Washington Supreme Court water-rights ruling will affect building permits for rural property owners

Spokane County officials say a recent water-rights decision by the state Supreme Court will have “dramatic impacts” on property owners looking for building permits in rural areas.

The court on Oct. 6 ruled that Washington counties must make sure there’s enough available water before issuing permits for new developments. The decision primarily affects applicants who rely on so-called “exempt” wells.

Property owners don’t need a permit to draw water from an exempt well as long as they take less than 5,000 gallons a day. But if they want to build a house that relies on that well, they’ll have to prove they won’t infringe on someone else’s water right or violate environmental rules designed to protect fish, the court said in its 6-3 decision.

The lawsuit was filed in 2013 by Futurewise, an environmental group that opposes urban sprawl, and four citizens in Whatcom County.

“The Supreme Court’s common-sense opinion protects both fish and consumers,” said Chris Wierzbicki, Futurewise’s interim director, in a news release. “Fish and wildlife are protected by planning for growth in a way that protects the instream flows needed to maintain their habitats. Consumers are protected because new lots and new homes must have a legal supply of water the buyers can rely on long-term.”

Spokane County officials, however, say the decision shifts a major burden from the state Department of Ecology onto county staff and people wanting building permits.

“The applicant will need to provide an analysis demonstrating that the well does not impair a senior water right, and then we’re going to have to review that analysis,” said Rob Lindsay, the county’s water resources manager. “It’s putting the responsibility of managing these waters of the state on county staff.”

In a statement, Spokane County Commissioner Shelly O’Quinn said the decision “makes it more difficult for anyone seeking a building permit with an exempt well. It ties the hands of our Building and Planning Department because we are mandated to follow the court’s ruling.”

Washington law has long distinguished between the legal and “factual” availability of water – what’s physically in the ground. Before the ruling, it was up to the Department of Ecology to determine whether someone could legally use groundwater, and county planning departments relied on the agency’s assessments when issuing permits.

“Most counties were relying on Ecology to say yes or no,” Lindsay said.

But the court said Washington’s Growth Management Act is clear: Counties are responsible for decisions about land use, and for ensuring that new developments will have an adequate water supply.

Moreover, the court said permit-exempt well users shouldn’t be allowed to take water from a basin that’s otherwise closed – as the Department of Ecology explicitly allowed under a 1985 rule.

Mike Hermanson, a water resources project manager for Spokane County, said it’s difficult to determine whether a development would “impair” water availability for a senior right-holder.

“Impairment is a hard thing to define,” Hermanson said. “The actual definition of impairment is nowhere in the law.”

Randy Vissia, the county’s building and code enforcement director, said he’s not sure if his staff is qualified to make such assessments.

A Department of Ecology spokesperson didn’t return a message seeking comment Tuesday, but the agency’s website says it’s “still unclear” how counties should respond to the decision.

“We are disappointed the Supreme Court did not defer to our interpretation of the water management rule,” the website says. “We’re committed to working closely with county leaders and stakeholder groups to best manage water.”

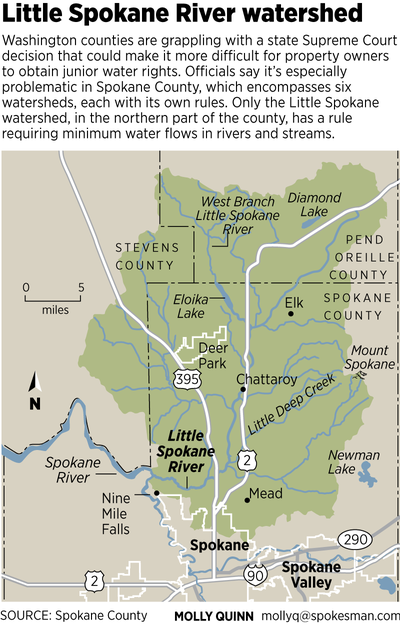

Spokane County encompasses six watersheds, each with its own rules. Of those, only the Little Spokane River watershed, in the northern part of the county, has an instream flow rule setting minimum water flows for rivers and streams to protect fish populations.

Instream flow rules have been regular targets of litigation since their creation in 1976.

Hermanson said those rules “have been litigated a lot, and now it’s been firmly established that they are water rights with a priority date, and they cannot be impaired.”

Officials said the Supreme Court decision adds urgency to the county’s efforts to create a water bank, in which the county would buy water rights and sell them to residents.

“In Spokane County it’s next to impossible to get a new water right,” Hermanson said. “Has been for a while.”

Futurewise and Spokane County recently settled more than a decade of litigation over the county’s Urban Growth Area. The settlement, which also involved several individuals, neighborhood groups and state agencies, prevents the county from expanding the Urban Growth Area until 2025, a move that developers opposed.