Vietnam vets remember things that sometimes get missed

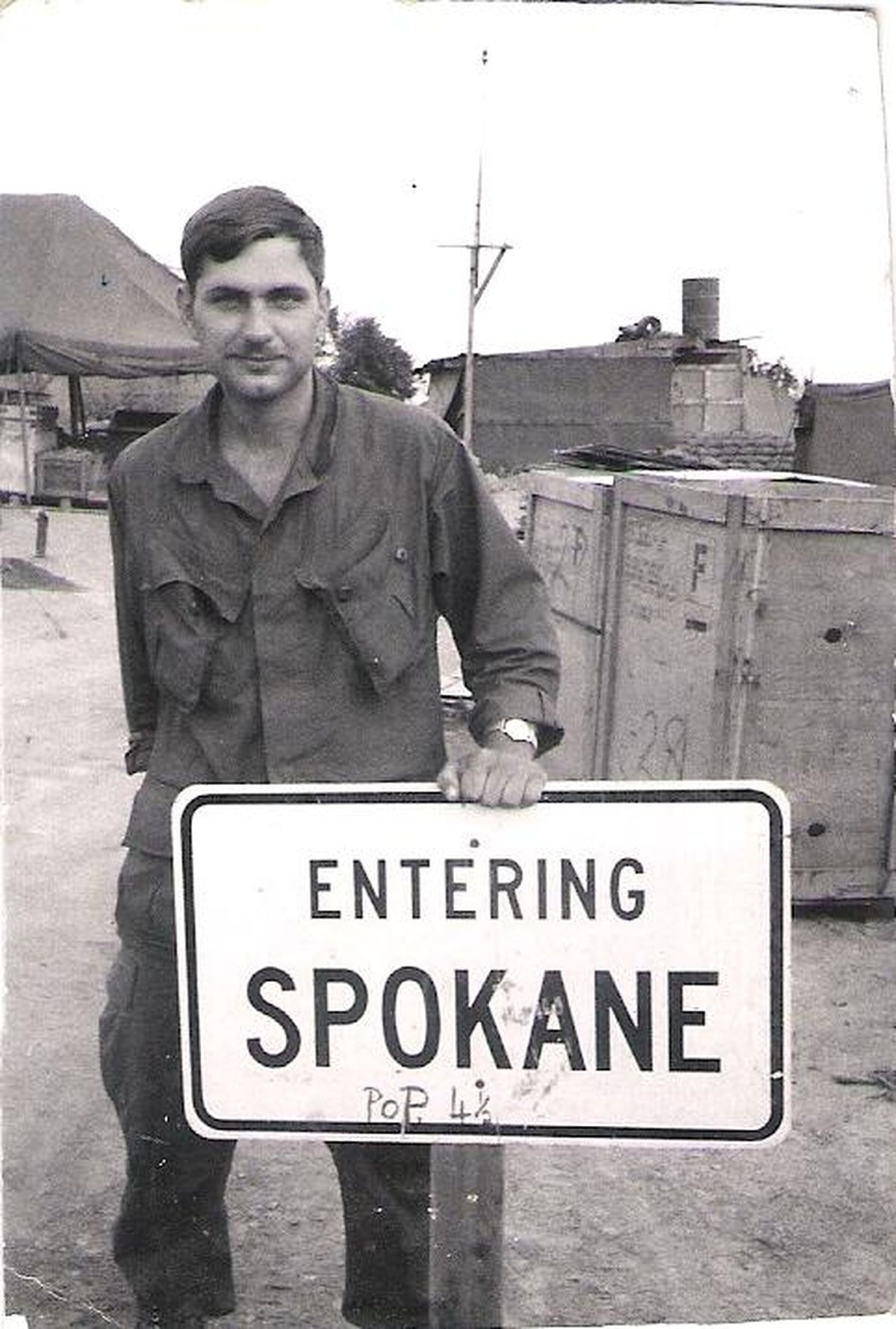

Larry Plager, a young Marine from Spokane, is seen in this snapshot from 1969 taken in Vietnam. He was part of a group of new Marines from the state of Washington that enlisted together. (PHOTO COURTESY OF LARRY PLAGER / PHOTO COURTESY OF LARRY PLAGER)

We’re all familiar with the expression.

“You had to be there.”

In one specific use, it’s something veterans of the war in Vietnam sometimes say. They say it when feeling frustrated in their attempts to convey the sights, sounds and heartache of that cataclysmic period in American history.

Maybe that’s because not every aspect of each soldier’s experience can be reflected in even the most well-intentioned documentaries or retrospective journalism.

So what has been left out?

