This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: Refugee came too far to be greeted with racist fliers

Aung Zaw’s day started well before dawn.

He arrived at 4:45 a.m. Thursday for his shift as a maintenance worker at the Community and Saranac buildings on West Main Street. He started in the Saranac Commons, and headed down to the Community Building at about 6:40, he said.

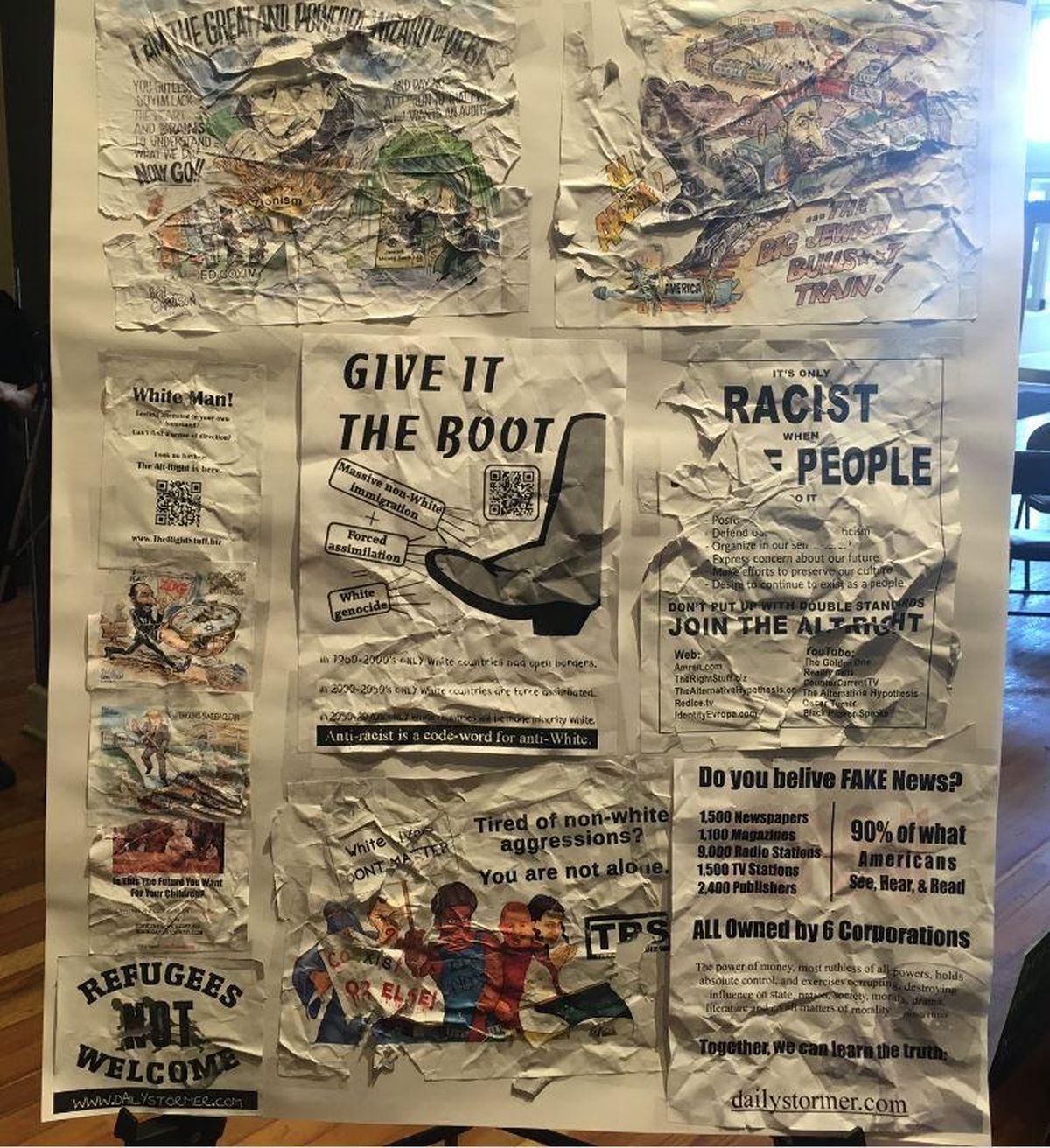

He found the glass front doors plastered with hateful, racist fliers.

“Tired of non-white aggression?” one of the fliers said. Others included hateful Jewish caricatures and an image of Trump with a broom, sweeping out Obamacare and open borders.

Then there was this: “Refugees NOT Welcome.”

