Idaho trying to help more students go on to college

“I really didn’t think I could go to college,” said Cathryn Coley while describing the help and guidance she received from the Near Peer program at Post Falls High School on Thursday, Feb. 25, 2016. She will be the first person in her family to attend college. (Kathy Plonka / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

In a state where less than half of high school graduates move immediately on to higher education, counseling hubs like this are the front lines of a desperate push to turn more teens toward college or career-training programs.

Cathryn Coley is one whose future changed when she walked through the door. The Post Falls senior plans to attend North Idaho College in the fall – something she didn’t consider possible just a few months ago.

“I didn’t even think I could go to college at first. I didn’t think there was anything out there for me,” said Coley, 18.

At the start of the school year she had just moved from Alabama, where the prospect of college seemed elusive. She and her mother would chat about it now and again, but “once we started talking about money, we’d get stuck and we’d eventually drop the conversation,” she said.

At Post Falls High, Coley found herself in a different academic environment.

“Grades, grades, grades – everyone was talking about college,” she said. “I’m like, OK, there’s no way I was going to make it.”

Then she spoke with the school’s Near Peer mentors: recent college grads hired to guide students to college or other postsecondary programs. They help kids explore career options and fields of study, and walk them through admission, financial aid and scholarship applications.

Coley applied for federal student aid and was awarded a Pell Grant to cover her first year at NIC. She also qualified for several scholarships.

“My mom cried,” she said. “She was so excited. No one in the family has gone to college. I’m the first one.”

Wide gap in educated workforce

In 2014, about 63 percent of American high school graduates were enrolled in college in the fall.

