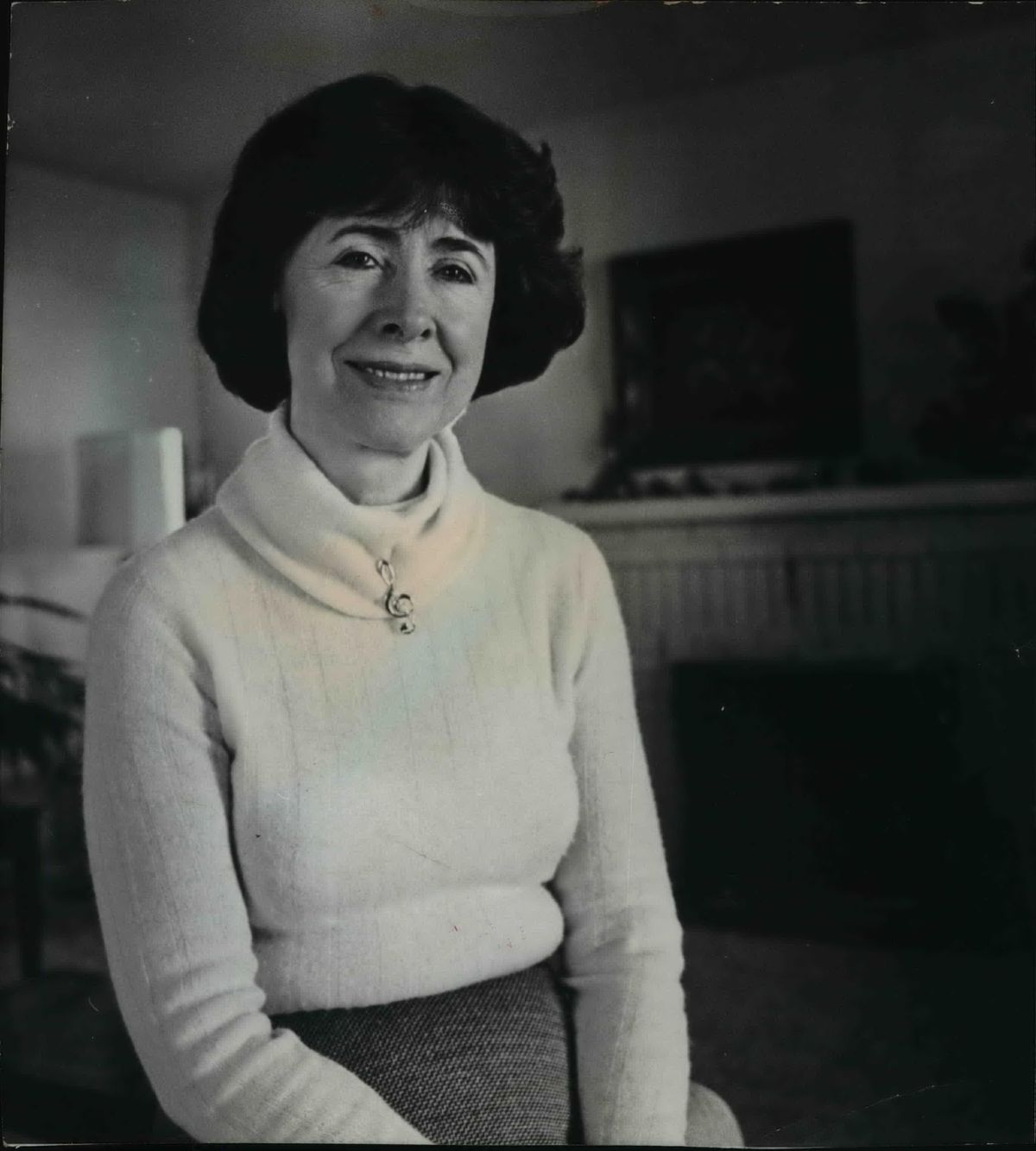

Getting There: Margaret Hurley forced state to take alternate route for north Spokane freeway

The first piece of paved highway in Spokane County was a one and a half mile strip of Sunset Blvd. in 1911. Fifty years later quite a bit more was added with the construction of I-90 freeway from Sunset Hill in March of 1963. (SR)

This is the second part of a two-part Getting There about former state legislator Margaret Hurley. Read the first article.

In 1970, Margaret Hurley was heading toward her 10th term in the Legislature representing central Spokane.

The woman who had been referred to as Mrs. Joseph Hurley had stepped away from his shadow to become something of a firebrand. With a bouffant hairdo and a predilection to do as she pleased, she’d annoyed her own Democratic Party leaders and rebuffed the GOP.

And since her early years as a legislator, she’d kept up a steady drumbeat against urban freeways, despite her inability to prevent I-90 from running through the center of Spokane.

For Hurley, the 1970s were a perfect time to gain support in her opposition. During the first half of the decade, her days in the Legislature would be defined by the fight she led to stop the north-south freeway. By then, freeway revolts had gained momentum across the nation, from resistance to the elevated Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco to the Massachusetts governor stopping construction of the inner belt of highways in Boston.

When the state highway department released the Spokane Metropolitan Area Transportation Study in 1970, which included the “Corridor Study for North Spokane and North Suburban Area Freeway,” Hurley had been introducing bills against such a plan for 15 years.