Zaw – a 37-year-old Burmese refugee who says he feels quite welcome here – knew just what to do. He took the fliers down, crumpled them up and threw them in the garbage where they belong. Others retrieved them later to report to the police and rally community opposition.

Did it bother him? Make him angry or upset?

Zaw waved his hand dismissively.

“I don’t care,” he said. “This building – everyone is like me. … Good place. All good people. I don’t care about that.”

Zaw’s long, difficult road from a refugee camp in Thailand to Spokane has been full of enough strife and difficulty that a few ignorant posters don’t throw him off. But they should throw the rest of us off – a reminder, after so many of us got so exercised about that Guardian story, to pay as much attention to the insult from within as the insult from without.

The messages on those fliers – some of which were also posted at the local Democratic offices and a nearby coffee shop – share a source with the vandalism of the Martin Luther King Jr. center and other recent white supremacist activity: They are flatulent bubbles arising from the swamp, a fetid stew that waxes and wanes and sometimes seems to die, but doesn’t.

That’s what’s really unwelcome here.

Zaw, though – he’s more than welcome, at least as far as I’m concerned. And his story is one that more of us should know here, as we discuss our national approach to welcoming, or rejecting, refugees. He agreed to talk about it this week, though he did not want to be photographed.

Zaw’s home country is now officially named Myanmar, but many still refer to it as Burma. The country has a fractious and war-torn history, with tens of thousands of refugees fleeing violence and civil war in recent decades. Many of the refugees are members of ethnic minority communities, including the Karen and Non.

More than 100,000 have fled to camps in Thailand near the border, and some have stayed there for more than a decade. Many have been resettled to other countries as part of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees program, and some have begun returning to a reforming Myanmar. There is a community of about 500 refugees from Myanmar in Spokane.

Saw Gary is a 30-year-old Burmese refugee who works as the pre-arrival and housing coordinator for World Relief Spokane, and he helped Zaw and his family settle in Spokane. His own story is complicated and heartbreaking: His parents fled Burma, he was born in Thailand but was not a citizen, so he felt twice-rejected. He’s now an American citizen and wants people to know the stories of refugees before they pass judgment.

“I just want people to learn the story of refugees that have resettled,” Gary said. “The stories can be so painful.”

Zaw was born in 1980 in the town of Thanbyuzayat. He and his parents first felt the disruptions of a country in political upheaval when he was 8 years old and they fled their home in the midst of protests. Years later, they were driven from a different village by government soldiers to make room for a natural gas pipeline. Zaw says soldiers carried out the evacuation at gunpoint.

“They say a week, we need to move,” he said. “Somebody who doesn’t move, they kill.”

He and his family moved a few miles away, where they farmed rice. But they were close enough to hear the soldiers clearing out others who hadn’t gotten out of the way.

They could hear the guns; he mimicked the sound in a rapid whisper: “Pow-pow-pow-pow. Pow-pow-pow-pow.”

Were the soldiers shooting in the air, as warnings?

“No, no, no,” he said. “They never shoot their gun in the air. They shoot the people.”

So he and his parents fled again, into the forests and toward asylum in neighboring Thailand. They were separated for a while – his mother urged Zaw, then 28, to run ahead and save himself, he said. After about a month living unsheltered in the forest, they found a Thai village and were directed toward a nearby refugee camp.

Zaw lived there for more than seven years. He stayed in simple, crowded bamboo houses, with almost no latrine facilities and health care, and little food and water. He met his future wife in a camp church – both are Christian – and they started a family. She’d been in camp for almost 20 years.

They began seeking relocation to America through the UNHRC. The process took roughly two years, and involved repeated interviews and screenings, including a final one in the American embassy in Thailand, he said. He and his family moved to Spokane with the help of World Relief, a nonprofit that resettles about 600 refugees a year in Spokane (though the Trump administration’s travel ban and overall approach has created uncertainty going forward).

Zaw remembers the date of his revival precisely: May 25, 2015.

“That changed my life, so I know that,” he said. “We were born again. That date is new life.”

Gary remembers that Zaw wanted to go right to work. “That first day he landed. ‘Hi. Can you find me a job?’ ”

Zaw has worked at the Community Building – which houses the NAACP, the Center for Justice, the Peace and Justice Action League, a preschool and other offices – for about a year and a half. He came on a temporary work visa, got a green card, and now has permanent residency, with an eye on working toward citizenship. He and his wife have three young children, have saved up enough for a down payment and are currently shopping for a mortgage to buy a home.

“We have future, right now,” he said. “When we stay in refugee camp, we had no future. I hope for my kids, they have a good future.”