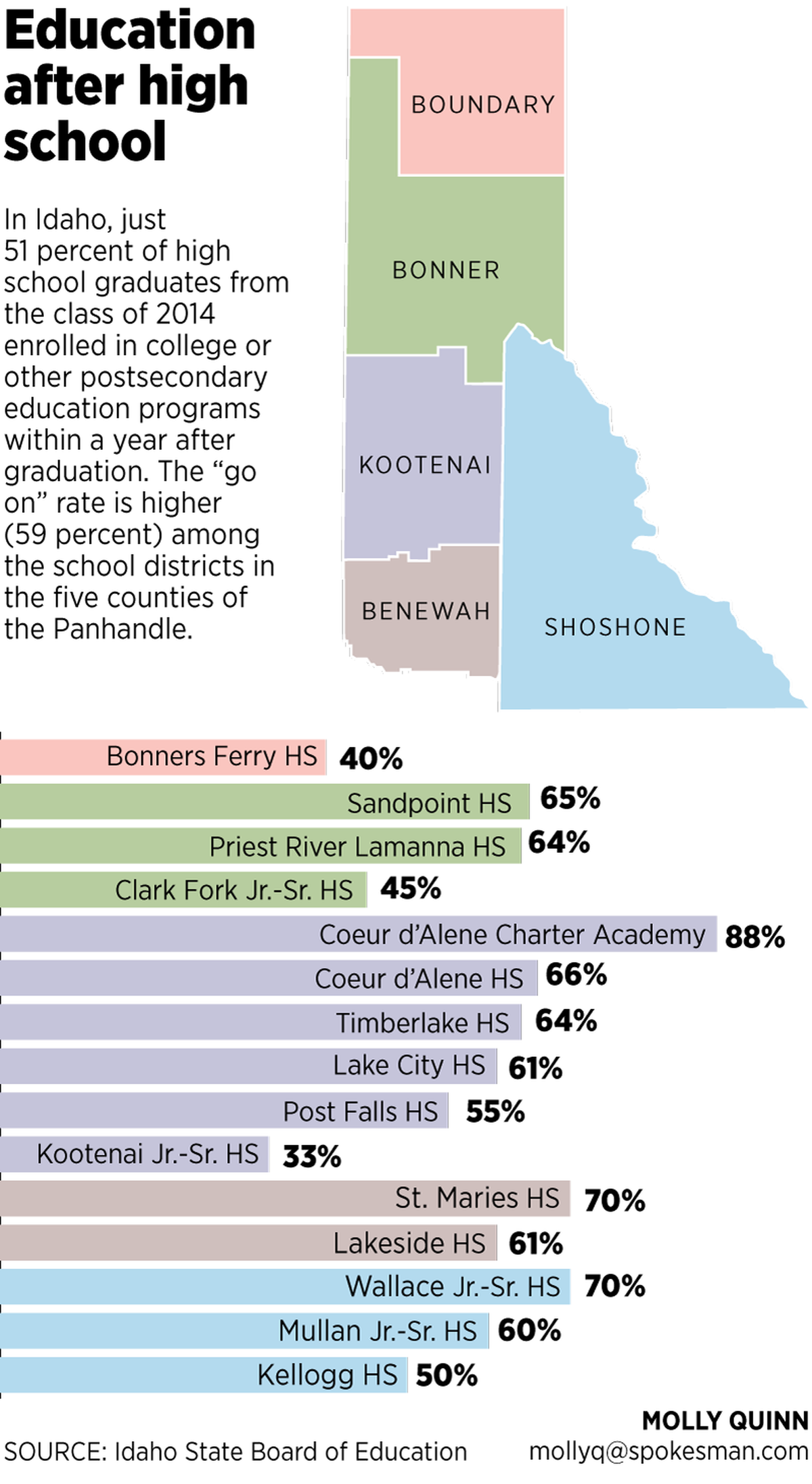

But for years Idaho has ranked at or near the bottom of all 50 states in sending students on to postsecondary education. From the class of 2014, just 47 percent were in college that fall. The rate rose to 52 percent within 12 months after high school.

The “go-on” rate in Idaho fell from 2012 to 2014 – a discouraging trend for state education leaders under pressure to prepare students for the demands of an evolving workforce.

“We’re not where we want to be,” said Blake Youde, spokesman for the Idaho State Board of Education.

In 2010, state officials set an ambitious goal: By 2020, 60 percent of residents ages 25 to 34 would have a postsecondary degree or certificate. But with four years left to go, only 40 percent of people in that age range meet the educational benchmark.

And studies indicate that within the next few years, close to 70 percent of the workforce will need to complete college or other professional training programs to be employable, Youde said.

“What we hear now is urgency,” he said. “It’s not employers running away from our state or saying Idaho is not a good place to do business. I think on the contrary they think it’s a great place to do business, and they are impressing upon us the need to help them here with the workforce.”

Why aren’t more Idaho students heeding the call to higher education?

Family influence is a big reason.

“Idaho traditionally has not had a high go-on rate, so now it becomes a generational issue,” Youde said. “You know, ‘My parents didn’t go and they both got jobs, therefore I don’t need to go and I can still get a job.’ ”

Byron Yankey, who also works at the state Board of Education, manages the College Access Challenge Grant in Idaho. The federally funded project helps low-income students prepare to enter and succeed in postsecondary education.

“The number of first-generation (college) students is very, very high across the state of Idaho,” Yankey said.

Religion also plays a role in Idaho’s low rate of immediate transition to college. About a quarter of the state’s residents belong to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and high school graduates from Mormon families traditionally serve as missionaries for up to two years.

And those who enter military service out of high school are not captured in the go-on rate, even if they receive training that can lead to a career.

Financial constraints also keep many students from moving on. Most young people know they can boost their lifetime earning power with a college degree or professional certificate, but they still get lured by the short-term gain of entering the job market right after high school.

Young men especially are tempted to forgo college for an immediate wage, Youde said. And when the economy is improving, college enrollment dips all around as hiring picks up, he said.

Graduates who postpone college plans are at greater risk of never enrolling. “The more years they’re out of high school, the less likely they are to go,” Youde said.

Idaho is a big state with institutions of higher education concentrated in a few population centers. Moving away from home to attend college or vocational school is a financial and social obstacle for quite a few teens.

“Many of our students … are site-bound, meaning that they typically do not move far away from their hometown or their families,” Yankey said.

Idaho boosting high school advising programs

Idaho is trying to smooth the path to higher education with measures to simplify how to prepare, enroll and pay for it.

One initiative, Direct Admissions, gives high school seniors a jump on being admitted to the state’s public colleges or universities. In November, students receive letters telling them which of the schools have pre-accepted them based on their grades and college entrance exam scores.

The Opportunity Scholarship provides resident students up to $3,000 a year for costs not covered by grants and scholarships at any of Idaho’s eight public and three private colleges and universities.

The state set up a one-stop shop, at nextsteps.idaho.gov, for making the leap to college. The website walks families through the whole process from as early as the eighth grade. It includes tips on taking dual enrollment and Advanced Placement classes, preparing for the SAT or ACT exams, and navigating the labyrinth to grants, scholarships and loans.

