It’s sprawl - not pests - that pose the biggest threat to Skagit Valley tulip fields

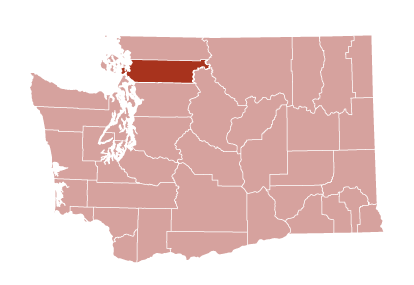

The Skagit Valley, a million acres of rich farmland, sits nearly dead-center between Seattle and Vancouver, B.C.

It’s this proximity to bustling cities that puts an unusual kind of pressure on growers in the Valley, said Allen Rozema, the executive director of Skagitonians to Preserve Farmland.

Since the 1950s the Puget Sound area has lost 60 percent of its farmland. And although changes to county zoning laws and state laws have slowed the sprawl of homes, business parks and roads, Rozema estimates between 50 and 100 acres of farmland continue to be lost every year.

“We call it death by a thousand cuts,” he said. “It’s all these little things that chip away (at farmland).”

And in the past several years, Rozema said the pressure to convert farmland has only grown.

“As the economy gets hotter, as housing gets hotter, that’s when the pressure starts to build up,” he said.

Land loss impacts farmers in several ways.

Mike Flory and Bonnie Branch take a selfie amid a sea of color on Wednesday, April 26, 2017, at Tulip Town near Mt. Vernon, Wash. (Tyler Tjomsland / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

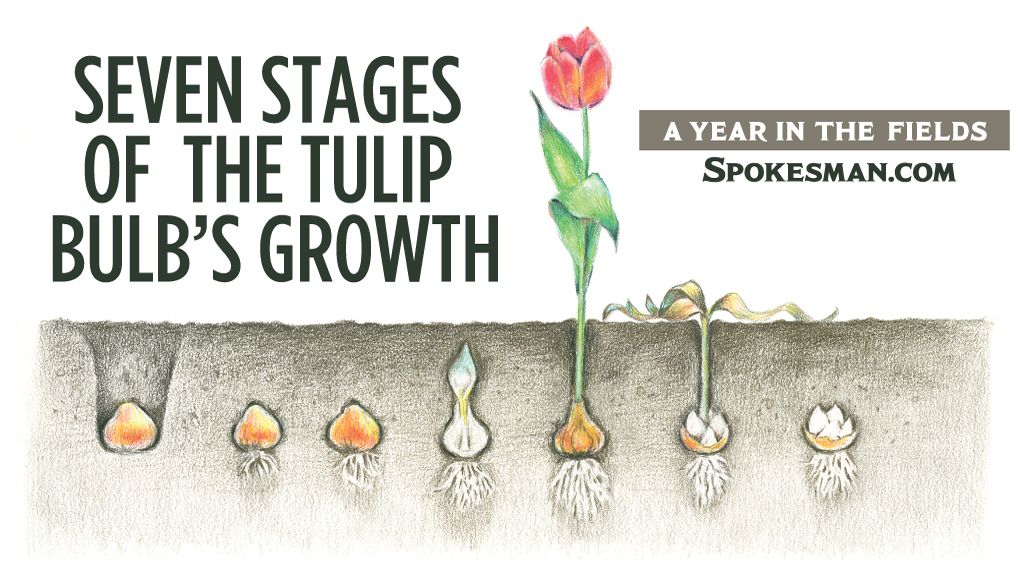

Most of the crops grown in the Valley require long cycles in between planting. For instance, Skagit Valley farmers grow about 95 percent of the United States’ spinach seed. Spinach has a 12-year rotation cycle, meaning farmers can only plant spinach on any given acre of land every 12 years. Tulips are rotated out every three to four years.

In the past, farmers would enter into informal land sharing agreements. One farmer would let his or her neighbor graze cattle on a dormant field. With the loss of farmland to development, that’s becoming harder to do.

“A great analogy is this is a giant landscape-scale (game of) musical chairs,” Rozema said. “So when you pop 50 acres out any given year … it starts to disrupt and play havoc on the crop rotation cycle.”

With the constant threat that a neighbor may sell their farmland, thus threatening any existing land-sharing agreements, farmers are increasingly exiting such arrangements and instead buying their land outright.

“It has forced Washington Bulb to buy as much farmland as they possibly can,” Rozema said.

Although Washington Bulb Co. is one of the larger landowners in the Valley, they still enter into land sharing agreements.

However, Rozema said the Valley’s largest farm, a 6,000 acre operation, no longer land shares with neighbors.

That pressure to consolidate, and grow bigger, is a trend in American farming. A trend that’s exacerbated in the Skagit Valley by development pressure from the nearby metropolitan areas.

“Just like the middle class in America, in farming, large farms are getting larger and consolidating and vertically integrating,” Rozema said.