Crisis Nursery. He was a new candidate, but not a political novice, having been chairman of the Spokane County Republican Party and active in the George H.W. Bush presidential campaigns. He’d also been an aide to U.S. Sen. Ted Stevens, of Alaska, something that the campaign didn’t shy away from but also didn’t tout in running on a platform of change against the establishment.

Brown is arguably the toughest opponent McMorris Rodgers has faced. First elected to the Legislature in 1992 – she and McMorris Rodgers served together in the House for two years – she beat a popular Republican incumbent for a Senate seat in 1996 in a bruising race in Spokane’s predominantly Democratic 3rd District. She rose in the Senate to serve as Ways and Means chairwoman and later majority leader before retiring. Shortly after leaving the Legislature, she was named chancellor of Washington State University-Spokane, where the new medical school she had helped push through the Legislature was being established.

Right time?

Some issues of 2018 might mirror those of 1994, at least at the first glance at the looking glass.

Clinton and congressional Democrats tried, and failed, to pass major health care reform after running on it in 1992. Trump and congressional Republicans tried, and mostly failed, to repeal and replace Obamacare, a much more comprehensive reform, after running against it in 2016.

Clinton did sign NAFTA, which was popular in some parts of trade-dependent Washington but not with a core Democratic constituency, organized labor. Trump has called NAFTA the worst trade deal in history, canceled the Trans-Pacific Partnership and called for tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, which gets support from some labor groups but not from a key Republican constituency, farmers, whose commodities face reciprocal tariffs in China.

Faced with questions of what to do about homosexuals serving in the military – at the time it meant a discharge – Clinton developed the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, allowing gay people to serve as long as they weren’t open about their sexual orientation. It was controversial with the military and with people it was designed to protect, and eventually overturned by the courts and Congress during a later administration, allowing military personnel to serve regardless of their sexual orientation.

Trump signed an executive order to ban transgender individuals from serving in the military, which was blocked by the courts, and recently issued a second order. It’s also controversial, with military officials telling Congress they know of no problems with transgender individuals and unit cohesion – a key element in a landmark court ruling against Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

Clinton also wanted a ban on semi-automatic, military-style rifles, commonly called assault weapons. Congressional Democrats were leery of the ban, and Foley reportedly tried to talk the president out of it, saying it would cost some members their seats. Clinton continued to push, and the House voted to include the ban in a major crime bill. Foley refused to comment on the ban until a mentally unstable former airman with an assault rifle shot up the hospital at Fairchild Air Force Base, killing five and wounding 23. Foley said he supported the ban and voted for the crime bill when it passed a few weeks later.

The National Rifle Association, which had been a consistent supporter of Foley’s, threw its considerable weight against him. Nethercutt, vying for that support with three other GOP challengers, at one point said he’d draw a high line for the Second Amendment – “at nuclear weapons.” He later said he was not serious about that comment. After he won the primary, the NRA was squarely behind him.

The 1994 assault weapon ban expired in 2004, and those weapons are once again a key political issue. Supporters of new restrictions on those weapons have held major demonstrations around the country, since the Feb. 14 mass shooting at a Parkland, Florida, high school. Along with their marches, they are registering participants to vote and promising to keep up the pressure.

Are gun issues a deciding factor?

A recent poll of 5th District voters by Elway Research Inc. indicates nearly two-thirds support raising the age to purchase a semi-automatic rifle to 21, from the current age limit of 18. McMorris Rodgers opposes such a change; Brown supports it.

The poll, commissioned by The Spokesman-Review, KHQ-TV, the Walla Walla-Union Bulletin, Spokane Public Radio and the Lewiston Tribune, shows the level of support varies between men and women and across all age groups and levels of education. It gets a majority from self-identified Democrats and independents, and only falls below 50 percent among self-identified Republicans.

Although that would seem to help the challenger, that’s not a sure thing. In 1994, The Spokesman-Review and KHQ-TV surveyed 5th District voters less than two months before the election, after the assault weapon ban had passed. Nearly three out of four voters said they supported it.

