Getting There: City floats plan to phase parking lots out of downtown

Parking lots are the worst. Wide, paved expanses that add nothing to the beauty of downtown Spokane.

Yet they also serve a basic function in today’s world. About 80 percent of commuters drive alone to work, and they have to store their cars somewhere.

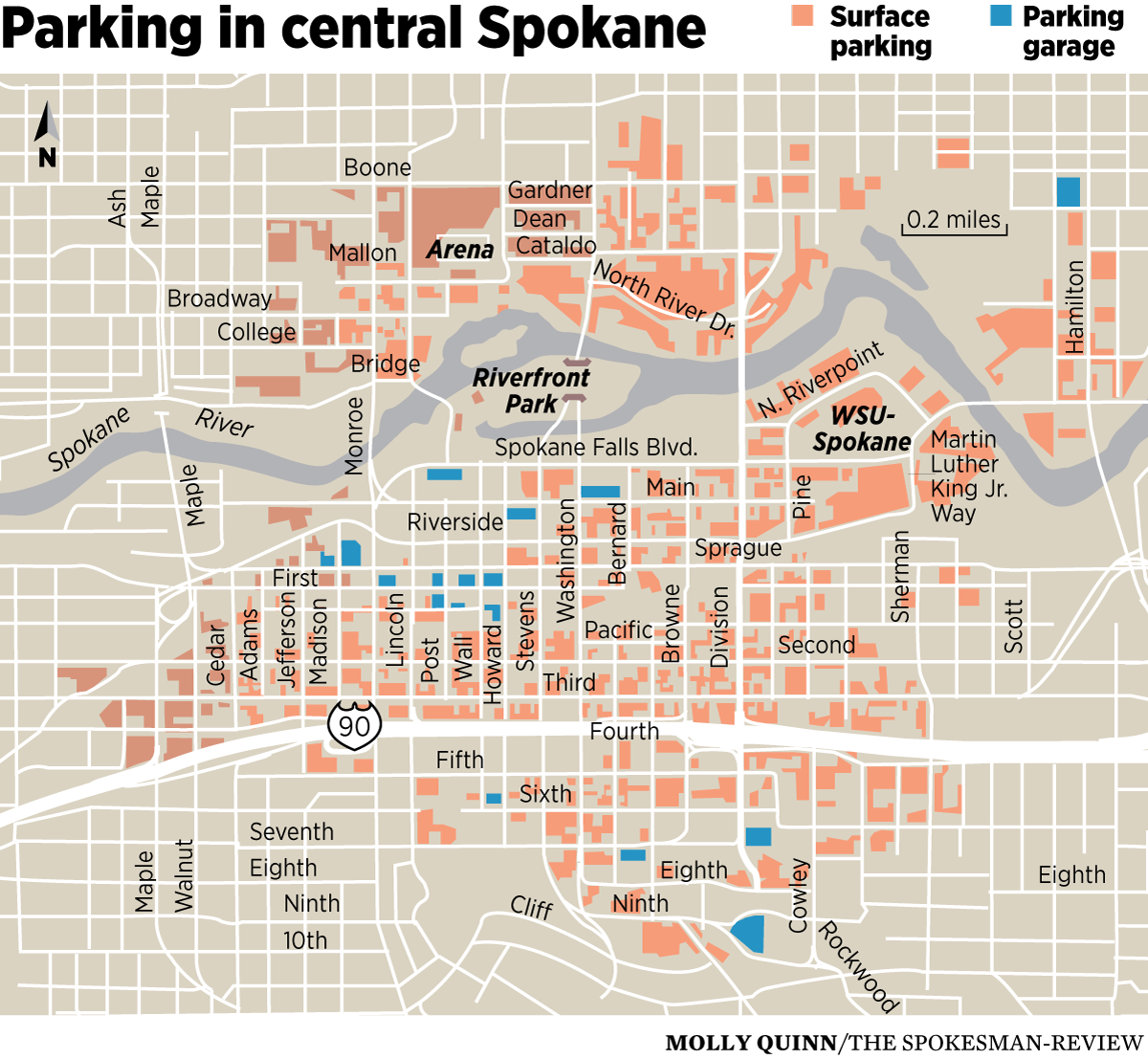

In downtown Spokane, they have plenty of options: 12,658 options, in fact. That’s how many parking spaces there are in the city core, about 80 percent of which is off-street parking in privately owned lots and garages.

But with growing numbers of planners and urban thinkers arguing that parking lots have hollowed the cores of American cities, the era of the surface parking lot may be coming to an end. And an accidental idea from City Hall may hasten their demise, at least in the state’s midsized cities.

