Rhea Seddon, pioneering astronaut and surgeon, to speak at Gonzaga

When she was preparing for her first NASA mission, surgeon and astronaut Rhea Seddon remembered there were some concerns about whether a woman’s body could adapt to space as well as a man’s.

Her team, which focused on life science research in zero-gravity, did tests using equal numbers of men and women as test subjects. They proved what was no surprise to Seddon: Women adapted exactly the same.

“It was nice to have rigorous scientific data that proved it instead of just saying, ‘Don’t worry,’” she said.

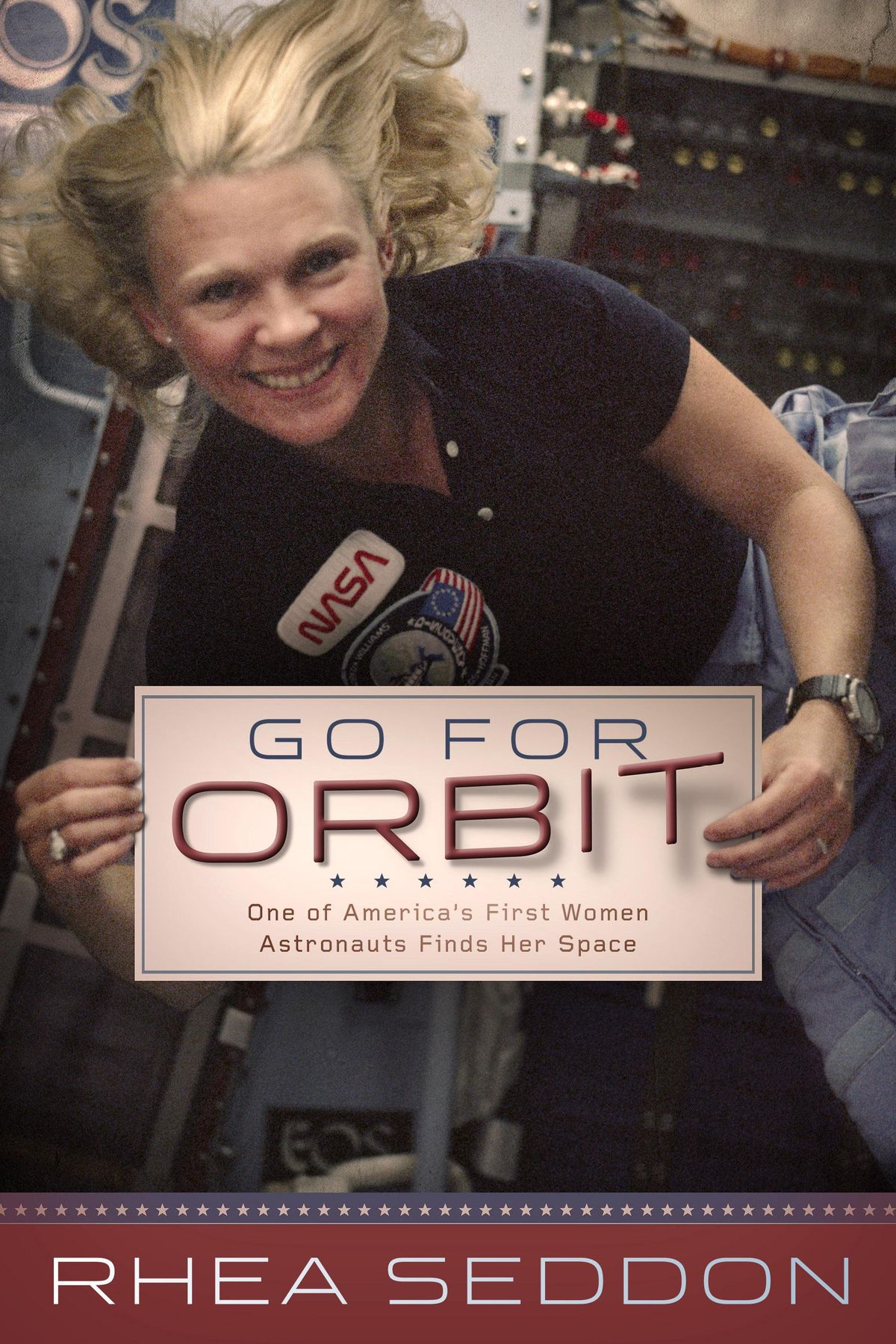

Seddon, who was inducted into the Astronaut Hall of Fame in 2015, will speak 7 p.m. Monday, March 27 at Gonzaga’s John J. Hemmingson Center. Her talk shares a title with the autobiography she published in 2015, “Go For Orbit.”

Her accomplishments include three flight missions, as well as becoming a surgeon, getting a pilot’s license and going back into the health care sector after 19 years with NASA. She said her experiences changing careers several times and beating the odds as a pioneering woman are of interest to students, who are often trying to figure out next steps.

“They always like to know, ‘How did you do that?’ and ‘Why did you choose that’ and ‘Which parts were tough?’ ” she said.

As a young girl, Seddon was interested in the space program and said she wanted to be a part of it, but she knew “they didn’t take women and they only took pilots,” she said. She decided to go to medical school and pursue surgery because she knew she would find the work interesting and challenging. But she also thought a surgery background would make her a more attractive astronaut.

“I always thought maybe someday they’ll let women in,” she said. A classmate told her about flight school, and she got a private pilot’s license too, hoping someday she could be a rich doctor with her own plane.

She enjoyed flying as a hobby and knew a flight background would help her apply to NASA, “thinking one was realistic and one was totally unrealistic,” she said.

Another doctor who worked with her had done research with NASA and told Seddon they were going to take their first mixed-gender class of astronauts. She filled out the lengthy civil service application, gathered references, “sent it all in and crossed my fingers.”

In 1978, she was one of six women accepted into a 35-person astronaut class. She said the women were treated well and made it clear they belonged there and were capable of doing the job.

