Meth, often mixed with opioids, leads spike in Spokane County drug overdose deaths

Spokane police haven’t busted a methamphetamine lab in at least three years, almost the same amount of time “Breaking Bad” and its meth-cooking protagonist have been off the air. But methamphetamine is contributing to more drug overdose deaths than any other drug in Spokane County, and that number rose significantly in 2016.

That’s according to a Spokane County Medical Examiner’s office report on 2016 deaths released Tuesday, which found an increase from 29 fatal overdoses involving methamphetamine in 2015 to 49 in 2016, a 69 percent jump.

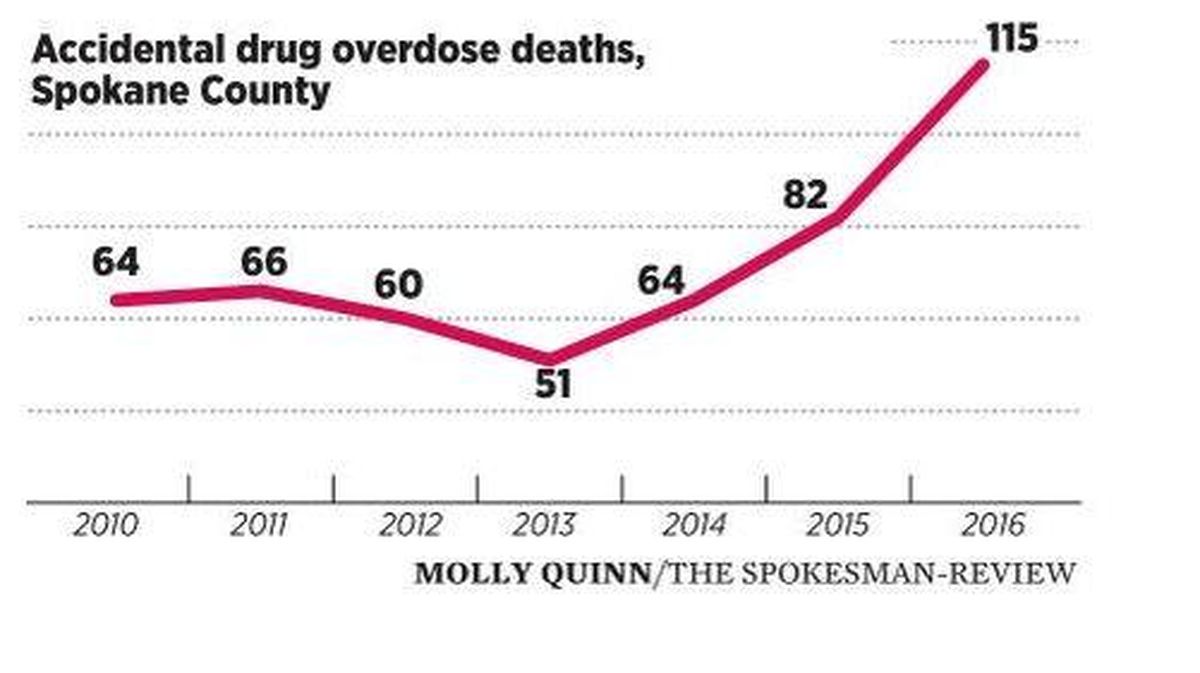

Overall, accidental overdoses in Spokane County rose from 82 in 2015 to 115 last year.

Fatal heroin and opioid overdoses are the usual focus of conversations about drug use and deaths, but methamphetamine is a rarely-discussed contributor to soaring overdose death rates in Washington.

In many cases, public health officials say that’s because people are using opioids in combination with methamphetamine.

Methamphetamine is a stimulant and can cause fatal overdoses by putting strain on their heart or circulatory system. The drug elevates core body temperature and usually kills by cardiac failure.

Fatal overdoses on opioids are more common. Those drugs are depressants that can suppress breathing, leading to fatal respiratory failure.

“When you do both at the same time you compound the effects of both drugs. One doesn’t counteract the other,” said Mike Lopez, medical services manager for the Spokane Fire Department.

The medical examiner report says how many times a drug was listed on death certificates in 2016, but it doesn’t provide a clear picture of how people are using those drugs.

People often overdose and die with more than one drug in their system, so without the details of individual death certificates, it’s impossible to say if most local methamphetamine overdoses also involved an opioid. The medical examiner’s office had not responded to a request to provide more detailed data by Wednesday evening.

A 2015 survey by the University of Washington’s Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute of 22 Spokane needle-exchange users found 91 percent had used meth in the past three months, and nearly one-third had used both methamphetamine and heroin together.

Statewide, it’s clear people are mixing the two. The Washington Department of Health collects data on fatal opioid overdoses, which lists every drug found on individual death certificates.

Though it’s not an opioid, methamphetamine was the second-most commonly listed drug in 2015, contributing to 155 opioid overdoses. In 2010, methamphetamine was present in just 44 opioid overdoses and ranked well behind common painkillers like oxycodone.

Rates of people using only methamphetamine also appear to be going up, said Caleb Banta-Green, the principal research scientist for the institute. Overdose deaths have increased in King County after holding steady for nearly a decade, he said, and that appears to be a trend across the state.

The institute is releasing a report on rising methamphetamine use in Washington in a few weeks.

As public attention has been focused on responding to an opioid overdose epidemic, there’s less talk about methamphetamine.

After a crackdown on the cold medications used to make the drug in the United States, production shifted largely to Mexico.

Use declined for a few years, Banta-Green said. But its gradual increase over the past few years has gone largely unnoticed because it doesn’t come with the dramatic spectacle of police raiding meth labs.

Crackdowns on prescription pain medication over the past decade have made it harder for people addicted to opioids to get drugs legally. In response, drug traffickers used the same routes they set up for methamphetamine to bring more heroin into the country, Banta-Green said.

Treatment programs created in response to soaring opioid overdose deaths often have few options for people who also use methamphetamine, benzodiazepines and other drugs, Banta-Green said. In many cases, providers refuse to treat them at all, “which really means we’re only saying we only want to treat half of heroin users,” he said.

The state health department publishes data on opioid deaths, but not methamphetamine overdoses.

“There’s never been a statewide discussion about it,” Banta-Green said.

This article was updated on April 27, 2017 to clarify that the Washington Department of Health does not publish data on methamphetamine overdoses. The department does collect data on all drug overdoses.