As Spokane AIDS Network closes its doors, clients and staff remember years of community, support

Spokane Regional Health District case manager Jean Doherty, left, talks with Jason Prettyman at Spokane AIDS Network in Spokane. The network recently closed after losing its state contract for services. (Kathy Plonka / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

When Kaleb Ashby found out he was HIV-positive, he thought his life was over.

Ashby was 19 and living in Minnesota with no car. He had to travel 45 minutes to a Centers for Disease Control lab to get his test confirmed. The health worker who told him he was positive gave him nothing: no information about how to reduce his risk of transmitting the virus, nothing about his chances of survival or how treatment drugs might affect him.

“I thought I was going to die,” he said.

Ashby contracted the virus after being raped at 14, he said, and already struggled with trauma. With his new diagnosis, he felt isolated, and thought about killing himself. The nearest support group for people with HIV was over two hours away.

Dejected, Ashby moved to Spokane, where he learned about the Spokane AIDS Network. When he walked in the door and met his new case manager, she gave him a hug.

“She made me feel like I was actually cared for, cared about,” he said.

Ashby, now 25, is among the hundreds of HIV-positive people who have found a community in the network’s roomy house on the Lower South Hill. For about 30 years, the network helped HIV-positive people across Eastern Washington stay current on their medications while receiving food, bus passes, help with housing and other services.

Last month, the AIDS Network closed, shifting all HIV and AIDS care and prevention services to the Spokane Regional Health District.

The two groups have worked together for more than two decades, with the health district providing case management for more than half the area’s patients.

Formed early in the crisis

The first cases of what would later be called AIDS started showing up in San Francisco and New York City in the early 1980s. Before long, thousands of people, many of them gay men, were dying from rare types of cancer, pneumonia and other opportunistic infections that took advantage of the body’s weakened immune system.

It would be several years before researchers isolated the virus causing the illnesses, and more than a decade until HIV-positive people had some hope at longer lifespans thanks to antiretroviral drugs, which came on the market in 1996. Those drugs are now developed enough that many people with HIV can live a normal lifespan.

Groups like the Spokane AIDS Network formed in the early years of the crisis. Though HIV infection is a manageable chronic illness for most people, it still requires a significant amount of care.

Diagnosis can be devastating, especially for people who still think of HIV as a death sentence. People need mental health care, support, and information about managing their condition and not spreading the virus to others.

Dino Lopez was diagnosed in 2007 after his partner failed to tell Lopez he was HIV-positive. The two broke up soon after: Lopez said he forgave his partner, but the guilt was too difficult.

He was living in Moscow, Idaho, where services were minimal, but he was able to meet with network staff to learn how to manage his illness.

“They showed me the ropes,” he said.

Eventually, he moved to Spokane so he could be closer to a community. He’s enthusiastic about helping others get out of the house, and likes to accompany them to the library.

Lopez is blind in one eye, the result of a toxoplasmosis infection. He was hospitalized about a month after his diagnosis when his body reacted poorly to treatment, and said about half of his 12 siblings came to visit him in the hospital. There, he told them he didn’t want them to lie about his diagnosis to family back in Mexico.

“The more people know about your infection, the better,” he said.

The virus mutates over time, so patients have to change drugs to stay on top of it. The cost is significant, even with health insurance. Mark Garrett, a network peer advocate, said the annual cost of his medications is about $60,000. Even with health insurance, co-pays are so high that he, like most HIV-positive people, rely on government funding to make up the difference.

“I don’t think there is any other disease that has demanded so much of the patient,” Garrett said.

For people like Ashby diagnosed after the initial AIDS crisis, the network was a lifeline. Ashby became a prevention specialist for the group, educating people about how HIV is transmitted, safe sex and pre-exposure prophylaxis, a drug regimen that makes HIV-negative people less likely to contract the virus.

They took care of each other

For people who lived through the early years of AIDS and made it out alive, the network remained a place of healing and community.

