Spokane schools’ summer STEM camps combat out-of-school slide

On a hot July day, Maudie Johnson, 9, is trying to solve a homicide.

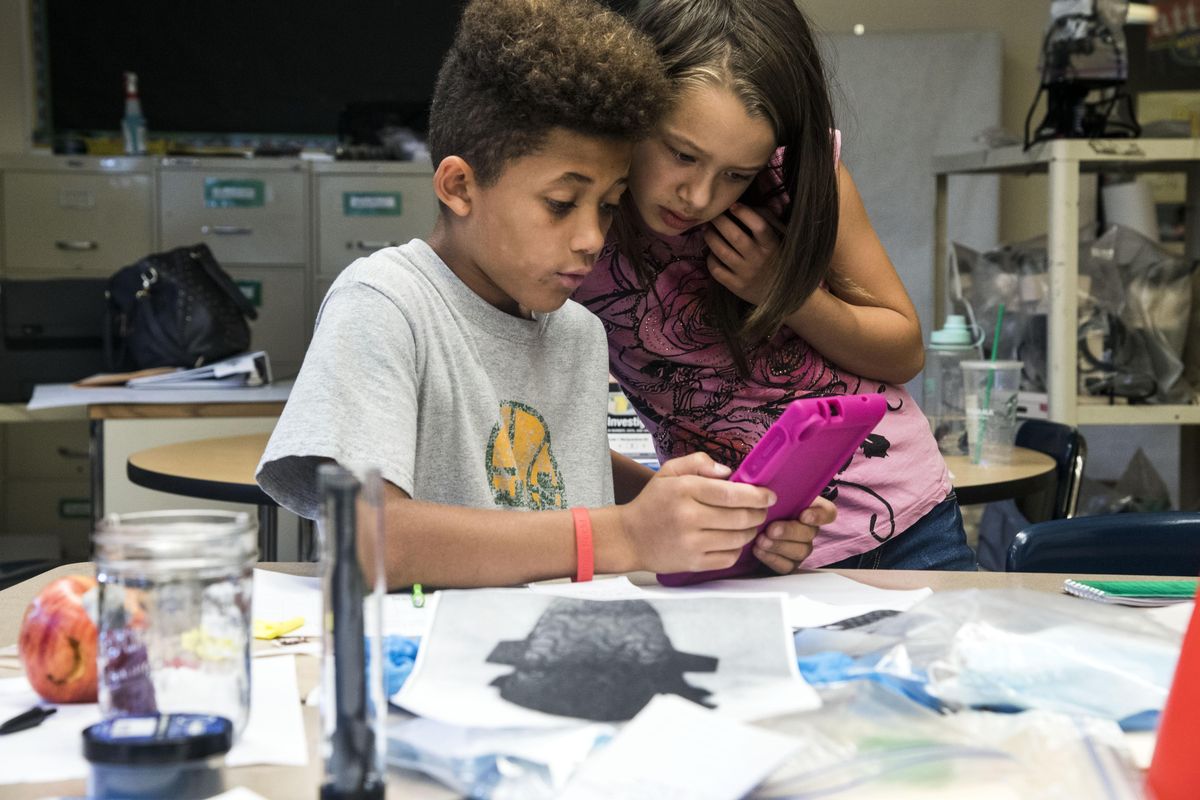

She’s bent over a Kindle, comparing and contrasting footprints taken from a crime scene down the hall. Nearby, another child examines what is purported to be blood splatters taken from the wall of the room.

Johnson was one of about 15 kids enrolled in Spokane Public Schools’ Camp Crime Scene at Sacajawea Middle School on Wednesday.

And although the work looks suspiciously like chemistry and math, Johnson couldn’t be happier.

“I’d probably be sitting in my house being miserable,” she said when asked what she normally does in the summertime. “We don’t have much to do sometimes.”

That’s part of the reason Spokane Public Schools runs a series of weeklong STEM camps throughout the summer, said Lisa White, director of the district’s after-school and summer STEM camp programs.

“Just imagine going to school every day for nine months … and then all of a sudden nothing,” White said.

That sharp drop in activity can cause problems for students both academically and socially. According to a review of research published by the Johns Hopkins School of Education in 2010, most students lose about two months of “grade level equivalency” in math over the summer. This loss is commonly referred to as “Summer Slide.”

By packaging STEM learning in a fun and engaging way, White hopes to counteract the phenomenon.

The camps are also a matter of equity, she said.

“The research suggests that families that are wealthy spend a much higher percentage of money on extracurricular activities,” White said.

According to the Johns Hopkins review of research, low-income students lose more than two months in “reading achievement” over the same period, despite the fact that middle-class peers make slight gains.

“You’re really blessed if you have someone at home who can say, ‘OK, today we’re going to learn about this, or we’re going to the library,’ ” White said. “But for some kids that isn’t happening.”

For years in elementary school, that was camp counselor Taylor Dewey-Buchanan’s experience.

“I didn’t really have a lot of opportunity to further my education, so I did experience that slide,” Dewey-Buchanan said.

Both of Dewey-Buchanan’s parents worked, so on most summer days she stayed at home and baby-sat her younger sister. That started to change for Dewey-Buchanan in the seventh grade, when she realized she wanted to be a forensic scientist. She started researching the topic obsessively, she said.

Now she’s a senior at Grand Canyon University. For the past two summers, she’s worked at Spokane’s Summer STEM camp, leading Camp Crime Scene.

“We try to put a nice twist on education and make it more fun,” she said.

Programs like Spokane’s Summer STEM camps are vital, said Rachel Gwaltney, director of policy and partnership for the National Summer Learning Association.

Educational loss is particularly damaging to low-income students, she said. By the end of fifth grade low-income students can be two to three years behind their wealthier peers in reading and math.

Summer learning programs may be at odds with what Gwaltney calls an “idyllic” view of summer break, one in which children play outside with friends, go to the library and relax from the pressures of school. That view has holes, she said.

“You know what they’re doing. They’re sitting at home watching TV,” she said. “They’re watching over their younger children. They’re being told by Mom and Dad, ‘Stay at home,’ because it’s not safe.”

The National Summer Learning Association is a nonprofit organization that focuses on summer learning programs nationwide.

One of the NSLA’s primary goals is lobbying Congress to preserve the 21st Century Community Learning Centers. The program is the only federal source of money for summer learning programs.

President Donald Trump’s proposed budget would eliminate funding for the $1 billion program. The program serves about 2 million students in high-poverty, low-performing schools nationwide, according to National Public Radio.

Gwaltney said the program has bipartisan support in Congress, so she’s hopeful that it won’t be cut. In fact, Washington Sen. Patty Murray is one of the program’s biggest advocates, Gwaltney said.

Spokane doesn’t receive grant money from the 21st Century Community Learning Centers program.

Providing summer learning options doesn’t have to be complicated, Gwaltney said. Activities as simple as library programs that kids can drop into, or free swimming lessons, provide big benefits.

“We see that it doesn’t take a lot to provide opportunity for young people,” Gwaltney said. “It’s really a matter of public will.”

White, the director of Spokane’s Summer STEM camps, said the camps are intentionally cheap. For $85, children can attend the four-day camps, with snacks and meals included. Scholarships are available to families in need, White said. The camps are largely funded through grants and donations. Additionally, Spokane Public Schools funds White’s salary.

The goal is to get as many children into camp as possible, White said.

“Your brain is a muscle, and if you’re not using it, it will atrophy,” she said.

Editor’s note: This story was changed on July 23, 2017. A previous version incorrectly identified the amount of time it takes for low-income students to fall behind their wealthier peers academically.