Medical Lake’s Larry Plager spent 1969 in Vietnam as a combat Marine. He’s 67 now. The 1968 graduate of Ferris High School said there’s at least one war reality he has not seen depicted.

It’s this. Battles and skirmishes would begin with sudden ferocity. But in between engagements with the enemy there sometimes would be long stretches when seemingly nothing happened.

Just heat, rain, mud and bugs.

And it’s those prolonged doldrums that can be hard to capture, Plager said. For the grunt, a term he used, the absence of a firefight did not equate to true rest and relaxation. You were always on edge. You were constantly aware that, at any moment, all hell could break loose.

It might have seemed as if it was down time, but it did not feel like it.

Mike Bauer, a Ritzville area farmer, went over in the summer of 1971. He was an artillery officer. He’s 70 now.

Once while he was watching a rice farmer, he decided he would like to talk agriculture with the man, one grain farmer to another. So he got an interpreter to facilitate a conversation.

The farmer told Bauer he did not care about politics. He was just trying to make a better life for his family.

Bauer said he realizes, for all he knows, that same farmer could have been shooting at him the next day. Still, their brief encounter at the rice paddy was a moment unlike anything he has seen in Vietnam documentaries.

Mack Stanhope, 77, who lives up in Marcus, Washington, was in the Air Force and spent much of his time in Vietnam, 1965-66, at Da Nang Air Base. He doesn’t worry about what gets left out of retrospective accounts. He’s just pleased when not everyone in the U.S. military of that era is portrayed as drug crazed savages. “We weren’t.”

So what else has been left out of documentaries on Vietnam?

“The reaction of my patriotic mother,” said Bill Sawatzki, a longtime Liberty Lake resident now retired in San Diego. “She turned against the Vietnam War when I was injured and hospitalized.”

Sawatzki, 71, got hit with shrapnel from a mortar round. “Good enough to get back to the world.”

David Valandra, who grew up in the Seattle area, enlisted in the Army and went to Vietnam late in 1966.

“You don’t really get a sense from television of just how loud everything is in combat.”

A longtime Spokane resident who now lives near Phoenix, he is 70.

But he still remembers with piercing clarity the smell of burning Vietnamese vegetation, and the haunting aroma of weapons fire.

He said one thing that’s hard to capture in documentaries is the mind-blowing disorientation of coming home. “One day you’re out in the bush and then the next day you’re on a plane. There was no decompression time at all.”

Alex Renner, 70, enlisted in the Marines and went to Vietnam in 1966, not long after graduating from North Central High School.

A buddy convinced him being in uniform would help them pick up girls. Looking back, he acknowledges they were not really seeing the big picture.

Renner guessed it’s hard for filmmakers to convey the feeling that results from a prolonged lack of sleep. (Rocket attacks in the middle of the night or the threat of same tend to prevent quality rest.)

The only other time he has been that tired was when he came home and was working at a sawmill during the day and staying up all night courting a young woman. “But that was a different kind of tired. I was in love.”

Peter Yocom, 73, who has lived in Spokane since 1991, was in Pennsylvania when he entered military service. He went to Vietnam shortly after the Tet Offensive in early 1968. He was an Air Force intelligence officer and spent much of his time interrogating prisoners.

He said it would be difficult for any television treatment of the war to adequately reflect the confusion, corruption and chaos he witnessed. “No purpose. No direction. Nobody talked to each other. It was an enormous waste.”

Cheney’s John Barber, 69, who grew up in the Baltimore area, joined the Army in 1966 to pre-empt being drafted, which he viewed as a certainty. He went overseas in the fall of 1967 as part of an assault helicopter company.

He thinks one big missing piece in televised presentations about the war is a close look at what happened to the pro-American segment of the Vietnamese population after U.S forces pulled out prior to the end of hostilities in 1975.

Terry Strong, 70, was drafted after graduating from Shadle Park High School in 1965.

He served in the infantry while in Vietnam and saw his share of the horrors of war up close.

Still, his perspective on his experience isn’t something you are apt to see in documentaries.

“If I hadn’t have been drafted, I’d have wound up dead.”

But illegal street rod drag-racing didn’t get him and neither did the Viet Cong.

Johnny Erp, a 68-year-old New Yorker who now lives in Spokane, did two tours in Vietnam, starting in 1967.

He saw a change in the mindset of the American troops that can be hard to portray on a TV screen.

“Once you realize we’re not in it to win, everything’s different. We were just young guys. We were not educated, but we were not stupid. You had to ask: Why are we still here? Why are we still dying?”

Erp said he started out thinking he was fighting to save the world from Communism.

In the end, he was just fighting for the guy crouching next to him.