Diving for his life: Colin Zeng seeks U.S. citizenship

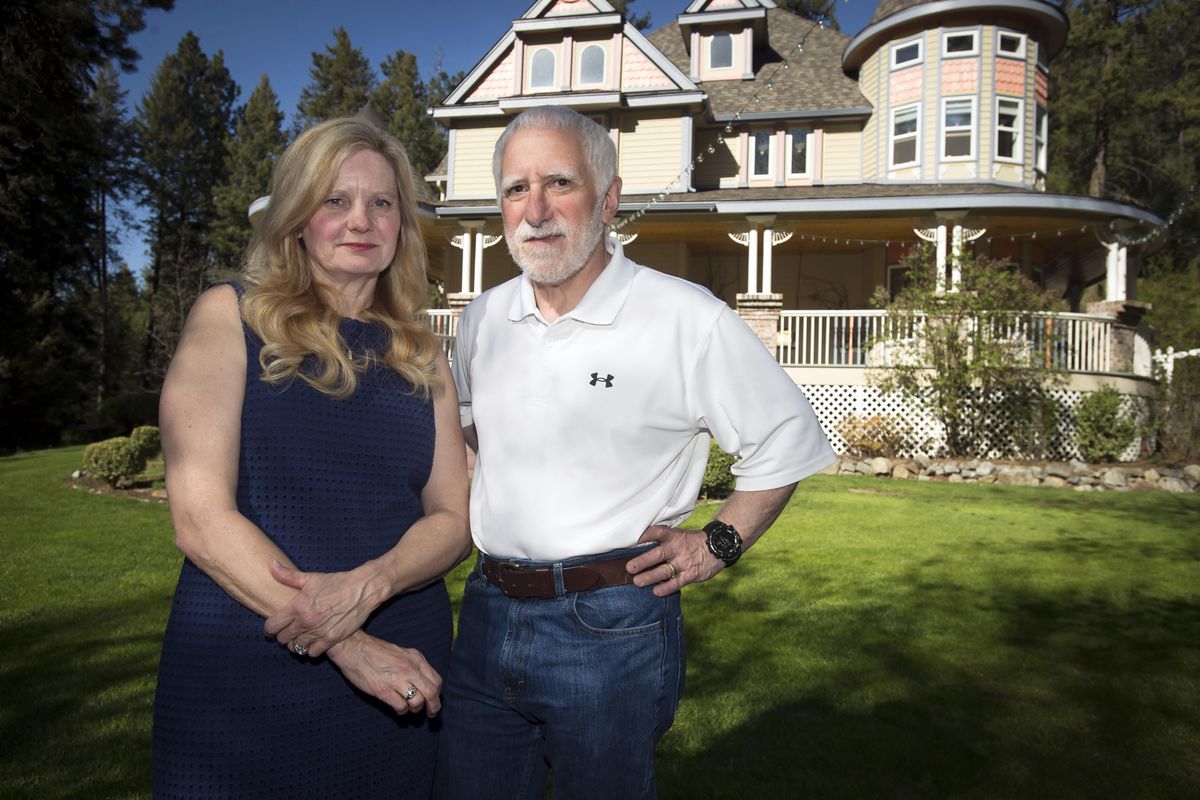

Jolyn and Earle Canty are the guardians of NCAA champion platform diver Colin Zeng, whose Chinese family sent him to the United States for educational and athletic opportunities. (Colin Mulvany / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Justin Sochor, head men’s and women’s diving coach at Ohio State University, worried.

“He wouldn’t be allowed to dive if they couldn’t stop the bleeding,” he said.

In the stands, Zeng’s “American Mom,” Jolyn Canty, of Spokane Valley, prayed for a miracle.

So did the young man from Fujian, China, whom she and her husband, Earle, had taken into their home six years ago.

“I was praying,” Zeng said. “I was asking God for help. I’d trained so hard for this.”

His nosebleed temporarily staunched, he mounted the platform.

“He needed a perfect dive,” Sochor said.

But nearly perfect proved good enough. Zeng executed a nearly flawless dive, nailing the front 3 1/2 pike, scoring a 90.00. That gave him a final score of 499.10, enough to overcome Quintero and secure the NCAA men’s platform diving championship, making him the first Ohio State diver to win a national championship since 2008.

