Visit to Thailand for sisters is poignant journey home

“I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word.”

Martin Luther King Jr.

This is the story of a priest, an airman and a family in Spokane.

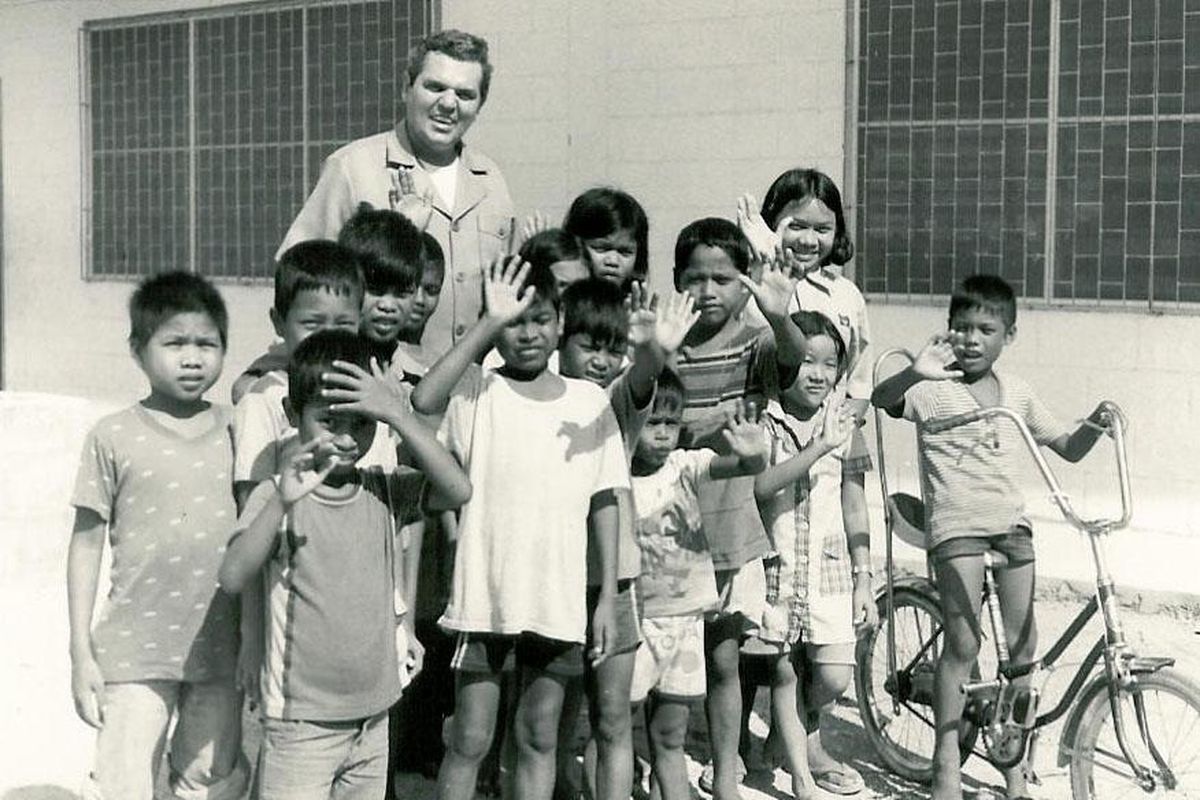

Among military uniforms the man in a white ankle-length cassock was a standout, easy to spot when he came on base to offer Mass and counseling. The big American missionary seemed even larger to the slightly built Thai people he helped in multiple poor villages before, during and after the Vietnam War in Southeast Asia.

Born during the Great Depression to an Irish family on the gritty south side of Chicago, the Rev. Ray Brennan, of the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer of the Roman Catholic Church, was entirely familiar with the need and hopelessness that arise from poverty. He was drawn to the Redemptorist order, founded to minister to the poor and unwanted. Following his ordination in the 1950s, he was assigned to Thailand and served there for the rest of his life. His mother wasn’t surprised and said that of her three children, Ray was the only one who liked rice.

Brennan spent his first 10 years in northeast Thailand not far from the Air Force base at Nakhon Phanom by the Mekong River. His was a well-known face on most military installations when he was reassigned to a small parish 400 miles southwest of Nakhon Phanom on the Gulf of Thailand. Pattaya was a rest and recreation site for servicemen and was widely known for its beautiful beaches and busy prostitutes.

