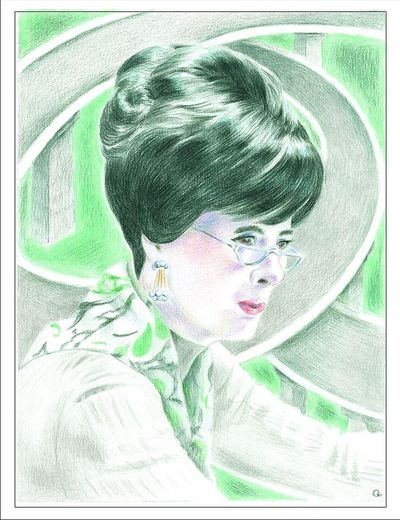

Getting There: The woman who fought freeways

When voters elected Margaret Hurley to the Washington state Legislature in 1952, her desk nameplate read, “Mrs. Joseph E. Hurley.”

Ballots identified her the same. So did the newspapers.

During the following decades in which she represented central Spokane, both in the House and the Senate, Hurley made a name for herself. She was a Democrat who opposed new taxes and demanded the state live within its means. She bucked party leadership on many occasions, and was asked to join the GOP. She declined the invitation.

“I’m not the kind to shut up because some people think I should be a good girl,” she said years later in an interview with the Washington State Oral History Program. “It was the working men and women and their families who were my main concern, and their health and safety. … I didn’t for a single minute consider becoming a Republican.”

Though her name has faded from Spokane’s collective memory since she left elective politics in 1984, her effort is clearly on display on the east side of town. If something that never happened could be named after someone, the never-built north-south freeway would surely carry Hurley’s name.

That’s because the freeway would’ve been built in the 1970s, but Hurley almost single-handedly stopped it.

Now, of course, the north-south freeway is on schedule to be completed in 2029. The original price tag of $13 million has ballooned to nearly $1.5 billion. But the North Spokane Corridor, as it’s now called, was first envisioned in 1946 as a way to ferry the growing ranks of motorists from the city core to the swelling northern suburbs. It wasn’t part of the federal highway system, as Interstate 90 was, but even as the interstate was being constructed, state highway planners said the time had come for a north-south route with six lanes.

Hurley wasn’t a fan.

In the oral history, Hurley said she opposed the north-south freeway from the beginning because it was proposed to go up the Nevada-Hamilton corridor, blazing a route through the densely populated Logan neighborhood near Gonzaga University.

But while the north-south freeway was her white whale, her first reported opposition to freeways came against I-90.

In 1958, the interstate was hurriedly being constructed across the continent thanks to President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956. At the time, most people viewed highways as a “technological and social triumph,” according to Tom Lewis in his book, “Divided Highways.”

“The magic word coined to make traffic problems disappear is ‘freeway,’ ” read a Spokesman-Review article from Oct. 19, 1958. “So you have vehicular growing pains and need a freeway. Where would you put it?”

Ask a question like that, and opinions fly. As the article noted, rumors were rife on where the road would go. One had it tunneling under the South Hill.

As the pavement of I-90 approached Spokane from the east and west, its route through Spokane proper was still undecided, but four possibilities were floated. One traversed the South Hill on Sixth Avenue. Another blazed through Browne’s Addition to find its way to the river’s edge, where it would skirt downtown along Trent, now called Spokane Falls Boulevard.

The clamor for the highway was loud, but the final route still didn’t please everyone. A public hearing on the proposed routes was held at the Spokane Coliseum in 1958, drawing 500 people. Hurley attended, and didn’t like any of the options. The state representative pushed planners to build the highway around the city, not through it.

“We are afraid that a freeway that will rush traffic as fast as possible from Seattle to the Idaho border will not only do us economic damage but will ruin our beautiful city and cause a serious smog situation by 1975,” she said at the meeting, according to an article in the Spokesman-Review.

The state’s top engineer on the project, Donald Stein, dismissed those concerns, saying that a survey showed that “people want to go to and through Spokane – not around it.”

Led by geography, among other more questionable factors like the values of the homes and lack of political power of residents along the proposed route, planners put the highway at the foot of the South Hill.

As she maintained throughout the years, Hurley didn’t oppose all highways. She was against highways plowing through neighborhoods, as I-90 would do, most severely and despite Hurley’s objections, through the poor, powerless neighborhood of East Central.

With I-90 complete, state highway planners planned the north-south freeway through the east Spokane neighborhood, noting that an interchange with the interstate “will virtually eliminate Liberty Park.”

Hurley was incensed. In 1964, as word of the freeway continued to circulate around town, she demanded to know more.

“We want to know why everything about the proposed north-south freeway is so hush-hush,” Hurley said to a reporter that year.

No solid answers came until 1970, when the state highway department released the Spokane Metropolitan Area Transportation Study, a report that had been promised for three years. The SMATS map laid the roadway exactly where Hurley feared: in her own neighborhood, where more than 600 homes stood in its way, not to mention parks, schools and churches.

The Chronicle reported that the report drew “little fire” and quoted City Councilwoman Margaret Leonard as saying the freeway would be “terrific.” She added, “As to location, I think the engineers know better than I where it should be.”

Hurley disagreed. She urged planners to find a route that didn’t traverse through the populated area and instead went around town.

“These issues are more valuable to our way of life than rights of gasoline taxpayers who, to proceed in a straight line from one point to another, would destroy these socio-economic values,” she said.

Hurley’s lonesome fire eventually sparked a movement, one that had thousands of supporters, including city council’s Margaret Leonard. The opposition Hurley had to I-90 in the 1950s finally found its mark two decades later.