Caught stealing: Bob Cress, baseball player and jail-breaker

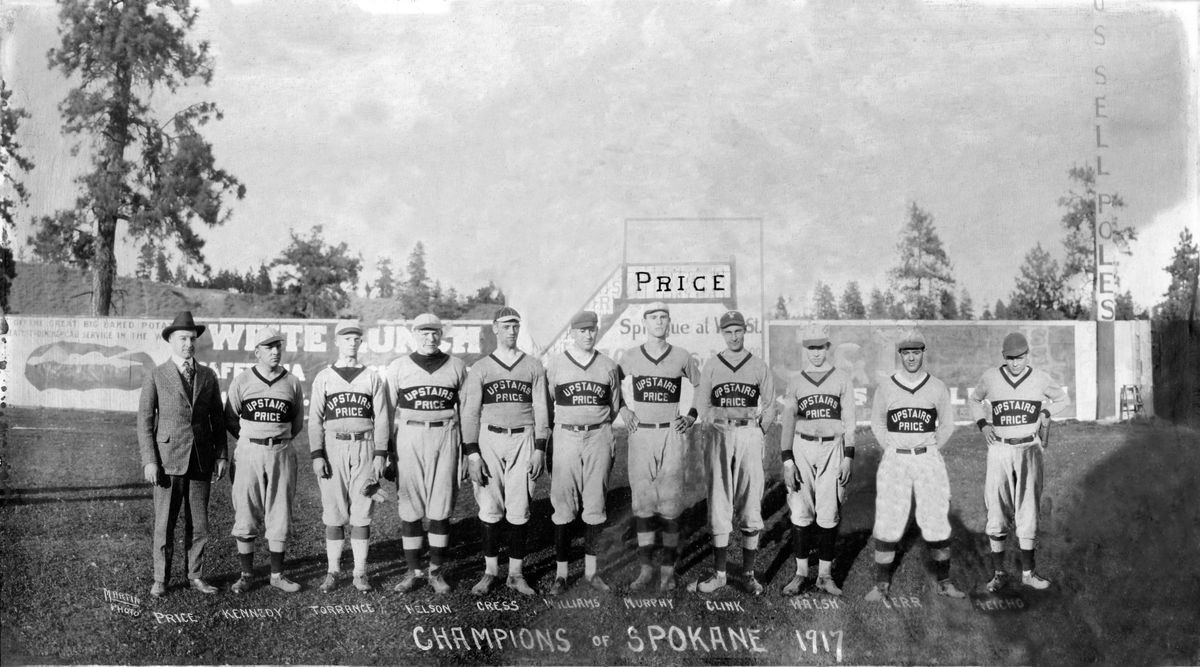

Bob Cress, fifth from the left, poses with members of the Upstairs Price team that won the 1917 Spokane City League championship. Sponsor W.B. “Bert” Price and player-manager Jay Kennedy are on the left followed by Roscoe “Torchy” Torrance, future Seattle baseball executive and prominent University of Washington booster. Spokane Indians manager Nick Williams, future Idaho state senator Art Murphy and standout pitcher George Clink are to the right of Cress. Williams signed on after the Northwestern League folded in mid-July. (Juanita McBride / Courtesy)

