TransAmerica Bicycle Trail is ride of a lifetime

Bicyclists ride the Oregon Coast along the TransAmerica Bicycle Trail in 1976, the year the route was unveiled by Missoula-based Bikecentennial. (Rich Landers / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Out of college and entering her first window of uncommitted time, Hillary announced plans to join another young lady for a fall-to-winter bicycle tour across the USA.

“But wouldn’t this be a good time to look for a job?” I suggested, hoping to stimulate conversation about career goals.

“What did you do when you were 24?” she asked, as if she didn’t know the answer.

Realizing Hillary had taken a commanding position in the discussion, I shifted gears by reaching to the frame-mounted lever linked to the Campagnolo Rally of my intuition. Ca-chunk.

We began spinning in the same direction, talking about routes (Southern Tier), maps (Adventure Cycling), a touring bike (her mom’s) followed by ongoing consultations on training, gear, and safety.

Her sister, Brook, had the brilliant idea to bicycle through Spain while pursuing her Spanish degree. Then she joined a girlfriend in the gap between college and work to pedal the Great Parks Route 1,500 miles from Jasper, Alberta, to Durango, Colorado.

Brook boiled her vast experience into a succinct tidbit of advice: “Keep your mind open and your tires pumped up.”

Weeks later, on Hillary’s last shake-down ride, I gave her a “fanny bumper” –a blaze-orange slow-moving vehicle triangle I’d saved nearly four decades as a memento. Hillary thought the “Bikecentennial 1976” logo was cool. She mildly surprised me by promising to wear it.

And then she was off on what I knew would be the ride of her life.

Understanding the value of a long-distance bicycle tour didn’t come to me naturally 40-some years ago. My awakening occurred in the University of Montana Ballroom as I absorbed an evening program about two couples tackling a bicycle tour from Anchorage, Alaska, to the tip of South America.

Greg Siple, who struck me as conspicuously unjockish, recounted the 18,272-mile, two-continent bicycling odyssey he called Hemistour. The stories, photos and Siple’s anyone-can-do-this attitude rewired my mind with the potential for muscle-powered adventure.

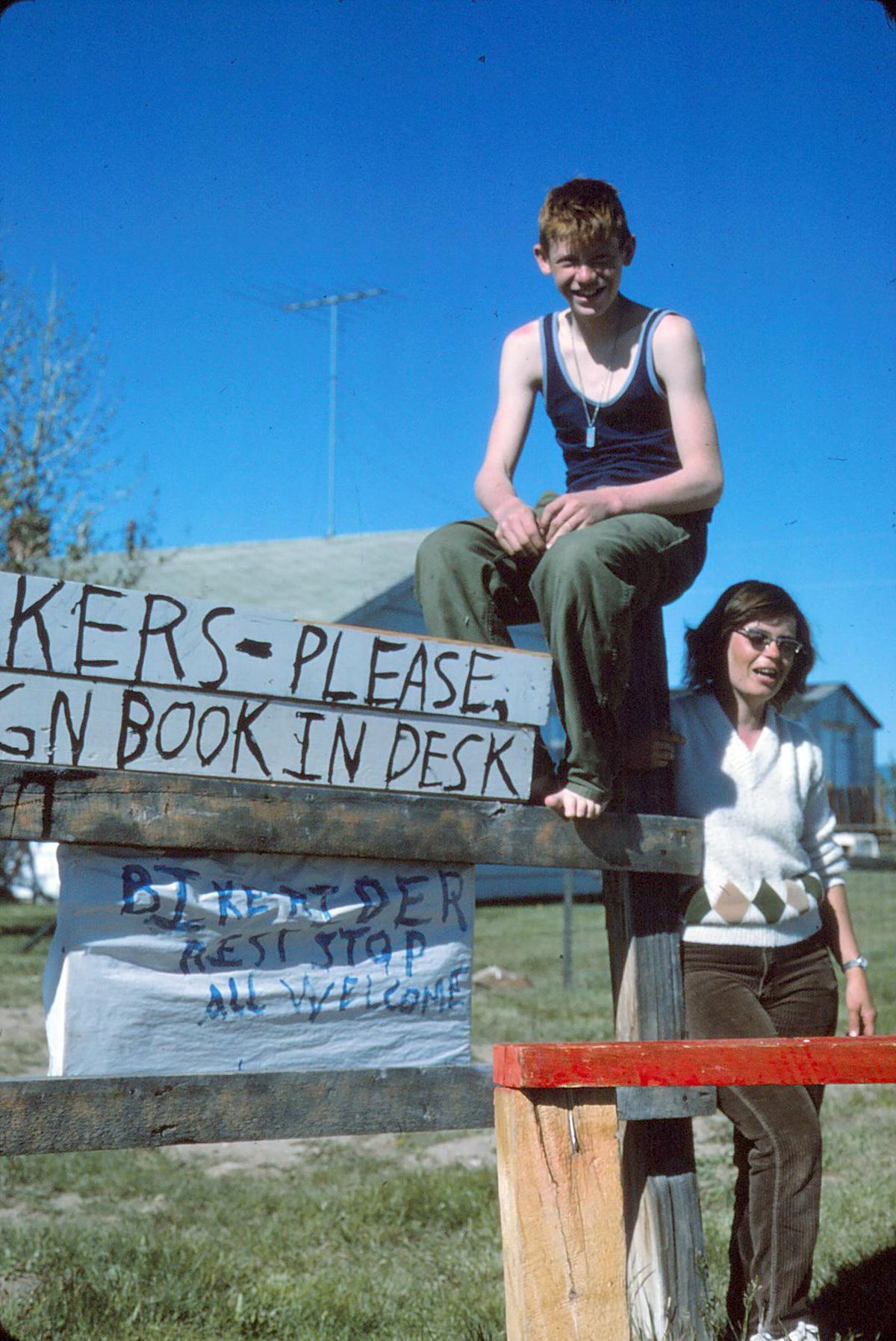

When Siple also mentioned that an operation called Bikecentennial was organizing in Missoula, I tagged onto a wheel behind people with vision. I signed up for leadership training to guide two-wheeling tourists in the inaugural year of the TransAmerica Bicycle Trail.