“He crushed it,” Sochor said. “It was a fantastic dive.”

“I was determined. I didn’t hold anything back,” Zeng said.

Now, he’s praying for another miracle – U.S. citizenship and a chance to earn Olympic gold.

China

According to China’s one-child policy, still in effect when he was born, Zeng shouldn’t even be here at all. He’s the third-born child of a poor family. When his mother was 8 1/2 months pregnant, the government sent a medical official to perform a forced abortion. His mother fled and jumped from a small balcony. The fall induced labor and his parents and two sisters welcomed the new baby with joy. His family was forced to pay a heavy fine for defying the one-child policy.

Since only the firstborn child is allowed an education, Zeng’s parents searched for a way to provide one for him. They found the answer in diving.

At 7 1/2 he was evaluated by the village doctor and identified as being physically suited to diving. In China, it’s a great honor if a child from one’s village is chosen to go to Beijing to train as a diver, and his parents were told that if they allowed their son to go to Beijing he would also be allowed to attend school.

“My parents sent me to Beijing for a diving trial at Tsinghua University, which lasted three months,” Zeng said. “I remember when the coaches showed us the 10-meter diving platform. It was so scary. I looked down and I couldn’t even breathe.”

He hastened to add that his first dives were strictly poolside.

At the end of the trial, Zeng was accepted into the program. His parents were relieved that he would get the education and opportunities usually reserved for firstborn children.

“The program was tough,” Zeng said. “I lived with teammates and coaches. From Monday through Friday, we got up at 6 a.m. and practiced till 7. At 8 a.m. we went to school.”

School ended at noon and then they had diving practice from 1:30 to 7 p.m.

He kept that grueling schedule, including Saturday and Sunday practice, for several years.

His talent was noticed and at age 11 he was moved to the men’s Olympic training program. At the Olympic level, athletes are not allowed to attend school.

This upset his mother. Her sole reason for allowing her son to move to Beijing was so that he could have the education previously denied him. When she asked that he be allowed to attend school, Zeng was summarily dropped from the program. He was forced out of the dorm with no food, no money and nowhere to go.

“I lived on the street for a few days,” he said.

A mother of another diver in the program found him huddled in a drainpipe by the diving facility. She notified his family and took him in.

In 2010, she was able to get a visitor visa for Zeng to come to the U.S. with her daughter, also a diver, to attend training camp at Stanford University.

From Stanford to family

At Stanford, Zeng met Ethan Canty, a meeting that forever changed his life. The Cantys were living in Sunnyvale, California, at the time.

“Ethan came home with the story of a talented Chinese diver,” Jolyn Canty said. “He said, ‘You’ve got to save him.’ ”

His faith in his parents’ ability to help wasn’t misplaced. They’d already adopted his brother, Sam, from a Romanian orphanage, and his brother, Timothy, had been abandoned at Sacred Heart Medical Center as an infant. The Cantys took Tim in as a foster child and eventually adopted him.

“When we heard Colin’s story, we knew we needed to do something,” Canty said.

They were able to contact Zeng’s parents and offered to have him move in with their family and attend school.

“They were overjoyed and wanted this opportunity for Colin very much,” Canty said. “We became his guardians and contacted Ethan’s school, The King’s Academy. The school agreed to seek a student visa and provide a full scholarship for five years.”

Zeng thrived in his new home, but there were some bumps along the way. He didn’t speak any English and wasn’t used to living with a family. He’d lived with teammates and coaches for most of his childhood.

He was amazed by the way the Cantys welcomed him.

“It’s hard to find a family who’s willing to do that for a total stranger,” he said. “But they took me in and now they are always there for me.”

Zeng continued to excel at diving. According to DiveMeets, he finished first in all of the competitions he competed in during high school. He worked hard to learn English, and graduated in 2014 with a high GPA, and was high school All-American for four years and All-American national champion for two of those years.

He also discovered the Christian faith.

“They (the Cantys) challenged me to be a man of God,” he said. “My faith is the most important thing to me.”

Ohio State

It’s no surprise that Zeng was sought after by diving coaches at universities nationwide.

His work ethic and accomplishments brought him to the attention of Sochor, who took over the Ohio State diving program in 2013.

“I’m only the fourth coach in the 90-year program at Ohio State,” he said.