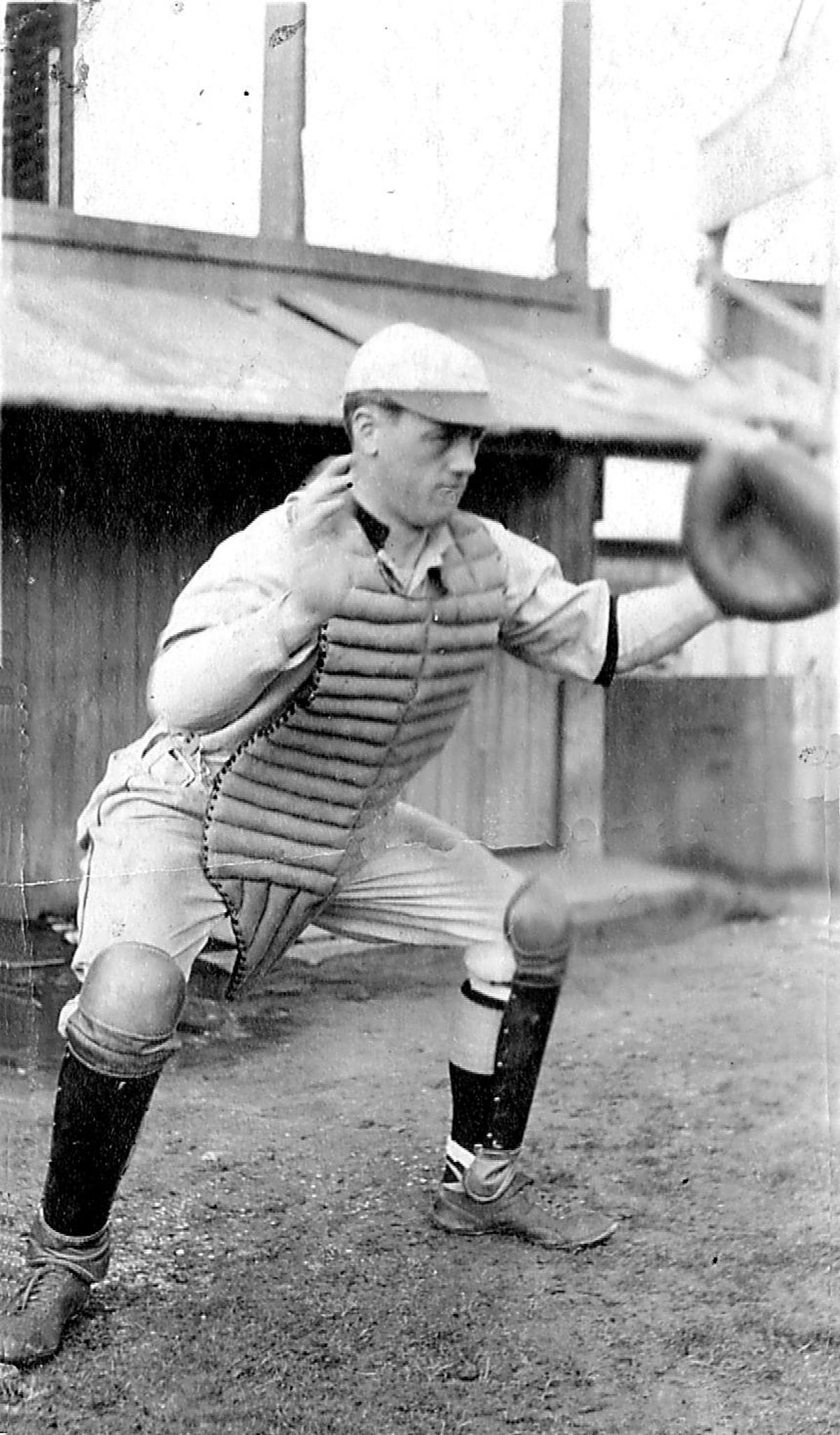

Clearly, Cress yearned to be a baseball player, and, for a decade or more he was, a catcher who played a bit with the Spokane Indians, parts of seasons with other professional teams and pursued opportunities, short and long, in the Pacific Northwest’s best semipro leagues.

He also spent a third of his adult life in jails and prisons, became a folk hero who pulled off incredible escapes and left some of his descendants torn between dismay and admiration.

When the clock ran out on his baseball ambitions, and the 18th Amendment abolished the manufacture, sale and transportation of alcoholic beverages, Cress turned to the liquor business. By the time a newspaperman shot him full of holes, he had become an importer of sorts, acquiring legal goods in British Columbia and turning them over to a dealer he met at the border. In his case, acquiring meant stealing.

