Researchers unearth century-old mystery in Spokane Chinatown-linked objects found in Riverfront Park

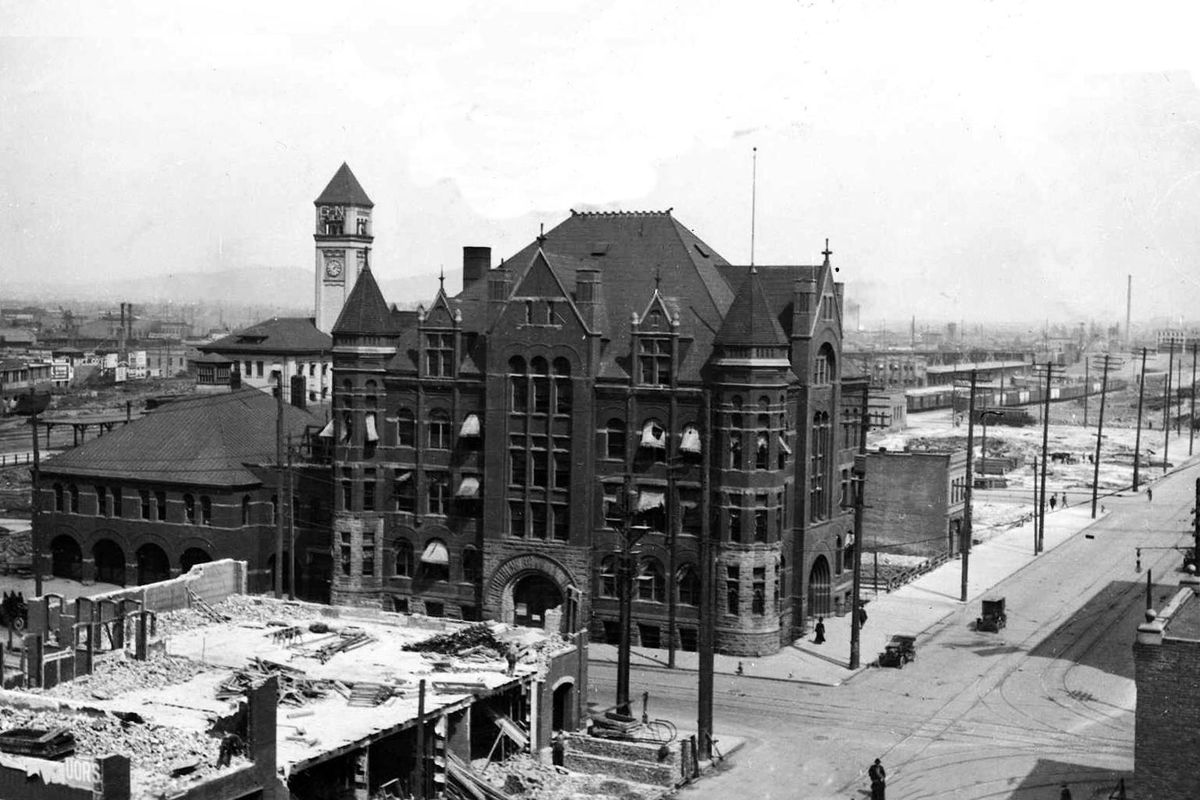

The impressive city hall was built at the corner of Howard and Front St. in 1894, a symbol of Spokane’s prosperity and prestige. Farther east on the block was a row of Chinese mercantile shops and a boardinghouse called the Ondawa Inn, opened in 1903. (COURTESY OF THE NORTHWEST ROOM, SPOKANE PUBLIC LIBRARY / SR)

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misidentified the researchers who helped exhume the artifacts found near the Looff Carrousel. This story has been updated to properly identify the participants.

Researchers digging near the Looff Carrousel this winter unearthed shattered dinnerware bearing Chinese and Japanese markings, perhaps the only remaining relics of a portion of Spokane’s Chinatown swept away by the encroaching railroads.

Yet despite a few tantalizing clues, investigators say some of their most fundamental questions – in particular, the question of origin – remain unanswered.

“These aren’t artifacts where we can say, this is definitely associated with a Chinese privy,” said Ashley Morton, a principal investigator with the Fort Walla Walla Museum overseeing the digging ahead of Riverfront Park’s planned redevelopment.

Following the discovery this summer of slag from a late-19th-century blacksmith shop, Morton and fellow researchers Christopher Casserino, Jackie Corley, and Laura McCullough, of the Spokane Tribe of Indians Preservation Project, found fragments of decorated porcelain in trenches a little over a meter deep. Though not unexpected, given the site’s proximity to an area where hundreds of Chinese and Japanese immigrants made their homes in the early 20th century, there are few historical clues to pinpoint where the items originated.

“What intrigues me about the pieces that they’ve excavated is that I don’t think you can definitively tie that to Chinese or Japanese communities living downtown,” said Rose Krause, a metadata librarian at Eastern Washington University who studied Spokane’s Asian population leading up to World War II. While the pieces bear the hallmarks of Far East design, they’re also typical of an American fascination with exotic porcelain in the early 20th century, she said.