Sochor inherited a team laden with juniors and seniors and was tasked with shaping a new team. Zeng was just the kind of diver he was looking for.

“He had discipline, high grades and tremendous faith,” Sochor said.

After meeting Sochor, Zeng was convinced Ohio State was the place for him.

“Justin is a very unique coach,” Zeng said. “He’s not so serious.”

Then he laughed. “I’m pretty serious.”

Zeng received a five-year, full-ride scholarship to OSU, and it’s proved to be a good fit.

“We redshirted him his freshman year and used that time to build muscle,” Sochor said. “Colin is the most honest, hardworking, talented and kind human being that I have worked with in almost 20 years as a diving coach.”

After placing first in 24 of 30 events in which he competed, winning two Big Ten championships and sweeping the NCAA Zone C meet, Zeng ended his season on the highest possible note – by becoming a national champion. In addition, he was named 2016 Big Ten Diver of the Year – the only Big Ten award winner to receive this honor unanimously and the first to do that since 2011.

But equally important to Sochor is what Zeng offers as a coach.

“Colin has taken a coaching position with the Ohio State Diving Club, which is an age-group diving club designed to develop divers from their first flip to national and international success,” Sochor said. “Colin is one of the most knowledgeable young coaches that the team has ever had. Not only can he teach and inspire young athletes to be great divers, but he also inspires them to be great people.”

Sochor should know. He was the founder and head coach of that program.

Citizenship and Rio Olympics

And now the dreams of Olympic medals dangle tantalizingly just out of reach.

Out of reach because in order to try out for the Olympic team, Zeng must be a U.S. citizen by June 18. He cannot compete on a student visa.

“Unless something is done, Colin will be forced to return to China when he finishes at Ohio State,” Jolyn Canty said. “The current immigration laws do not allow him to stay in the U.S. and apply for citizenship.”

Zeng’s return to China is unthinkable for his American family.

“Becoming a citizen would save him from unknown and potentially very serious consequences if he returns to China,” Canty said. “We were told that he must never return because the government is very unhappy that he is diving here.”

The Cantys are doing everything they can to ensure his citizenship, including reaching out to legislators in Washington and Ohio. But the path to citizenship is fraught with complications.

Congresswoman Cathy McMorris Rodgers’ office recently released this statement:

“Congresswoman McMorris Rodgers’ office has been working with the Canty family to help facilitate a solution to Colin’s situation, including corresponding with the office of an Ohio representative, where he lives. We are exploring all available options.”

Canty was told one of those options is for a member of Congress to sponsor a private bill for immediate citizenship. She was also told the odds of this happening are extremely slim.

On Friday after waiting a month for reply, Canty received a call from Sarah Monteith, Senator Patty Murray’s Immigration Constituent Services and Outreach Representative.

“I was told Sentator Murray has decided not to pursue helping Colin with a private (bill) in Congress,” Canty said. “I was told she’s (Murray) only interested in helping large groups of people, not just one individual.”

Sochor wants Zeng to stay in the U.S. not only as an Olympic contender but as a coach. In a letter supporting Zeng’s citizenship, Sochor wrote, “As soon as he graduates, he will no longer be able to coach young athletes. I believe that if Colin was able to engage these young athletes full time, the United States development of future Olympians would be stronger.

“Here is where he learned to embrace his coaches and teachers instead of fear them. Here is where he learned to embrace religion. Here is where he learned that he can make people smile and share mutual respect with his peers. And here is where he should stay.”

It’s what Jolyn Canty wants more than anything for her Chinese-born son.

“This kid has gone through so much and he is so kind,” she said. “When he came to us he felt like he didn’t even deserve to live.”

“He’s a strong contender for the Olympics,” Sochor said. “I would like him to have that chance, but the most important thing is for him to be safe.”

As for Zeng, though he misses his parents and his sisters, he’s grown to love the country that has given him a chance to soar. While applying the discipline he learned as a child in China, it was here he discovered the joy of diving.

“There’s a lot of times I’m scared of the dive, but in overcoming the fear there’s such a joy when you do the dive,” he said. “If I can I would love to stay here the rest of my life.”

For that to happen, it’s going to take something with which this young man has become familiar.

“It’s going to take a miracle,” he said.