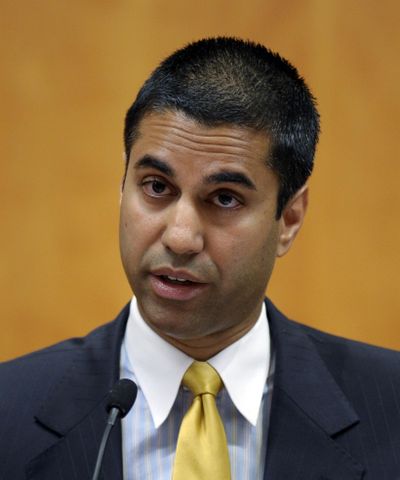

Analysis: What President Trump’s new FCC chairman thinks about net neutrality

You may have heard that President Donald Trump’s new FCC chairman, Ajit Pai, is a critic of the government’s net neutrality rules – the regulations barring Internet providers from blocking or slowing down your websites.

The fate of the rules has been in question ever since Trump clinched the election; approved by a Democratic majority, the net neutrality regulations are about as hated by Republicans as Obamacare is in the health care sector. Analysts widely expect Pai to roll back the net neutrality rules somehow. But exactly what that looks like is unclear. Although Pai on Tuesday declined to say whether he’d enforce the rules on Internet providers, he did shed some light on what he thinks about the issue.

“I favor a free and open Internet and I oppose Title II,” he told reporters. “That’s pretty much all I can say.”

Below, we’ll unpack what all this means for the future of the Internet.

So, is Pai for or against net neutrality?

In plain English, Pai is saying he’s in favor of the idea of net neutrality; he just doesn’t like the FCC’s policy of regulating the Internet providers with Title II of the Communications Act. More on that in a minute.

I’m confused. How can you be for net neutrality but against the FCC’s rules? Aren’t the rules “net neutrality”?

The FCC regulations are aimed at preserving a free and open Internet, but they aren’t technically synonymous with net neutrality. The regulations are simply the government’s attempt to defend net neutrality, which is a broader idea about how the Internet should work.

You’re saying there are other forms of net neutrality out there?

Well, yes and no. The whole concept of net neutrality is a little fuzzy to begin with, and how expansive or restrictive it should be is somewhat subject to interpretation. This is how we got the whole debate over what some called “weak” versus “strong” net neutrality, and it’s what prompted comedian John Oliver to call Tom Wheeler, the former FCC chairman, a “dingo” when Wheeler was thought to be pushing for a weaker policy.

Under political pressure, though, Wheeler ultimately took a huge step toward “strong” net neutrality by deciding to regulate Internet providers using Title II of the Communications Act. Doing this gave him the power to impose blanket bans on the blocking and slowing of websites, and to force cellphone carriers to obey net neutrality, too.

Why does Pai oppose Title II?

He’s criticized Wheeler’s decision to use Title II as an example of government overreach, and a solution in search of a problem. Many other conservatives also objected to the move, saying it went too far and abused the FCC’s powers. A federal court later upheld Wheeler’s rules in spite of a lawsuit by Internet providers to have the regulations overturned.

So if not Title II, then what does Pai have in mind when he says he’s for “an open Internet”?

Right now, the latest evidence we have is his commitment to a number of other, general ideas about what makes up net neutrality. Speaking to reporters Tuesday, Pai said he was supportive of a number of so-called freedoms identified by former FCC chairman Michael Powell. In the mid-2000s, Powell, also a Republican, laid out what he called “four freedoms” for Internet users that would help kickstart the debate on net neutrality.

First, Powell said, consumers should have the freedom to access their choice of legal content. Second, consumers should be free to run whatever apps they’d like that run on the Internet. Third, they should be able to connect any device to the Internet through the connections they’ve purchased. And fourth, they should be able to get “meaningful information” about the Internet plans they’ve bought.

Now that he’s chairman, Pai isn’t saying much about net neutrality beyond that. But we can look to other Title II opponents for clues as to possible alternatives to the current policy.

Okay, such as who?

Early on in Wheeler’s policy process, some Internet providers and market-oriented think tanks said there was no need to “reclassify” broadband under Title II. Instead, they said, you could keep broadband regulated under a different part of the Communications Act known as Title I – and everything would be fine.

Unlike Title II, Title I represents a lighter regulatory approach that doesn’t allow the FCC to impose blanket bans on certain types of activity. Consumer advocates didn’t like that, saying it would still allow Internet providers to abuse consumers and other businesses. But in theory, one of the things the FCC could do is reverse Wheeler’s decision to use Title II – and go back to regulating Internet providers under Title I. This would potentially mean a more limited form of net neutrality.

Some U.S. lawmakers are in favor of circumventing all this complexity just by drawing up a bill in Congress that settles the debate once and for all. Sen. John Thune, R-S.D., has said in recent weeks he’s still committed to finding a bipartisan compromise.

Could that really happen?

It’s hard to say. Before the election, Democrats had little incentive to work on a net neutrality bill with Republicans because they expected Hillary Clinton to uphold the FCC’s regulation, and some worried that a bill would water down the protections. Now, facing the possibility of a weakened net neutrality, Democrats may be more willing to come to the table, some analysts predict. But Thune’s initial proposal back in 2015 was a non-starter for liberals, because while it enshrined the FCC’s blanket bans against blocking and throttling into law, critics said it also sought to strip the FCC of the power to regulate Internet providers under Title II in the future.

Where does that leave us?

There are several main paths forward, it seems, and any mixture of them seems possible. The FCC could choose not to enforce the net neutrality rules. It could actively seek to roll them back by reversing Wheeler’s reclassification. And Congress could seek to legislate.

It’s unclear which of those things will happen next, but we’ll be watching closely.