These efforts are encouraging, Youde said.

“They’re definitely showing us that there’s a reason to expect increasing go-on rates,” he said. “We still have a ways to go.”

Idaho also has funded pilot projects to strengthen high school college and career-advising programs. Lawmakers this year voted to have school districts report on the impact of these programs, and Gov. Butch Otter recommended spending $5 million to expand college and career advising across the state. The House and Senate approved those funds as part of the K-12 budget.

That money would enable high schools to set up programs like Near Peer, using young adults to advise and mentor students.

‘Summer melt’ shrinks college-bound pool

Sandpoint High School employs a Near Peer mentor to work alongside Jeralyn Mire, the postsecondary transition counselor. While other school counselors focus on graduation requirements and other issues, Mire is all about where students go after high school.

“We’ve been at this for eight years,” she said.

Each year, the school surveys its graduating seniors about their plans. Between 75 and 80 percent say they intend to enroll in a two-year or four-year college, pursue technical training or join the military. But not all are able to follow through.

“We call it the summer melt,” Mire said. “They’ve applied, they’ve been accepted, they’ve completed their (financial aid application), and something happens over the summer. They just don’t get there.”

And so the school’s go-on rate drops to 60 to 65 percent – still better than the state average, but not as high as Mire would like to see. And she knows that some of these students abandon their college plans over minor bumps in the road.

Mire has worked with students who find the financial aid procedure too stressful and frustrating. “It was so complicated … they just gave up,” she said.

Others lack support at home and are too intimidated to reach out for help, she said. “There’s a lot of help at the college level, but I think they don’t know who to turn to, and they don’t know how to advocate for themselves.”

Making it fun, less stressful

Post Falls High School is in its fourth year of using two full-time Near Peer mentors. They meet one-on-one with students, including all juniors and seniors, about college and career plans.

Their room halfway down a second-floor corridor is casual and inviting, with floor bowling, a minifridge for snacks and a microwave. Students kick back on a sofa as if they were lounging inside a dorm.

They call the mentors by their first names, and they can win gift cards and raffle prizes for dropping in and completing tasks along their journey to college or career training.

“We try to keep it low-key, low-stress, kind of fun – so they’re not afraid to come in,” said one of the mentors, Tiffany Beebe, who has a bachelor’s degree from the College of Idaho in Caldwell and a master’s from King’s College London.

The program is making a difference.

“Our high school’s go-on rate is increasing steadily each year, compared to the state average,” Beebe said.

Some students need help as they plow through a tedious online application, and the counseling office isn’t staffed for that level of individual attention.

“With 1,500 students and four counselors, they just don’t have the time to do that with every single senior,” Beebe said.

The teens who walk into the Near Peer room often have an idea for a career path but don’t know which school or major will get them there.

“So we start them on their research, figuring out what they want out of their college experience, what will make them happy and successful, where they see themselves,” Beebe said.

Last year, 61 percent of Post Falls seniors completed the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, which determines grants, work study and loan amounts, as well as how much a family is expected to contribute to college costs.

It can be an intimidating exercise.

“They’re afraid of the costs,” Beebe said. “We still encourage them to apply just to see what they’re offered. A lot of them don’t know what’s available and are surprised when they see they qualify for the Pell Grant or need-based scholarships.”

Those scholarship wins are announced on the wall outside the door of the Near Peer room, along with a map showing where seniors are headed after high school. It’s an effective marketing device.

“Other students walking through the hallway are seeing that map, so they know these students are going somewhere,” said Katalina Chacon, the school’s other Near Peer mentor and an Eastern Washington University graduate.

CdA high schools awarded

At the start of a packed assembly inside the Coeur d’Alene High School gymnasium last month, students and teachers listened to several speakers laud the school’s academic achievements: A graduation rate of 93 percent. SAT participation up 68 percent in the past three years. Two-thirds of AP students earning college credit and placement.

“So for being so deviant, abnormal and unusual, give yourselves a round of applause,” said Barbara Cronan with The College Board, a national nonprofit group that promotes college readiness and admissions.

Cronan was in town to present both Coeur d’Alene and Lake City high schools the 2015 Gaston Caperton Opportunity Award and a $25,000 prize. Only two other high schools in the nation were given the honor, which celebrates rigorous academic offerings and innovative college-prep programs, especially to help underrepresented students.