When arrested, he often escaped. Undaunted by years in Western Canada’s toughest lockups, he outdid himself by burglarizing the Spokane Armory. Then he graduated to U.S. federal prisons, and they couldn’t hold him either.

Cress generated a lot of news. If he had only wanted to see his name in headlines, he could have skipped the baseball.

From a pioneer family that traces to a Revolutionary War hero, Robert Legard Cress was born Nov. 28, 1891, in tiny Chilhowie, Virginia, not far from the Tennessee and North Carolina borders. Fifth among 11 children, his immediate family was dirt poor. Relatives say his father, Ezra, was a drunk. His mother, the former Bettie Overbay, did her best to hold the family together. It was hard work. At least three of her children became criminals.

About 1907, the entire family, except for an older boy, came west and made their home in Opportunity, enveloped today by the city of Spokane Valley.

By then, Bob had an eighth-grade education and was ready to play some ball. Although he resembled his mother, he sure as hell looked like a ballplayer, a rangy, 6-foot right-hander, tall for the time, with straw-colored hair and blue eyes. He had a strong, accurate throwing arm.

Sketchy records say that between 1908 and 1911, Cress played some in the semipro Spokane City League, which developed its share of future pros. In 1911, he also played a bit for Butte, one of Spokane’s rivals in the professional Northwestern League. The next spring, he went to camp with Missoula of the Union Association., where the manager, former Washington Senators catcher Cliff Blankenship, seems to have taken Cress under his wing.

Blankenship, mostly remembered for signing Hall of Fame pitcher Walter Johnson on a scouting trip to Idaho, was a fine receiver himself and had the makings of a championship team, so he couldn’t keep a relative novice. But he may have paved the way for Cress to join the Ogden franchise. Cress played there a bit through June and finished the summer with the semipro Anaconda Independents.

In 1913, he joined Baker, Oregon, of the Western Tri-State League, where, if nothing else, he gained a reputation as an “o-fer” kind of guy, someone whose box score lines often read 0 for 3 or 0 for 4. After he managed only 18 hits in 98 at-bats – a puny .184 average – the Golddiggers released him in June.

After the season, on Saturday, Sept. 13, Cress and his roommate, pitcher Clayton Coleman, took in the Pendleton Round-Up, camping alongside the Umatilla River. After a night on the town, Coleman awoke to find $200 cash missing from his wallet. When Cress told police a story they didn’t believe, they searched him, found Coleman’s money and took him into custody.

Coleman, perhaps embarrassed, declined to press charges, so Cress was a given a suspended sentence. Nonetheless, his mug shot began to circulate among Northwest lawmen.

On Nov. 30, 1913, Cress married Emma Brown, whose father farmed near Baker. Their son, Bobby, was born in early June. By then, Cress had caught on with the WTL’s Walla Walla Bears, whose roster included several future Spokane Indians, including former North Central High School student Earl Sheely, who spent nine good seasons as a major-league first baseman. Walla Walla had a championship team. Cress didn’t stick.

Although it isn’t clear where he played in 1915 and a couple later years, Cress often lived in or near Baker, so he probably caught for several Eastern Oregon semipro clubs. In 1916, he spent spring training with San Francisco of the Pacific Coast League, began the Northwestern League season playing for Vancouver in Spokane, caught a couple of games for Spokane’s championship team and finished up with Hamilton, a pennant-winner in the semipro Western Montana State League. In August, Blankenship signed him to a Salt Lake City contract for 1917.

On a roster crowded with six former Spokane players, including Sheely and catcher Truck Hannah, Cress remained with the PCL team for almost three months. Hannah, however, played almost every inning, so Cress appeared in only nine games before he was released on July 8. A week later, he joined the semipro team in nearby Tooele and wound up the summer helping Upstairs Price, which represented a downtown men’s store, claim the Spokane City League title. Cress caught the last three games and went without a hit.