The idea is simple enough: offer developers a 10-year break from taxes on any project they build on what is now a surface parking lot. It could be a residential tower or an office building. It could even be a parking garage. Anything.

“If you build something other than surface parking lot, you get a tax abatement,” said Andrew Rolwes, the public policy and parking manager for Downtown Spokane Partnership who is credited with coming up with the proposal, which must be approved by the state Legislature. “Nothing like that exists on the books.”

Philadelphia instituted something like it in 2000, waiving taxes on improvements to residential and commercial properties, which is credited, in part, for reducing the number of surface lots in the City of Brotherly Love.

Spokane may be the test case for Rowles’ and Spokane City Council President Ben Stuckart’s unique idea.

Makes sense, since Stuckart said the idea came after he gave a presentation at Spokane City Hall about the city’s multifamily tax exemption, a program that waives some taxes for developers of apartments and similar buildings that provide denser housing.

Stuckart already had been mulling how to spur development on parking lots, but was leaning toward taxing the land for its “highest and best use.” Hartford, Connecticut, is trying this form of development compulsion, but has faced stiff opposition from parking lot owners who say creating a special taxing district to force them to develop or sell their downtown properties is unfair.

After Stuckart’s presentation, Rolwes texted him: “Why don’t we do this for parking?”

With that, the idea flipped on its head. Instead of increasing taxes on parking lot owners, the plan will give tax breaks to developers who turn parking lots into something, anything, other than a plane of pavement. Under its current, draft version, it only applies to cities with populations between 150,000 and 250,000. And it’s aimed at redeveloping not just parking lots, but any vacant land.

Still, it’s clear what Stuckart wants the proposed legislation to do.

“We don’t want surface parking lots in our downtown,” Stuckart said. “There’s 74 of them. They don’t actually serve a good function.”

He’s right. A vestige of city planning completely centered on the automobile, parking lots create their own vicious cycle. As the automobile became the dominant form of transportation and more and more people drove, they gobbled up parking in downtown areas. Developers demolished buildings to provide for the demand. As more lots went up, more people drove, creating more demand, leading to more parking lots.

It doesn’t take a mathematician to see the disastrous end of that equation.

In recent years, urbanists and planners have pushed back against parking lot mania. Their working assumption: Surface parking lots are the scourge of downtown.

Like much of the modern transportation system, motorists enjoy the benefits of convenient parking without realizing the hidden costs and subsidies that support it. That’s tough to grasp, knowing that cars are immobile 95 percent of the time.

A study published in July by the Victoria Transport Policy Institute in British Columbia calculated the actual cost of parking at $2,400 a year per car, considering cost of land, construction, maintenance and operations. But most Americans spend $85 annually on parking. If we paid the actual cost of parking, Americans would drive about 16 percent less, or about 500 billion fewer miles a year, according to a projection by the study’s author.

Rolwes says parking “provides critical access to downtown,” but said most people would prefer parking in “structured, covered and secure parking,” otherwise known as parking garages.

But those garages are expensive. A recent study by Carl Walker, a parking consultant firm, estimated that the median construction cost for a new parking structure is $19,700 per stall.

“Parking garages are economically challenging structures to build,” he said. “They don’t have the economic attributes that mixed-use office buildings have. Surface parking lots are more of a sure thing.”

That “sure thing” accounts for the need for a tax abatement, Rolwes said, while acknowledging that a number of parking garages are planned for the city’s core that don’t rely on this tax break. Notably, developers have proposed the Montvale Parking Garage on the west side of downtown, and two just north of the river, one connected to the Falls project on the YWCA site and one as part of the renovation of the Wonder Bread building.

For Stuckart, getting rid of surface lots is all about economic development and aesthetics. The “holes” in the city’s retail core are bad for business and take away from enjoying downtown, he said.

“A successful retail area does not have holes,” he said.

On a recent walk from River Park Square to the flourishing east end of Main, Stuckart was struck by the varying levels of development.

“You keep running into these lots that are empty,” he said.

On average, 58 percent of downtown parking spaces are taken. With nearly 300 acres of surface parking in the city core, that equates to a lot of empty paved space – about 6,000 empty parking spots worth.

Stuckart is hopeful that he and Rolwes’ idea will succeed. He said he recently went to Seattle with Mayor David Condon and met with a receptive Jonathan Diamond, who controls the international Diamond Parking empire headquartered in Seattle, which owns more than half of downtown Spokane’s lots.

Stuckart’s also talked to a handful of state legislators, including Spokane Democrats Sen. Andy Billig, Rep. Timm Ormsby and Rep. Marcus Riccelli, as well as Spokane-area Republicans, Sen. Mike Padden, Rep. Bob McCaslin Jr. and Rep. Mike Volz.