“For the downtown hotels, I think that was a bit of a draw, that you would have these sort of exotic interior designs,” Krause said. “You saw that in the early Davenport Hotel, and then in the Desert Hotel, and other places.”

A second Chinatown

Historical maps of Spokane’s “Chinatown” set the northern border of the district at what was then called Front Street – today’s Spokane Falls Boulevard – and centered on what was called “Trent Alley,” described in newspaper articles and crime records as a den of gambling, prostitution and later bootlegging during Prohibition. The last building in that area was razed to make way for a large parking lot for the downtown convention center prior to the construction of the Davenport Grand Hotel.

Historical records, many of them housed at the Ferris Archives of the Northwestern Museum of Arts and Culture, indicate a separate Chinese corridor developed in the area now known as Riverfront Park. This second Asian hub was erased in the years between the 1889 fire and 1913 when the block was demolished by Union Pacific to make way for the railyards.

The block, known alternatively as the Lotus Block or the Havana Block, housed at least four Chinese and Japanese merchants, according to a Spokane directory of businesses published in 1907: Quong Ying Chun, Sing Fat & Co., Sun Lee Yick and Yee Yuen Hong Kee & Co.

All had addresses on Front Avenue, just down the street from what was then City Hall and the jail. All the more daring, then, was the armed robbery of Sing Fat on Nov. 30, 1913, when a masked man ordered Sue Ah Yen, his wife and three children into a backroom before fleeing into the street with cash, jewelry and Chinese valuables, according to a Spokesman-Review article on the crime.

Boarders, mostly Chinese men over the age of 30, occupied rooms on the second floors of the businesses, according to 1910 federal census data published by Morton and Harrison in advance of their archaeological work. That year, the block had the highest population density in the area – higher even than the city’s jail, which held 59 people at the time of the census.

None of those businesses appear in photographer Ryosuke Akashi’s 1914 photo album and census of Japanese businesses in town, which instead focus on the south side of Front Avenue. Storefronts, restaurants, barber shops and billiard rooms owned by the growing number of Japanese transplants to the area are cataloged, but none bear the name of the Lotus Block businesses.

The brief tenure of the Ondawa Inn

Anchoring the block to the east was a three-story hotel called the Ondawa Inn, which leaves behind the most tantalizing clues of any building in the area. The November 1903 opening of the hotel – described as a combined restaurant, lodging house and free employment office in labor reports from the era – drew an appearance by Mayor L. Frank Boyd and gushing promises from its proprietor, identified in a Spokane Press article only as Captain McClelland.

“Our service room will be one of the most commodious in the city and with the lights all lit in the evening its appearance will be magnificent,” McClelland told the paper.

But in less than a year, the hotel’s manager would find himself in hot water with his staff. In February, the Press reported that McClelland had earned a visit from the trades council for sacking waiters and chefs after failing to balance profits with expenses. By 1909, a different manager had taken over operations of the Ondawa, and the hotel shuttered in 1910 to make way for the “Rescue Mission,” according to archival records of The Spokesman-Review.

At the time of its closing, the Ondawa was listed as the residence for close to 100 lodgers, mostly single men working as laborers or in the trades around town. Most were not from China nor Japan, instead hailing from the Midwest or European countries.

Finding a home for history

The relics uncovered in the park are the property of the city of Spokane, said Fianna Dickson, a spokeswoman for the Parks Department. Morton, the principal investigator on the project, said there will be ongoing conversations about curating the items for future public access.

The team is hoping to get back into the area around the Carrousel, following demolition of the existing structure. In addition to the porcelain artifacts, researchers also found slugs from a Linotype machine bearing street names in downtown Spokane, believed to have originated at the Pioneer Printing Co., one of several publishing firms that also once stood on the south bank of the Spokane River.

Morton said the presence of so many artifacts directly beneath the surface demonstrates much of the history of the area survived soil disruption caused by construction of the railroads and park, and the need to continue surveying as the redevelopment continues.

“There’s still stuff there, from before even when they had the elevated track put in,” Morton said. “A lot of people had been saying it’s really clean, it’s all filled up. But that’s not the case.”

Park officials have authorized up to $293,000 to continue archaeological digs as construction in the park continues, about a third of which has been used already. Dickson said the design of the new home for the Carrousel, scheduled to open early next year, doesn’t call for much additional disturbance of the soil.

“We kept it above ground,” Dickson said. “That’s to create efficiencies, and to avoid digging too deep, because that creates more cost.”

Without specific markings on the porcelain uncovered, or detailed public records about the businesses that once lined the bustling avenue that became the southern edge of Riverfront Park, the remains unearthed near the Carrousel may never have a firm point of origin. But that’s part of the joy of digging up history, said Krause, the EWU researcher.

“In some ways, it’s nice not to have a definitive answer,” she said. “That way, you get to imagine. Which is fun, too.”