Coeur d’Alene Public Schools has worked to create a school culture where students early on are exposed to the importance of college or other educational opportunities after high school, Coeur d’Alene Superintendent Matt Handelman said.

“We start with the premise that every student, regardless of his or her life circumstances, should and will be given the tools and opportunities … to enable them to pursue and realize a dream of going to college,” Handelman said.

Teachers and staff are encouraged to wear or display their college colors. Career exploration begins in middle school. And all students in grades 9 through 11 take the PSAT, a preliminary version of the SAT.

Coeur d’Alene Public Schools has the highest composite SAT scores of the 10 largest school districts in Idaho.

And since 2010, the district has doubled the number of Advanced Placement Program courses, while the two high schools have almost tripled their AP participation rates. The schools also have seen steady growth in dual enrollment through NIC and the University of Idaho.

Unlike many parts of Idaho, high school graduates from Kootenai County have a lot of higher ed options in the Coeur d’Alene-Spokane region.

“We’re lucky, we’ve got a lot of good access,” said Shannon Gabby, the counselor for this year’s senior class at Lake City High School.

Gabby estimates that about a third of the school’s 306 seniors have been locked onto the college path since childhood, and another third are considering some type of postsecondary education.

“I believe every kid should have the opportunity, but is it realistic for every student?” she said.

“We’ve got to send that message to kids, that they are individuals,” Gabby continued. “Everybody has a strength; everybody has something to contribute.”

First in family to go

On a recent Monday at Sandpoint High, Jeralyn Mire pulls two seniors into her office who she said demonstrate the drive and independence of motivated, college-bound students.

BreLynn Converse, 19, is headed to North Idaho College this fall and hopes to study business and secondary education. She was preapproved on grades alone to attend any of Idaho’s colleges.

A resident of Laclede, just down the Pend Oreille River, Converse would be the first in her family to complete college.

“My parents definitely pushed me,” she said. “They want me to have a life that they never got.”

She also credits Mire for being so available. Without the counselor’s help, “it would be so hectic,” Converse said. “I would be scrambling, I wouldn’t know what to do.”

Mire said Converse has shown tenacity in tackling her college and financial aid forms.

“Those kinds of skills are what’s going to help her be great in college,” she said. “She won’t give up.”

Paul Sundquist, 18, who lives in nearby Kootenai, is headed to Montana Tech in Butte on academic and football scholarships. He’s enrolling in the applied health program and is considering several fields of study.

Sundquist said his parents didn’t attend college but strongly encouraged him and his older sister to go.

“They both understand how much our economy is changing, our society is changing, that you need that degree just to be comfortable,” he said.

The value of postsecondary education also was emphasized at every level of high school, Sundquist said. “They just consistently promote it, from freshman year to senior year.”

When he got stuck, he’d pop into Mire’s office. “I would come in here a lot, just to ask questions and have Jeralyn help me,” he said.

“He’s been willing to say, ‘Hey, I need help with this.’ He’s doing a great job advocating for himself,” Mire said.

‘Gap year’ gamble

Other students have college in their sights but first want to take a break to find their focus or put some money in their pockets.

That’s what Coeur d’Alene friends Nikki Rossman and Dani Brown have in mind. The Lake City High School seniors want to start at NIC and finish at the University of Idaho, but they will take a “gap year” to work and do a little travel together, possibly visiting Italy and England.

“I’m trying to find my passion and figure out what I want to do with my life,” said Rossman, 18. The year off, she said, will allow her to “find my bearings, try to assert myself as an adult in the world.”

She’s leaning toward technology studies but doesn’t want to waste time and money being indecisive with a major, she said.

Brown, 17, knows what career she wants to pursue – teaching high school English – but she needs to work and save up first.

“I’m doing it for the money to help with college and make it a little easier,” she said.

The two sought out others who have taken a year off to ask about the pros and cons.

“A lot of them said that it was a good opportunity to be adjusted to adult life before you throw yourself into school life as well,” Brown said.

Still, the decision was difficult, Rossman said, especially as she saw other friends firm up plans for after graduation.

“I’m a little jealous that they know what they’re going to do,” she said. “There is a pressure there. To not know what I want to do is a little scary.”

Her family was concerned she might not stay motivated to enroll after taking the time off.

“They’ve warmed up to the idea,” Rossman said. “I want to go to college.”