He’s already written the bill, and Riccelli took it to the state Department of Revenue for comments and edits. Ormsby told him to get a bill sponsor who sits on the state House Finance Committee, where it will begin its journey toward what Stuckart hopes is the governor’s desk.

“Frankly, I’ll fly wherever I need to. I want a sponsor before December,” he said, adding that it will be the sole item he lobbies for personally. “This will be the only thing I go to Olympia for.”

The proposal is part of the Greater Spokane Incorporated legislative agenda. Mark Richard, president of Downtown Spokane Partnership, and Rolwes said they’d lobby for it in Olympia.

The bill is far from assured. Its path is complex, and even if it does become law, it’s unclear if it will stoke development at all. Still, Stuckart has high hopes for what he says is a simple idea.

“Every Republican that I’ve briefed so far has been supportive. The Democrats I’ve briefed have been supportive. I haven’t met anybody yet that thinks this is a bad idea,” he said. “This is basic planning 101.”

Have a transportation question you want answered? Write nickd@spokesman.com.

Parking revenue brings projects

Speaking of parking, the Downtown Spokane Partnership released a new list of what parking meter revenue is doing for downtown.

In 2013, the Spokane City Council passed new rules to invest revenue from downtown parking meters into downtown projects. The idea is from Donald Shoup, a parking planning guru at UCLA who argues that parking policies in many cities are broken and have dire consequences for cities, the economy and the environment. He urges cities to charge fair market prices for parking and use the revenue to fund enhancements in parking districts.

Spokane, so far, has done the latter.

Since 2014, more than $1.5 million in paid parking fees has gone to a wide range of projects:

$150,000 for Lincoln Street gateway on Interstate 90 off-ramp

$235,000 for the Division Street Gateway

$410,000 for the Division I-90 off-ramp

$150,000 for I-90 landscaping and design work

$100,000 for Main Avenue parking reconfiguration and landscaping

$114,000 dedicated to four years of hanging flower baskets at Post, Main, Wall, Bernard and Brown, and Division I-90 gateway

$40,000 for holiday decorations

$6,000 toward local art on traffic signal boxes

$5,000 for bike racks

As for fair market pricing of parking, that’s a whole different issue. But city-owned, on-street parking costs $1.20 per hour. Privately-owned, off-street parking averages $2.12 an hour.

We don’t honk

A recent poll done by PEMCO Insurance found that 78 percent of drivers in Washington and Oregon say they rarely or never honk their horns. Laying on the horn is simply impolite, said 55 percent of respondents.

Despite such polite passivity, drivers here believe that honking is an effective way to get fellow commuters to get their mind in the game and off whatever is distracting them. About three-quarters of those surveyed agree that honking is the right way to tell other drivers to pay attention.

But the poll suggests that our politeness may come from our sensitivity.

Nearly half of drivers report being startled when other drivers honk, and a quarter of respondents say the gesture makes them feel bad. Another quarter says honking makes them mad.

Only 6 percent admit to letting other drivers know they’re mad, but PEMCO gave no word on how readily we use the finger.

State seeks volunteers for mileage tax pilot

The Washington state Transportation Commission still is seeking volunteers for a pilot project in which about 2,000 volunteers will pay a mock tax on the number of miles they drive on Washington state roads, rather than on the amount of gas they use.

Ara Swanson, spokeswoman for the commission, said her agency is about halfway through the recruitment process, and has volunteers signed up from every county in the state except for Ferry, Garfield and couple on the West Side.

They want more “to ensure representation across the state.”

“We definitely want rural drivers,” Swanson said. “We know there’s skepticism. It’s not policy yet. We’re doing this to see if it’s the right thing. It’s a great way for them to have their voices heard.”

The commission hopes to have all its volunteers before Thanksgiving, and they plan to start contacting invited participants early January. The pilot will get started in late January or early February.

For more information or if you’re interested in signing up, visit Waroadusagecharge.org.

Seltice Way gets paved

Paving of the north side of Seltice Way in Coeur d’Alene began this weekend, and is expected to be completed within a week.

Access to Seltice Way from Atlas Road will be closed during paving.

When complete in 2018, the $5.4 million project will include the final lift of asphalt on both sides of the roadway, a new, 12-foot-wide shared-use path on the north side of the road, bus shelters and landscaping within and around the roundabout at Atlas and Grand Mill Lane.

Napa closed for sewage tank work

Napa near East Sprague Avenue will be closed Monday and Tuesday due to work to construct a combined sewer overflow tank. Detours will be in place.

The work is part of a nearly $16 million project to construct two tanks, one at 200,000 gallons and another at 1.5 million gallons.

The intersection of Riverside Avenue and Magnolia Street will be closed until Wednesday.