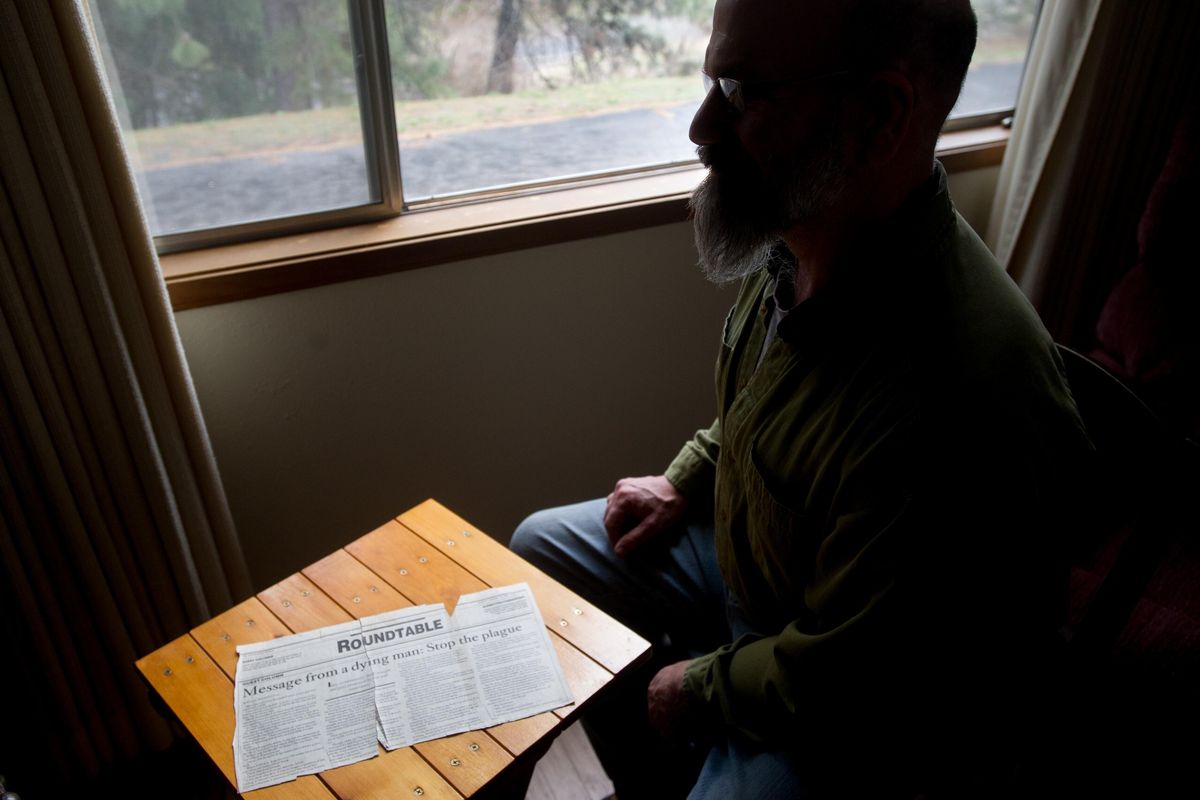

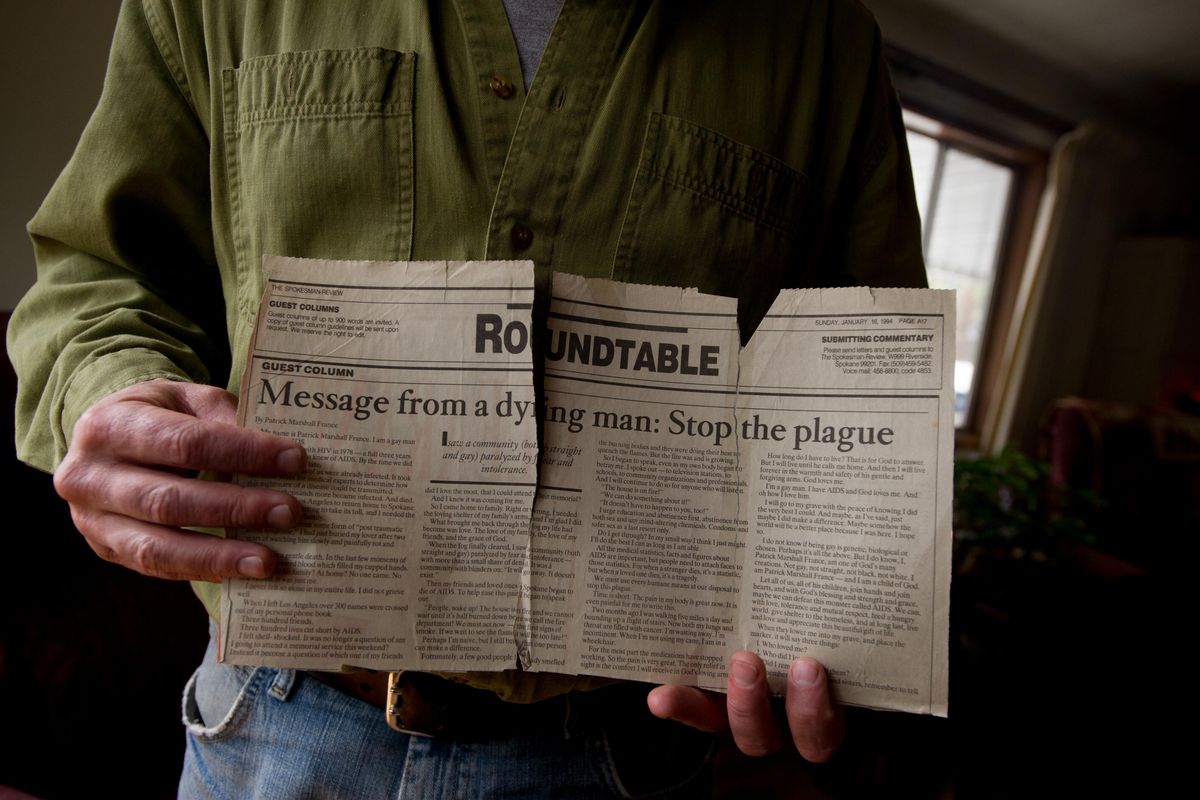

Dale Briese was supposed to die in 1987. He and his partner found out they were HIV-positive on the same day in 1985. Though he was raised to be proactive and fight for what he wanted, Briese struggled after being told he had two years to live.