But that didn’t help Foley, because in 1994, banning assault weapons became a key issue for many who opposed it, but was just part of a mix of issues for those who supported it. Nethercutt even had a member of his campaign committee who supported the ban after seeing the carnage such a rifle caused at Fairchild.

This year, it’s not yet clear if the people who march or become politically active for stricter gun control will base their vote primarily on that issue.

Where mirror gets cloudy

History doesn’t repeat itself, and there are key aspects of the 1994 election that haven’t surfaced.

Nethercutt and other Republican challengers signed on to the Contract with America, a series of promises to consider major changes if they took control of Congress, which included constitutional amendments on term limits, a balanced federal budget and a line-item veto.

It was the brainchild of former Rep. Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., who would later become speaker, and other GOP leaders. Democrats dismissed it as a gimmick, calling it a Contract ON America, but the issues had been tested with the public and shown to be winners.

Washington state voters had enacted term limits for members of Congress through an initiative in 1992, something Foley and many legal scholars argued couldn’t be done without an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. He joined the lawsuit to challenge the initiative. Nethercutt said Foley was “suing the voters” and vowed he’d never do such a thing.

Some analysts have argued it was the lawsuit over the term limits that cost Foley the election. But that ignores the fact that I-573 failed in the 5th District. The Supreme Court later ruled congressional term limits do, in fact, require a constitutional amendment and the Republican-controlled House never mustered the votes to pass it. When Nethercutt ran for re-election to a fourth term, he won.

In 2018, there is no one yet to step into the role Gingrich played, and no coherent nationwide strategy for Democrats other than solid opposition to Trump. But the Contract with America didn’t even surface until September of that year. In spring 1994, few people were talking about a wave election.

H. Stuart Elway, the pollster for the news organizations’ recent poll, said when he tested the 5th District race in April 1994 as part of a statewide poll, Foley was ahead of Nethercutt by 4 percentage points.

But it’s hard to compare that to last week’s poll, which shows a six-point spread in the current race, with McMorris Rodgers at 44 percent and Brown at 38 percent. The 1994 poll was a smaller sample with a much larger margin of error.

A later poll of Eastern Washington voters during the 1994 campaign pointed to what may have been the biggest factor in Foley’s defeat. Asked for the most important issue to them in voting for Congress, one out of four answered with a single word: Change.

Clinton was elected in 1992 on a platform of change, and Democrats captured eight of Washington’s nine U.S. House seats in that election. By 1994, voters still wanted change, but a different kind, and seven of nine Democrats, including Foley and a one-term congressman from Central Washington named Jay Inslee, were ousted.

“We had the farthest swing of any state in the country,” Elway said

Dissatisfaction was fanned into anger by conservative talk radio and they voted in large numbers. Some traditional Democratic voting blocs, like organized labor, dropped off.

The contract allowed Republicans to nationalize the election, and that put 5th District voters in a special position: They could send an even greater message about change by voting out the speaker of the House.

Voters who supported Trump in 2016 also said they wanted change. If it’s not the kind of change they expected, his fellow Republicans could pay the price in November. But Elway isn’t convinced yet that a “blue wave” will swamp the Republican districts, even though Democrats seem to hold an advantage among voters in a recent statewide poll.

Washington’s 10 congressional districts are divided currently into six that are relatively safe for Democrats and four relatively safe for Republicans. Dividing the responses in the statewide poll between the six Democratic and the four Republican districts, the incumbents of each party hold the edge among voters when matched against a challenger from the other party.

Democrats seem to be more energized about the election, and Republicans incumbents have a smaller lead in their districts.

“If the numbers were reversed, you’d probably say ‘Holy smokes! Red wave coming,’ ” Elway said. “But it’s hard to do (1994) in reverse.”

Jim Camden, The Spokesman-Review’s Olympia bureau reporter, has covered politics for the paper since 1984, including the 1994 congressional race.