Dorothy Powers: All who met life’s joys at the Davenport Hotel mourned its closure

(This article first appeared on June 27, 1985.)

This column is not for the “greats.”

It’s not for the presidents, statesmen, entertainers and heads of foreign governments who have stayed at the world-famous Davenport Hotel in downtown Spokane.

Rather, it’s for those of us here in Spokane who have lived with the grande dame of our hotels all these years and who will feel nostalgic sadness when her heart stops this weekend.

Hotel officials confirmed Wednesday that all food service will end once Sunday dinner is served; the last toasts will be drunk in the bar by midnight Saturday.

No more room reservations will be accepted; some rooms will remain available on a walk-in basis only.

Those of us who have known the Davenport a long time – she’s been here since 1914 – acknowledge that her ancestors were humble, but we admire her all the more for it.

They included a tent named Davenport’s Waffle Foundry, erected after the great fire of 1889, and the Davenport Restaurant, built in 1890.

Every Spokanite cherishes his or her personal memories of the Davenport.

We swirled through its lobby in elegant, full-skirted evening gowns at annual formal balls and stayed to eat scrambled eggs for breakfast in the coffee shop.

Men in tails or tuxedos or dress military uniforms escorted women to formal dinners in elegant dining rooms at tables set with heavy sterling silver flatware, silver serving dishes and priceless china.

Some of us courted over its sterling silver casseroles filled with spaghetti.

They cost only 50 cents.

That was in 1943 – and the whole world seemed young and single then.

World War II filled Spokane with thousands of handsome young servicemen in uniform, and the world-famous Davenport Hotel stayed open all night.

Its coffee shop clearly was “the” place to go after dances and movies.

By the hundreds, very late every night, we ordered either the famous onion soup or a cheese-covered ton of spaghetti served in sterling; we called to each other from table to table.

Then, fed, dozens of young B-17 pilots took their dates home, drove speedily to their base and flew practice missions starting at 3 and 4 a.m. from Geiger Field.

Spokane’s society dowagers knew the Davenport as the place where they met for tea in the lobby and up on the mezzanine that overlooked the lobby’s fountain.

Hundreds of singing canaries in elegantly carved cages graced the arches in the lobby; a bird caretaker saw to their health and their daily cleaning.

In the basement, a genial fellow equipped with special solutions and a burnishing machine “washed” all the silver coins to be given in change to Davenport patrons.

By the time “Silver John” Ungari died on Dec. 17, 1973 he was said to have cleaned more than $51 million during the 55 years he worked for the Davenport.

The gleaming silver dollars became a trademark of the Davenport; in most parts of the country, anyone who pulled such polished coins from his pockets could expect to hear: “You must have been at the Davenport in Spokane.”

Every Easter season, the Davenport lobby was turned into a giant garden, ablaze with masses of blooms.

Whether you dined there or not, you made it a point to “go look.”

And for all of us, there were two significant landmarks in the lobby – the fireplace where, for years, the fire was not allowed to go out, and the fountain, sometimes filled with goldfish and then other times used as a huge epergne filled with flowers.

There – at one spot or the other – we met our friends before going to dinner or the downtown theatres.

But this weekend, the Davenport Hotel will have many mourners.

Prominent among them will be Spokane attorney Paul F. Schedler.

He recalls being taken to dinner in the fashionable and elegant Italian Gardens dining room in 1925 by an uncle, Paul Shallenberger of Portland.

“In the late 1920s – I was still a student at Lewis and Clark High School – I was invited to play saxophone in Mel Butler’s orchestra during the dinner hour; I guess I filled in for about two weeks while an orchestra member was missing,” Schedler said.

“We played nice, soft music during dinner, and in the middle of the dining room, there was a space for dancing.

“After Butler’s orchestra left, another orchestra known as the Mann Brothers played there.

“I also had my own five-piece band; we played for churches, and there wasn’t a Grange hall within 150 miles where we didn’t play.

“My dad let me borrow his four-cylinder Whippet, and here we five kids would go – with a bass drum and all the other instruments – in that tiny car.

“After every out-of-town performance, we’d go to the Davenport coffee shop for chicken gumbo soup.

“The chef was Henry Mathieu, and he wouldn’t tell anybody in the world his recipe.”

Shedler also recalls that Western author Zane Gray “holed up in the Davenport to write a book about an Inland Empire wheat town titled ‘Desert of Wheat.’

The attorney remembers that “my mother’s nephew, a great fisherman, once caught a whole bucketful of rainbow trout and donated them to be placed in the pool around the lobby fountain.

“It was winter, and they proved to be quite an attraction, but by spring, there was only one left.”

The Davenport occupies a special space in all our hearts in this town.

There, we’ve laughed, talked, dined, danced, honeymooned, bid farewell to young servicemen of four wars.

The goodbye we say to the Davenport this weekend – if it proves to be final – will leave many of us saddened and will rob future Spokanites of a special piece of history.

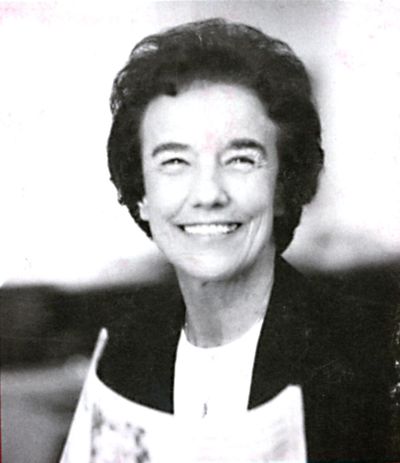

The late Dorothy Powers, winner of numerous journalism awards, worked at The Spokesman-Review from 1943 until her retirement in 1988. She died in 2014 at age 93.