By 1974, a wave of “war babies” was well underway, most biracial and rejected by Thai society. On the steps of Brennan’s parish church, a woman handed the priest her baby. The baby’s father had run away, and her new husband didn’t want it. Word spread that Brennan would take unwanted children, and more mothers approached him, including one from Rayong who hoped for better lives than she could provide for her four little girls.

Enter the airman.

U.S. Air Force Capt. Les Bruess was a staff officer on a one-year assignment to Nakhon Phanom. Usually accompanied by his wife, Mary, and three children, Bruess arrived solo to this station but stayed in close touch with family. He met Brennan and heard about the girls. The four sisters were housed temporarily in a bilingual home where they learned a few phrases in English, and some American customs, such as using a fork, sleeping in a bed, and sitting on a toilet.

Bruess phoned home for a command decision.

“My husband and I had talked about adopting a child, but the idea was ‘maybe someday’ and in the future,” said Mary Bruess. “He was away in Thailand and called to say he could adopt over there. He said, ‘Do you want two or four? I need your answer now.’ I said, ‘Yes, let’s go ahead.’ ”

Les Bruess completed the formidable paperwork, endured a thorough vetting, arranged for vaccinations, and adopted two of the girls, Ganya, 9, and Varee, 8. A second airman did the same for their sisters, Anchalee, 6, and Boonchu, 12, and took them to their new family in Texas. The two men agreed to keep the sisters in touch with each other.

Mary flew to Thailand to join her husband and meet Brennan, who pointed to a large empty field and said he wanted to build an orphanage on it. Les gave the girls clothes, toys, and a small transistor radio to entertain them, and the new adoptive parents brought their daughters to America.

While waiting in San Francisco for a connecting flight to hometown Omaha, Varee angrily pounded the little radio on the floor. She wailed it was no good because it wouldn’t speak Thai anymore.

Ganya and Varee were welcomed warmly by their excited new siblings, Anna Rae, 15, Scott, 14, and Alan, 10, who gave them his teddy bear. Brother Kenny lived off-site in a nursing home for cerebral palsy patients.

“Ganya held on to her Thai ways,” said Mary, “and kept her hair long, waist length. But Varee said she was going to be American, and cut hers short.” Mary said when the girls arrived they wore size 6X clothes, much smaller than other nine- and 10-year-olds.

Both girls added generous helpings of Tabasco sauce to meals to make them Thai-hot.

“We had a little bottle of Tabasco we hardly ever used,” recalled Scott Bruess. “But they wanted a lot of spicy food, and then we were buying the jumbo size.” Rice consumption also increased. When the family prepared food together, Varee wore sunglasses as she chopped onions.

“I only had brothers up to then, so I was very excited to have sisters,” said Anna Rae Goetz, the Bruesses’ oldest child. “They fit in really well, and it was fun trying to teach them the language and the way of life. Varee watched me a lot and tried to emulate me, so I probably spent more time with her. She was quiet and withdrawn at times, trying to take it all in about the American way.”

After a brief stay in Omaha, the military family packed up for a two-year tour in Japan. All the children were enrolled in English-speaking schools there, made friends, and adapted quickly to Japanese culture. Ganya and Varee had not been in school before, and started at the third grade level. Within six months the sisters had a fair grip on the English language.

“I heard them arguing one day, and realized they were fighting in English instead of Thai,” said Les. “Right then we knew they had arrived.”

Home in Spokane

The tour passed quickly, and Les decided his final station prior to retirement was Fairchild Air Force Base. The Bruess crew found a South Hill house near schools, and Kenny moved to a care facility in Medical Lake. Freshly civilian, Les used his GI Bill benefit at Eastern Washington University while Mary settled their brood in Lincoln Heights Elementary School, Libby Junior High and Ferris High School.

The transition wasn’t all smooth. The South Hill schools were not as diverse as those on military bases. Ginger-haired and blue-eyed Alan Bruess was close in age to Ganya, and both rode the same school bus. A boy bullied Ganya and pulled her dark hair. She warned him that her brother Alan was on board, and the boy jeered that they couldn’t be brother and sister. Alan decked him.

That evening the bully, now sporting a black eye, and his mother came to the Bruess house. She demanded to know why Alan had hit her son. When Alan described what had happened, the mother grabbed her boy by the ear and dragged him home.

Mary told of a later incident during Ganya’s high school years. A boy asked Ganya to a dance, but called later to say his mother objected. He couldn’t take her to the dance because she wasn’t white. Other kids made remarks about her eyes “looking different.”