“I had a death sentence,” he said.

In the first years of the epidemic, many public health districts and government bodies were reluctant to get involved in AIDS. Nobody wanted to talk about gay sex or appear to be condoning it, which made prevention efforts difficult. Medical science was at a loss, so sick people swapped homeopathic remedies and diet advice. Newsletters and flyers were copied, telling people how to cope with symptoms of a weakened immune system.

Many of the gay men who were sick were also estranged from their families, so early AIDS patients had to care for each other. Briese was one of the men who began cooking meals and providing emotional and material support to people who were dying.

“We saw people dying in their homes,” he said. He and others worked “just to get food and some kind of outreach to them … and just to be with our fellow humans when they were suffering.”

By 1987, those informal services were incorporated as the Spokane AIDS Network. Early efforts focused on helping people with end-of-life care and educating people about prevention and safe sex. Advocates and prevention specialists worked with the network and the health district to reach out to other groups affected by the virus.

Sandy Williams was the one-women Spokane office for People of Color Against AIDS Network, a Seattle nonprofit, in the early 1990s. She went home-to-home seeking out black people, many of whom avoided seeking care because they thought of AIDS as a gay white man’s disease.

“The numbers of black women who were being infected was skyrocketing, and our community didn’t want to hear that,” Williams said. Many heterosexual women got infected through male partners.

That remains true today: The rate of new HIV diagnoses for black Washingtonians is nearly eight times the rate for white residents, according to the most recent Department of Health report.

In his first years living with AIDS, Briese drove to San Francisco for much of his medical care on the advice of his Spokane doctor. He remembers waiting in a line with other gay men at San Francisco General Hospital, “waiting for the virus to take my life.”

One of the hardest years for the Spokane community was 1995, Briese said. He went to 15 memorial services in 16 weeks and buried his longtime partner. If those men had made it one more year, they would have had access to life-saving antiretroviral medications.

“It was the hardest death year,” he said, tearing up.

‘A food bank on steroids’

As care for patients and drugs evolved, the AIDS Network expanded its services into medical case management, a food pantry, housing assistance and other support. More than any one service, SAN clients and staff say the house has been a “sanctuary” and “safe haven” for people to gather, ask questions and receive support from others who are living with the same illness.

“It’s a food bank on steroids,” said Garrett.

Washington’s Department of Health typically only funds one HIV/AIDS services provider for each county or region, but has made an exception for Spokane, allowing both providers to operate for more than two decades. The health district served more than half of Spokane’s patients, but SAN provided extra services like food, and operated other offices in Eastern Washington.

That changed last year, when both groups applied for the same contract rather than submitting a joint application. Lisa St. John, the health district’s HIV/AIDS program manager, and Gaye Weiss, the network’s executive director, said neither group brought up the possibility. The health district was awarded the full contract, and the Spokane AIDS Network lost its main source of funding.

The network has shut its doors and is selling the house it has occupied since 1996. Existing clients and some staff shifted to the health district, and the SAN board will remain operational to decide whether it still has a role to play in the community.

St. John said her office has been working to make the transition as smooth as possible. The health district will have an advisory board of HIV-positive clients and has moved a number of Spokane AIDS Network case managers over so clients will have consistency.

Taking input from the network, she also included funding for food vouchers, medical transportation and other services in the health department contract.

“We wanted to make sure all clients have the resources they were used to receiving,” she said. “The goal was to make sure that there were no gaps because of the transition.”

Some clients, like Lopez, are optimistic about the shift. Others are apprehensive, fearing the health district won’t provide the same feeling of community.

Briese worries about HIV being seen primarily as a medical issue, with programs focused on monitoring how much of the virus is in his blood, rather than his well-being as a whole person.

Long-term survivors like him struggle with trauma: the years of attending funeral after funeral, the guilt of improbably living 30 years with a virus that killed friends and boyfriends. For them, HIV is more than a diagnosis. It’s a shared history.

Early AIDS patients developed strategies for managing a chronic illness and supporting each other that are now used by people with cancer, diabetes and other serious illnesses, Briese said.

“HIV has been a big catalyst for understanding diseases like the cancers we have now,” he said.

As he talks about his years with the Spokane AIDS Network, he’s at once emotional and reflective. Spokane is losing something irreplaceable in the network, a history of mutual support and a safe, welcoming space that changed lives, he said. He’s skeptical that could ever be replaced, but hopes the health district can provide a similar environment.

“I think they can learn that,” he said. “I really have faith.”