“It all came together for me at just the right time. Part of life is luck and being in the right place in the right time and doing the hard work ahead of time to be ready,” she said.

She would later meet her husband, a fellow member of her flight class, and have a child while training for research in space.

Women had already been at NASA for several decades, and their stories have been popular lately thanks to the pioneering black women mathematicians and engineers featured in the book and movie “Hidden Figures.” Seddon said she loved the movie, both for its accurate portrayal of astronaut John Glenn, and for highlighting a group of overlooked women.

“They certainly faced an awful lot more discrimination than we ever did,” she said. “Luckily times had changed by the time we got there.”

Her first mission took off in 1985 aboard the Discovery shuttle, which deployed a communications satellite. Her second and third missions, in 1991 and 1993, focused on the effects of time spent in zero gravity on the human body. There were many unknowns: How quickly do bones deteriorate? How does the immune system respond when it’s not around new microbes all the time? How does balance recover after a return to earth?

She and other scientists used rats to see what might happen to humans. It was known that bone density will drop in space, but her team found rats that grew new bones in space had much weaker bones than those that would grow on earth.

“It doesn’t help to keep the calcium in your bone if it’s not good bone,” she said.

Their work led to exercise protocols, still used on the International Space Station, to help astronauts minimize calcium loss. They were also able to quantify changes to the body and come up with explanations for them.

Seddon and her husband left NASA after the U.S. began working with Russia’s space program following the Cold War, and declared astronauts had to be willing to spend up to two years in Russia. With three children at home, she went back into health care, working as assistant chief medical officer for Vanderbilt Medical Group before starting her own health care training company in 2005.

She said she doesn’t follow the ongoing research on the International Space Station closely, but does keep in touch with colleagues from NASA. Once a year, they go back to the Johnson Space Center for a physical exam to make sure they have no long term effects from their time in space.

“A bunch of us are still doing pretty well,” she said.

Her talk is put on by a number of Gonzaga departments.