“I started introducing my ‘pesticating’ bills, you see, in ’55,” she told an interviewer with the state’s oral history program in 1995. “I was always the subject of mild ridicule – snide remarks. In fact one of the department members did say, ‘Well, this little lady ought to be home tending to her kitchen instead of trying to tell the engineers how to do their job.’ ”

A few months after the study was released, Hurley helped form the Citizens Against Residential Freeways with Connie Wise O’Neill, who like Hurley years before, was referred to as Mrs. John O’Neill in newspaper reports. The group held a rally against the freeway at Gonzaga University in September 1970. About 700 people showed up, including Democratic U.S. Rep. Tom Foley, who said he shared their “deep concern” but had no power to influence the state transportation department.

A month later, the group delivered 5,000 signatures to the city. A revolt was afoot, but the City Council was unmoved.

“I would talk to them, and I’d say, ‘It just doesn’t seem right that you would want to destroy the environment of one of the best residential areas that we have within walking distance of downtown, while other cities are trying to repair the damage that is done theirs by urban sprawl. But you are bent on creating it,’” she said. “But like most government agencies, they thought they were God Almighty and they didn’t listen. Didn’t ever listen.”

One member listened, but not at first.

Margaret Leonard was elected in 1969, the first woman in the city’s history to be elected to the city council, defeating the man who would later become the first African-American mayor of the city, James Chase. Her defiance as a citizen against powerful interests in the city, specifically against an urban renewal plan put forth by a business group called Spokane Unlimited, built a political base that she would use later.

The Spokesman-Review wrote an article about Leonard’s first day at City Hall. Headlined “New Council Member Quiet,” it began, “Smiling and wearing a bright red dress (Leonard) told newsmen … that she had come ‘to listen and learn.’ ” After looking at the meeting agenda in her new office, Leonard, “as is a woman’s prerogative, entered the council board room a few minutes after most members were seated. To a man, everyone rose, exchanged small greeting pleasantries, and then were seated.”

Like Hurley, Leonard wouldn’t stay quiet long. About a year after the citizen’s group was formed, Leonard announced her opposition to the freeway.

“As long as there are other alternatives, it seems to me we shouldn’t go through a heavily populated area,” she said, according to a June 28, 1971 article. Leonard would become an important ally in the fight to Hurley, but at first she was alone on the council in her opposition.

As resistance to the freeway grew, Hurley kept voicing strong opposition from her position of power. On the state House floor, she tore into highway planners, calling them “devious, domineering and arrogant.” She introduced a bill that would have required all freeway plans to be reviewed by the Department of Ecology to assess their impacts to air quality and pollution.

Instead of seeing a vote on her bill, Hurley found that the transportation department had substituted its own bill, gutting her original bill. She took legislative action to counter the move, only to find another substitute bill in place of hers.

Fed up with the game, Hurley wrote a formal “remonstrance,” or public rebuke, against the transportation department. In it, she said the transportation department had “arrogant and scornful regard” for the people’s representatives, and accused the department of “consuming huge sums of tax money, rooting up whole communities and covering them with concrete and asphalt.”

The parliamentary maneuver was in the books but no one could remember it ever having been used. And it worked. After the remonstrance, she pushed through her law requiring an environmental review of every state highway project.

“It went on forever,” Hurley said of her fight against the freeway. “It went on practically my whole legislative life – until we passed that bill, which pretty much shut it up.”

In Spokane, Leonard kept the pressure on as well. By November 1973, all four challengers to city council incumbents were opposed to the north-south freeway. Mayor David Rodgers was a strong proponent of the road, saying the city was already “choking on its traffic.”

Leonard was the only incumbent to oppose the road, saying, “I believe there are better alternatives than sweeping out anywhere from 600 to 900 homes to accomplish it. What we need to do is solve the traffic problem now – not 10 or 20 years from now.”

The two Margarets, as they’re still called by some people in the Washington State Department of Transportation, had effectively killed the highway.

Hurley’s law didn’t specifically stop the freeway, but it did delay it. And Leonard’s refusal to bend to Spokane’s powerful business interests helped spur local opposition to the roadway.

“And the costs of the freeway kept going up, and up, and up, and up, until you couldn’t even think of building the freeway,” Hurley said in 1995. “And so we just sat back and rejoiced, because time was on our side.”

She was mostly right. The state transportation department formally abandoned the route up the Hamilton-Nevada corridor in 1991.

“We had an overwhelming response from the public and that was, ‘We don’t like that corridor being considered for a freeway,” Jerry Lenzi, district administrator for the department, said then. “This shows government is responsive to the wishes of the people.”

Dennis Dellwo, who held Hurley’s seat then, scoffed at Lenzi’s remark, noting that freeway planners had “just recognized that there are insurmountable problems and opposition that they should have seen 35 years ago.”

Now, of course, the north-south freeway is on schedule to be completed in 2029. The original price tag of $13 million has ballooned to nearly $1.5 billion. The 600 homes in the Logan neighborhood were saved, but the current route will raze 500 homes and 115 businesses when all’s said and done.

One wonders what Hurley, who died in 2015 just days shy of her 106th birthday, would think. But 20 years ago, she was pleased.

“I got pegged, or tagged, with the stigma of being against freeways, and I had to keep repeating, ‘I am not against freeways. I am only against where you’re locating freeways,’ ” she said. “If they’re going to be so stupid as to try to bulldoze out 650 homes and destroy an area of education and retirement homes and city parks and things like that, they need to have somebody come in and tell them what to do. Even if it’s a woman that comes out of her kitchen.”