He was in Spokane in August 1918, when the FBI arrested him for draft evasion. On March 10, 1919, while living in Republic, he and Emma welcomed a daughter, Eva.

The 1920 federal census, taken in January, lists Cress as a farmer in Plummer, Idaho, but by summer, he was busy on the baseball diamond. He caught for the town team in Waterville, Washington, spent more time in the City League and, as the Indians – now managed by Blankenship – ended their professional season, he went behind the plate for five games that produced a familiar result. Eighteen at-bats, three hits, a .167 average.

The Volstead Act, which implemented Prohibition, had taken effect on Jan. 17, 1920. When opportunity knocked, Cress made a career change.

The family’s historians, granddaughter Juanita McBride of Spokane, who is Eva’s daughter, and great grandnephew Will Cress of Dublin, Ireland, have uncovered no anecdotal evidence that describes their ancestor’s next 20 years. Like you and me, they read about it in a newspaper.

On April 1, 1921, Cress faced federal charges for operating a still at Valleyford. In September, he was charged with bootlegging.

On Nov. 29, in Harrington, the town marshal recruited three men to watch a suspicious car parked by the office of the Harrington Citizen. When Cress and Harry “Bush” Hallett of Davenport showed up, they were arrested and herded into the newspaper building. Cress, packing a large caliber automatic pistol, was disarmed.

Moments later, Cress snatched up the gun, which had been set on a counter, and demanded his freedom. But assistant publisher Herman Bassett, believing Cress might fire, emptied his own .25, shooting Cress through the jaw and wounding him in both arms and one side.

Five bullets were removed in Spokane’s Sacred Heart Hospital, including the one that had lodged in his throat. Apparently unfazed, in the first of many candid, well-spoken jailhouse interviews, Cress told a Spokane Chronicle reporter that he had been in the business for three years and that he thought the special deputies, who wore no badges, wanted his five cases of branded whiskey. He added that he and Hallett had just stopped in town on their way to Ritzville, although, when searched, their pockets held checks from local residents. Eventually, he went to jail for 60 days.

On Aug. 17, 1922, the Grant County sheriff arrested Cress and another man in Soap Lake. Their car held 18 bottles of Canadian whiskey.

On April 21, 1923, Cress was convicted in Chelan County superior court of bootlegging and possession of intoxicating liquor. Awaiting trial, he had called attention to himself by throwing bottles from his car at a Wenatchee policeman who had tried to arrest him for speeding.

On Dec. 3, two armed masked men intercepted Daniel Docksteader, who was delivering 22 cases of legally purchased liquor to the border crossing just west of Grand Forks, British Columbia. The bandits took Docksteader’s car, expecting to find twice as many cases, and left his passenger, who said he was the buyer, tied up in their car.

Investigators soon identified Bob Cress as the passenger and his baby brother, Dan, as one of the hijackers. They were nearly as certain that another brother, Joe, recently paroled from the Washington State penitentiary, was the other. Establishing a pattern for future mistakes, Bob was arrested when he stepped onto Canadian soil while describing the hijacking to Spokane’s chief deputy sheriff, Floyd Brower, and provincial investigator W.R. Dunwoody.

There were, by the way, no extra cases of liquor.

Bob and Dan Cress were sent to the British Columbia prison in New Westminster, sentenced to five and four years respectively. Joe Cress couldn’t be found. He had fled to California to avoid prosecution for an attempted bank robbery in Rosalia.

Bob Cress was paroled on Aug. 27, 1927. Only 17 days later, after Vancouver’s Cordova Street liquor store had been burglarized, U.S. customs agents apprehended him. He was driving a truck loaded with the missing 53 cases of liquor. Headed east toward Hope, B.C., he had accidentally crossed the border.

