Northeast Washington silicon smelter plans raise concerns

Axel and Theresa Hiesener bought their house in August. If a silicon smelter is built near Newport, they would be looking at a 150-foot-tall stack across the field from their house. They are pictured on Oct. 18, 2017. (Becky Kramer / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

NEWPORT, Wash. – Last year, a Canadian company announced plans to build a $325 million silicon smelter in northeast Washington.

State and local officials hailed the project as a big win for the economically depressed rural region.

About 150 people are expected to work at the smelter, making high-grade silicon for use in solar panels and computer chips. Average wages are projected in the $70,000 range.

The smelter qualified as a “project of statewide significance,” eligible for $300,000 in state assistance from the Washington Department of Commerce. HiTest Silicon’s officials anticipate opening in late 2019.

“Not only would it potentially provide jobs for us, it also has very good benefits for Washington as a whole,” said state Sen. Shelly Short, R-Addy.

The smelter aligns with Gov. Jay Inslee’s aspirations for making Washington a center for renewable energy, Short said. One of the smelter’s prospective customers is a Moses Lake refinery, REC Silicon, which makes polysilicon, the product ultimately used in solar panels.

As smelter details emerge, however, some local residents question whether the project is right for their area.

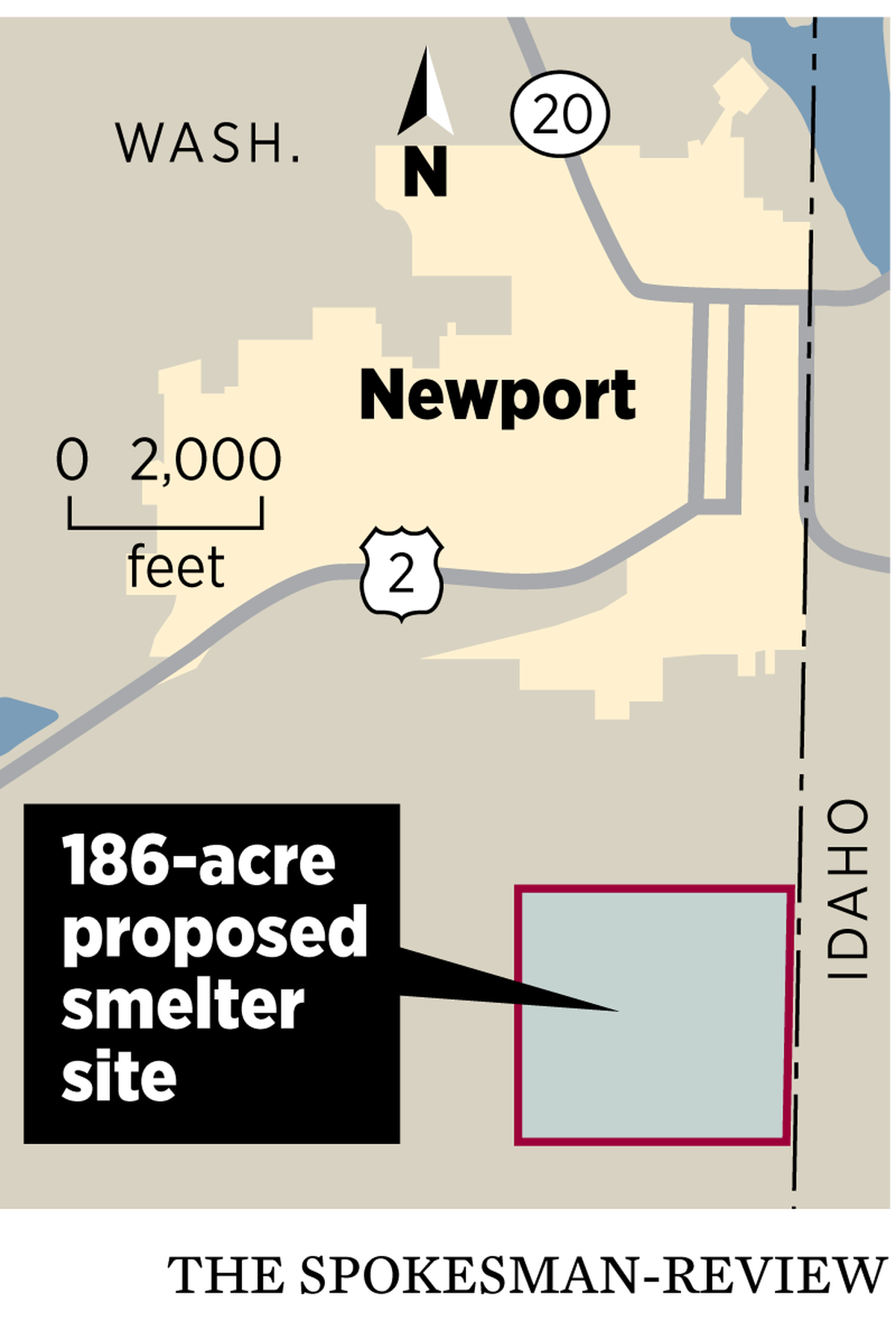

The 150-foot smelter stack will be visible to rural neighborhoods south of Newport, where HiTest Silicon – an Edmonton, Alberta, company – bought 186 acres in September.

With an expected output of 320,000 tons of carbon dioxide annually, the smelter would be Washington’s 15th-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, though company officials say the silicon’s eventual use in solar panels will offset the carbon emissions.

The Kalispel Tribe is concerned about other pollutants. A report from the company’s consultant said the stack will emit nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide – components in smog and acid rain.