The pureness of the Bikecentennial mission captured my heart and led me to serve years later on its board as the nonprofit transitioned to Adventure Cycling, which continues to flourish in Missoula.

I could think of nothing more purely beneficial to civilization and the planet than encouraging more people to ride bikes.

But before I served, I indulged. Rather than ushering a single group 4,300 miles from coast to coast in the nation’s Bicentennial year, I was the only B-76 leader to plan five two-week trips in sequence from Oregon to Virginia.

These tours were geared to cyclists who couldn’t commit an entire summer but wanted to sample a section of the Coast-Cascades, Rocky Mountains, Plains-Ozarks, Bluegrass or Appalachian regions.

That schedule allowed me to pedal with the equally engaging independent cyclists during the hundreds of miles between the end of one group trip and the beginning of another. I had the best of both bike touring worlds that summer and savored every mile and acquaintance along the way.

I was a wide-eyed Montanan who knew little about the real world except that I wanted to see it. The bicycle was my vehicle to that end, breaking down barriers like a tank.

My bike was the power that generated the confidence I needed for explaining to one tripper, a physician twice my age, that we were going to enjoy ourselves on a group budget of $5 per person per day. Ten cyclists sharing costs for campgrounds and cooking one-pot meals could tour lavishly on that amount in 1976.

While times have changed in 40 years, the TransAm experience has not. Adventure Cycling has added two more coast-to-coast routes offering the same reward regardless of whether it’s through the north, the heartland or the Southern Tier.

The payoff is the adventure of being on the road long enough for bicycling to become your way of life.

For a young Montanan, it was a graduate degree in American Culture. I played my first game of basketball with African-Americans, took my first walk through tobacco fields and sampled the lips of a pretty girl with a southern accent.

The TransAmerica Trail became my community. The day I rode into Ash Grove, Missouri, a Bikecentennial rider was killed in an accident with a motorist. The flag in the city park was at half mast that night and a local minister had scheduled a prayer breakfast. Townsfolk were in shock and they needed us to know that.

Some bikers rode on, but a few of us stayed. That was the first time I was compelled to attend a memorial for someone I didn’t know.

Reaping the rewards of a coast-to-coast ride is all about determination, spirit, and especially about pace – a discipline you must acquire like a taste for dark beer.

Even though I’d already pedaled a thousand miles on the TransAm Trail before I met my second group in Missoula, I was about to be served one of my most important touring lessons. The teacher was Margaret Jones, 58, a silver-haired conspicuously unathletic adventurer from Washington, D.C.

Our two-week tour into Yellowstone Country began on a dusty, mostly gravel detour route. The day of tough riding left three strong men in the group visibly shaken while Margaret came to camp slightly behind us but fresh as a wildflower. She had a contagious curiosity that soon had all of us parking our bikes numerous times each day to hike a trail, socialize with locals, or explore the ruins of homestead cabins.

She also packed a washcloth for a nightly ritual to freshen her body and her attitude, even when the only available water came from a campground spigot.

Margaret taught us to look at each day not in terms of the destination, but as an enriching journey.

By the time I reached Pueblo, Colorado., I had made the transition from the Rockies to the Plains. My attention began to focus less on the scenery and more on the people.

I sometimes stopped and had chats with three or four farmers or townsfolk a day. Riding to Houston, Missouri, I noticed more people sitting out the heat on their porches. The dogs would not come out of the shade to chase me.

By the time I reached Falls of the Rough, Kentucky, I had developed a taste for corn muffins, grits and chess pie. Within a few days I visited a Trappist monastery, a bourbon distillery and Monticello. I noted in my journal, “What a country!”

I detoured from the TransAm Trail in the final weeks of my two-wheeling summer to avoid the tendency to be obsessed with finishing. The foreign country they call The South offered so much more to discover.

I reveled in the Old Time Fiddlers Convention in Galax, Virginia, before hiking a stretch of the Appalachian Trail, where a family offered to share their campsite. I serenaded their young children to sleep with my harmonica, soothing any urges I’d had to rush on.

The Republican National Convention was voting the night I met with my last group for the two-week tour to Yorktown. Either Ford or Reagan would have envied being part of a grass roots group that clicked so smoothly as we traveled the Blue Ridge Parkway and mingled with the salt of the earth.

After 40 years, I don’t think much about the rain, snow, hills, heat and headwinds that tried to consume my attention in the summer of ’76. My daughter doesn’t dwell on touring hardships, either – although she argues that the TransAmTrail headwinds near Jeffery City, Wyoming, are a breeze compared with the Santa Ana winds she endured out of California.

But if you ask about Hillary’s tour, her memories, like mine, boil down mostly to the ride, the trail and the people who opened our eyes to America.