Cress was held for extradition in Bellingham, but he escaped on Oct. 26 and was arrested again, back across the border in Vancouver, six days later. Then he was sentenced to another five years in New Westminster.

Released in the spring of 1932, he began to board with George Fish, an old friend who lived with his wife, Edith, near Corbin Park. Before mid-summer, Canadian police wanted him in connection with a Greenwood, B.C., burglary that fit his M.O. As dawn broke on July 2, a man had been seen loading cases into a British Columbia Telephone Company truck. Liquor worth $3,000 was missing.

Then, on Monday morning, Sept. 19, the ballplayer turned rumrunner outdid himself.

About 1:15 a.m., in downtown Spokane, Sgt. H.B. Thoreson, the night watchman, spotted a man on the Pacific Avenue fire escape of the National Guard Armory. Thoreson led the man to the lighted front entrance on Second Avenue and began to search him. From behind, another man, probably driving the getaway car and possibly Dan Cress, struck Thoreson on the head.

“Crack him another one on the beezer!” commanded the first man. The second man did, and Thoreson crumpled to the pavement, seriously injured. Seventeen .45 automatic pistols, including Thoreson’s, and some uniforms had been stolen.

On Oct. 1, Cress was involved in a minor head-on collision with a B.C. Telephone car on the highway north of Trail and, the other driver noticed, he had broken bottles leaking in his car. Was it a coincidence that the provincial liquor store in Blairmore, Alberta, five hours east, had been burglarized just that morning?

Cress, with papers identifying him as J.W. Robertson, entered Canada again on Oct. 18, accompanied by a woman he said was his wife. They had, he said, plans to spend a day in nearby Grand Forks. Two days later, between Balfour and Nelson, 100 miles east of Grand Forks, Cress was on the wrong side of the road when he collided with another B.C. Telephone car, this one driven by district manager C.E.G. Fisher. Both cars were disabled.

When Cress, now saying he was J.W. King, became belligerent, Fisher called the provincial police. A constable transported Cress to Nelson and, recognizing similarities with the Oct. 1 accident, he was held for questioning. After a fingerprint check clarified his identify, officers searched his Ford and found machinist’s shears, a large pry bar and a hidden pair of .45-caliber automatic pistols. One pistol belonged to Thoreson; the other came from the armory.

Cress was arrested, charged with the Greenwood burglary, and U.S. federal authorities staked their claim. Because the Canadians had priority, Cress remained in the Nelson jail. But the U.S. lawmen returned home with his female companion, who turned out to be Edith Fish.

On Oct. 26, after a preliminary hearing in Grand Forks, Cress returned to the Nelson jail. On Wednesday evening, Nov. 23, he sawed through his cell’s fiberboard ceiling, crawled over the women’s quarters and escaped through the yard. He expected a getaway car. When it didn’t show up, he took off through the snow and made it as far south as Salmo before he was captured.

He went on trial the following Monday. Although the evidence appeared to be damning, Judge J.R. Brown acquitted him. The longtime jurist said the time frame described by witnesses made it impossible to prove Cress was not elsewhere, as he had claimed, when the burglary was committed. Instead, for the escape, Brown gave him a year at hard labor.

Two days later, accompanied by a pair of constables and hobbled by a 50-pound Oregon boot, Cress left for Vancouver’s Oakalla farm prison. As their train pulled out of Carmi, a mining village northwest of Grand Forks, Cress, using his overcoat as a shield, dove through the glass of the smoking-car’s window and hobbled into the woods, setting off a manhunt throughout the Kettle Valley.

Cress was recaptured on Dec. 5. Believing he had crossed safely into the U.S., he was found sleeping, almost 50 miles away, in a barn near Bridesville, fewer than three miles from the border. Wrong again.

After barely six months of freedom, he was back in prison. And when he was released, a year later, he was met with a surprise. Authorities from Lethbridge, holding a warrant for the Blairmore burglary, met him at the gate. Jailed in the Alberta city, Cress received an 18-month sentence for that but appealed and, acting as his own attorney, talked his way out of it, using the same argument that had worked in front of Judge Brown.