All of this alarms Theresa and Axel Hiesener, who recently purchased a house in Solar Acres, a rural residential development south of Newport.

Mountain views attracted the former California residents to the property. They were shocked to find a flyer about the smelter on their screen door in early October, less than two months after they moved in.

“There is a place for heavy industry,” Axel Hiesener said. But he doesn’t think it should be so close to neighborhoods.

The smelter property’s boundary is about a a quarter-mile from the Hieseners’ house. Under Pend Oreille County’s zoning regulations, the smelter could be built on the site with a conditional use permit.

“This is our retirement home, our forever home,” Theresa Hiesener said. If the project is built, “we’ll see the stacks from our front door.”

Turning rocks into silicon

HiTest Silicon got its start in 2012, when several of the owners bought a high-quality silica deposit near Golden, British Columbia.

Silica is common in the Earth’s crust, but few deposits are pure enough to produce silicon metal, company President Jayson Tymko said.

“We acquired the property for different reasons, but once we realized the deposit’s purity and rarity, we changed course,” Tymko said.

HiTest hired a former Dow Corning Corp. executive with silicon smelting experience and started looking for a smelter location. The company needed cheap electricity and wood chips from nearby sawmills. Northeast Washington had both.

The Pend Oreille County Public Utilities District sold the company the 186-acre smelter site. If the smelter is built, HiTest would become the utility’s largest customer, buying an average of 105 megawatts of electricity. Much of the electricity would come from the utility’s Box Canyon Dam.

Producing silicon is energy-intensive. The silica is mixed with wood chips, coal and charcoal and heated in electric furnaces to temperatures of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

“We melt the rocks and turn them into silicon metal,” Tymko said. “That’s the simplest way to say it.”

During a chemical reaction, the oxygen bond in the silica breaks, leaving pure silicon. The released oxygen bonds with carbon from the wood chips, coal and charcoal, creating carbon dioxide.

“It’s a very natural process. No chemicals go into it,” Tymko said.

HiTest’s smelter would run continuously, producing about 60,000 metric tons of high-grade silicon per year. Silicon’s going price is about $3,200 per ton, Tymko said.

If market conditions remain favorable, HiTest would consider doubling the smelter’s production in the future, the consultant’s report said.

Emissions concerns

Aside from the carbon dioxide emissions, Tymko said, “relatively small” amounts of pollutants will come out of the smelter stack. That’s not a characterization the Kalispel Tribe agrees with.

“We are very concerned about the potential green washing of a significant polluter,” said Deane Osterman, the Kalispel Tribe’s executive director for natural resources.

The Kalispel Tribe has a 4,660-acre reservation bordering the Pend Oreille River. The tribe has applied to be a federal Class 1 airshed, the same designation given to wilderness areas and national parks.

The smelter’s projected emissions of smog- and acid-rain-causing pollutants are six to 18 times greater than the threshold requiring permits for new polluters in Class 1 airsheds, the consultant’s report said. Besides the Kalispel Tribe, a dozen Class 1 airsheds lie within a 185-mile radius of the smelter, including Glacier National Park and the Cabinet Mountains Wilderness Area, the report said.

Tymko, HiTest’s president, said he’s confident the smelter will be able to meet state and federal air quality standards.

“If this was a business that was highly polluting and damaging to the environment, Washington state is the last place we would look, because Washington has some of the most stringent air quality limits in the U.S.,” Tymko said.

The smelter will use a bag house to scrub soot from its emissions, the consultant’s report said. But capturing the pollutants that cause smog and acid rain isn’t technically feasible and hasn’t been done in the silicon industry, the consultants said.

“Most of the byproducts go up in the stack,” Osterman said.

Some for, some against

Mike Manus, a Pend Oreille County commissioner, said local residents are divided on the smelter.

“About 50 percent say, ‘Great. We need the economic development. We need the jobs,’ ” Manus said. “The others say, ‘Not in my backyard.’ ”

On Sunday afternoon, residents packed the Roxy Theatre in Newport for a 3 1/2-hour meeting organized by Citizens Against the Newport Silicon Smelter.

Mike Naylor, an Oldtown, Idaho, resident, owns 20 acres near the proposed smelter site. He said local officials weren’t forthcoming with citizens. Both Washington and Idaho residents should have been alerted that HiTest Silicon was interested in the PUD property before the sale, he said.

Pend Oreille County sold 14 acres to the PUD last summer. The acreage become part of the land HiTest bought from the utility for $300,000 in September.

“This smelter could destroy our property values, risk our health and our way of life,” Naylor said.

Manus said local residents will have opportunities to weigh in as HiTest works through the state and local permitting process.

“It’s going to be a long, arduous process,” Manus said. “I have full confidence in the state Department of Ecology … that they will hear all the constituents’ concerns … and make sure this is the right business for the area.”

Grant Pfeifer, the Ecology Department’s eastern regional director, said he couldn’t comment directly on the smelter proposal. To date, the only document state officials have received from HiTest is the consultant’s report, which outlines proposed air quality modeling.

However, the state’s review process requires applicants to disclose adverse impacts to the environment – including air, water quality, traffic and public health –and indicate how they plan to mitigate them, Pfeifer said.

Before state or federal permits are issued, there’s a long public involvement process, Pfeifer said. Since the smelter site is adjacent to the Idaho border, the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality also will participate.

In Solar Acres, the Hieseners wonder what their future holds if the smelter is built.

“This is life-altering. We gave up everything to be here,” Axel Hiesener said.

“I feel like our lives are being stolen from us,” said his wife, Theresa.

This story was updated to correct the size of the Kalipsel Reservation.