As the years ticked by, Les worked in environmental engineering, Mary managed offices at Spokane Community College and St. Peter’s Church, the five kids attended colleges and began families of their own. Kenny died in 1989. Les retired a second time, and Mary her first. Both became deeply involved in work for their church and local charities including Crosswalk, the food bank, and Bare Necessities – a group that provides pajamas for area foster children. For fun they cheered for the Seahawks with kindred fans in a booster club.

As adults, the Bruess siblings also thrived. Anna Rae is a legal secretary, Scott keeps the books for a resort near Sun Valley, Ganya Moen works in childhood development, Varee Curl is a dental assistant, and Alan an entrepreneur. In Texas, Anchalee Miller is a nurse, and Boonchu Garrett works in hospital food service.

Then Varee started a ball rolling. Straight to Thailand.

“I wanted to see where I was born,” Varee said. She left Spokane in August 2016 to spend two weeks in Southeast Asia. Bangkok with its 14 million people was overwhelming, so she drove south to her hometown of Rayong. “I wasn’t intent to find my Thai family. I just wanted to see the village and countryside, the real Thailand.” They drove by rice paddies and plantations of pineapple, bananas and jackfruit.

Rayong had grown far beyond her memory of a seaside village, but memories rushed up to her at the beach. “It was the best thing I did in Rayong,” she said. “All these years I had some memories inside of me about my Thai mother and brother – but as time passed you forget. Now I stood on the place where I played with my sisters and I remembered. I picked up some little seashells and brought them home with me.”

Varee’s travel experience inspired Ganya to research and organize a similar trip to Thailand for 12 days in July 2017. The party included sisters Boonchu and Anchalee from Texas, Varee’s daughter Amanda Slemp, Ganya and husband Todd.

Ganya’s itinerary also highlighted Rayong, but hers was a mission to find Thai family and neighbors.

She recalled living with her mother and grandmother in Rayong. “We would go to the market to sell beef and pork. I would assist by wrapping the meat in banana leaves for the customer. If they gave me baht (Thai money), I would put it in the drawer.”

The group explored the town for the old neighborhood the sisters remembered, and from a doorway a woman called out Ganya’s name. Through translation by their bilingual taxi driver the woman told Ganya they had been childhood friends. She had known the sisters’ older brother and birth mom, and told them she had died in 1989. “Then she pointed to our youngest sister, Anchalee, and said she looked just like our mother,” Ganya said.

“It was an emotional, beautiful moment. Here we were, halfway around the world to hear that,” she said.

The travelers also visited the Pattaya City orphanage compound Brennan had begun to build the year after the little girls left Thailand. “They greeted us with open arms,” Anchalee said. “They said, ‘Welcome home!’ ”

Orphanage is born

In the 29 years following the girls’ departure, the priest continued to visit military installations. He enlisted financial and physical help from GIs to construct the first building on land donated by the local Catholic diocese. Brennan established a foundation through which he could support the orphanage. The diocese directed nuns to staff it, and to teach the children.

Eventually the project included schools for blind, deaf, and disabled children, a nursery building for infants, separate housing for older boys and girls, a big kitchen/cafeteria, and meeting areas. Children receive solid education continuing to a bachelor degree at no expense to themselves. In recent years, the orphanage has established orchards, rice paddies and vegetable gardens to supplement the kids’ nutritional needs. The compound now supports 850 children who consume 60 tons of rice each year.

“My goal is not to change the world,” the missionary once said, “but to teach the children enough to hold their heads high, to earn their own rice and to have a good human life.”

The Bruess family corresponded with Brennan, sending school pictures of all their children, and eventually news of weddings and babies.

Brennan died in 2003 from heart failure. His funeral was the largest ever seen in Pattaya. The king and queen of Thailand sent a packet of royal soil which was to be buried with the priest, the highest honor a person can receive in Thailand.

But the priest’s legacy continues, instilling self-respect and independence in new generations of Thai children. The Bruesses still marvel that they had some early influence on Brennan’s vision.

Their Thai-born daughters plan a four-sister trip to Thailand in 2018. Varee and Ganya are relearning Thai, and Anchalee intends to bring her nursing skills to Brennan’s orphanage. All of them want to connect in person with their Thai brother. All of them love their American families for giving them opportunities they might never have had in 1974 Thailand.

Said Ganya: “I want to be a giver now more than I have been, and share my happiness. My heart is full.”