On Feb. 14, 1934, Canadian authorities escorted Cress through the checkpoint at Sweet Grass, Montana, north of Great Falls. This time, U.S. marshals were waiting.

Days later, after Cress had reached Spokane, the Chronicle mentioned that the prisoner was well dressed with a pleasant smile and an easy way of conversation. He talked about his baseball career and his preference for jails in the states. He said he now spelled his name Kress.

He faced the armory charges on April 4. During a trial that lasted only two days, Thoreson identified Cress as the man on the fire escape, and the two pistols were brought into evidence. The jury convicted him of breaking and entering and for stealing government property. Newspaper accounts don’t mention his accomplice. Judge J. Stanley Webster sentenced Cress to five years on McNeil Island, the federal prison offshore from Tacoma.

In the morning of April 23, 1935, barely a year later, he escaped, commandeering a boat by knocking a fellow trusty overboard and heading northward across Puget Sound. The boat ran out of gas. Given little choice, he grounded it near Salmon Beach and tried to hide himself in the underbrush. The prison’s three bloodhounds found him before lunch.

On June 25, he told a federal judge that prison guards had beaten him, causing injuries that made him insane. Nonetheless, on Oct. 29, his sentence was increased to 10 years, and he was transferred to the prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

By summer, still complaining of mental problems, he occupied a bed in Leavenworth’s hospital ward while undergoing evaluation. He went missing on July 22, 1936, but guards found him on the roof in the middle of the night, armed with a knife and a lasso. When he resisted, one of the officers fired his shotgun, wounding Cress in the head.

Newspapers from Pittsburgh to Oakland, California, covered the escapes, sometimes on page one. This paper, the Chronicle, the Nelson Daily News and the weekly Grand Forks Herald played it big. An Associated Press report called him “the Pacific Northwest’s champion jail-breaker.”

The Department of Justice reacted by shipping Cress to its medical center in Springfield, Missouri, for treatment of his “peculiar mental make-up.”

Just past his second anniversary in federal prison, on April 13, 1937, Cress checked into Alcatraz, the system’s most secure facility, in San Francisco Bay. Afterward, he must have been a model prisoner because, before the 1940 census, he was back at McNeil Island and, on Oct. 8 of that year, received his conditional release.

Cress returned to Spokane, apparently a changed man. He worked on the final phase of Grand Coulee Dam construction and spent a portion of the next several years in Alaska. Through the 1940s, he visited his grandchildren, who lived here. Long divorced from his first wife, in 1952, he married a recently widowed pharmacist’s wife, Vivian Swanson, and relocated to Portland. There, he seemed to live an ordinary life as a carpenter.

Juanita McBride, born after her mother’s second marriage, remembers her grandfather’s visits.

“He loved to spend time with us,” said McBride, the Eastern Washington Genealogical Society’s longtime volunteer librarian in the downtown public library. “We could sense there were things we didn’t know that our parents wouldn’t discuss, and I’m not sure how much my mother actually knew about his history. But he always seemed to be happy.”

She marvels a bit that, judging by news reports, Bob Cress pointed guns at people but didn’t shoot and may have never injured anyone. He was a burglar, not a robber, who, in the minds of some, provided supplies that filled a demand.

“And when you think about it,” she said, “during Prohibition, there must have been hundreds of people around here doing some of the same things.”

When Joe Cress was paroled in 1958 after more than 40 years in the Washington state penitentiary, he rented an apartment in Vancouver, Washington, but often stayed with Bob and Vivian.

Both men died in 1963. When Bob Cress passed away on April 3, he was 71.

Sue Adrain of the Boundary Museum Archives in Grand Forks, community historian Greg Nesteroff of Nelson, and Marge Womach of the Harrington Public Library contributed additional research.